In Northern Libya, a battle is unfolding for the city of Sirte, the key center of the so-called oil crescent. From the south, news is arriving about the struggle for El Sharara – the country’s largest oil field. Libyan oil, the export of which was nearly halted entirely in January-February, is once again in the headlines. However, who actually owns Libya’s black gold? What players’ interests intersect in the struggle for this resource?

Reserves, production and export

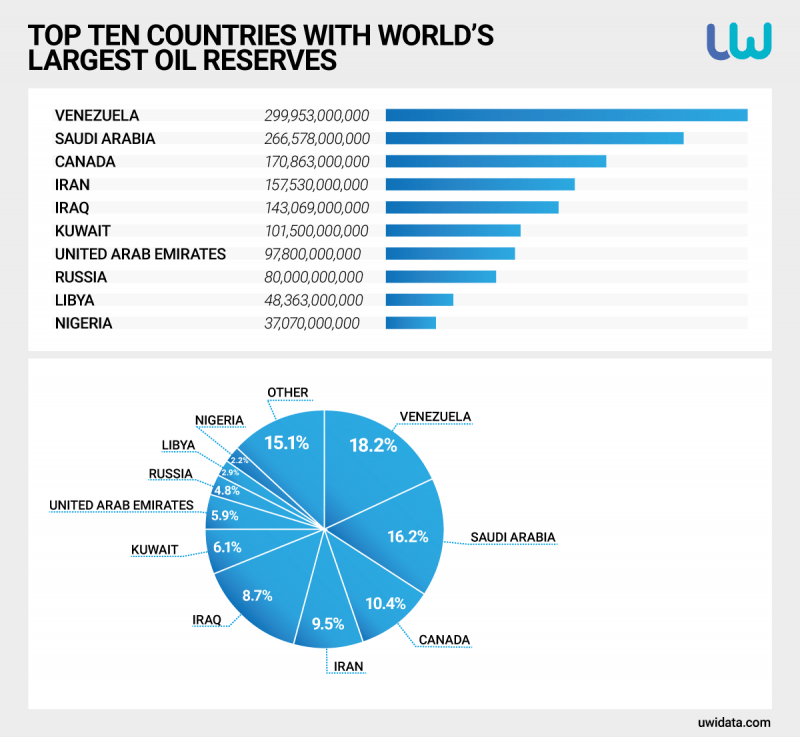

Libya is one of the most important oil-producing countries in the world. According to OPEC estimates, the oil and gas sector accounts for 60% of the country’s GDP. Some experts suppose the higher figure – 80%. In terms of oil reserves, the country is among the 10 largest in the world with – 48,363 million barrels. In 2018, according to OPEC, the volume of oil production was 951.2 thousand barrels per day. In January 2020, it was in the order of the 1.3 million barrels per day.

Libya’s largest oil fields

80% of Libya’s oil production comes from the Sirte basin, the “oil crescent” in the Gulf of Sirte. There are 4 large oil terminals in this area – Es Sider, Ras Lanuf, Marsa el Brega and Zueitina. In the west of Libya there is a large terminal in the port of Zawiya, terminal Melitah, as well as two terminals associated with fields on the Mediterranean Sea shelf – Al Jurf and Bouri. In the east of the country, the Marsa el Hariga terminal is located in the port of Tobruk.

The largest amount of oil, before the work of terminals was stopped, had been pumped through the Es Sider – 250 thousand barrels per day, located east of the city of Sirte.

The second place was taken by Zawiya, which exported 240 thousand barrels a day from the El-Sharara field in south-western Libya. It produced 300,000 barrels per day.

In the third place, another port from the oil crescent, Ras Lanuf, transferred 220,000 barrels per day. Fourth, Marsa el Hariga – 120,000 barrels per day.

The largest oil fields outside the oil crescent are El Sharara (300,000 barrels per day) and El-Feel (Elephant) (70,000 bpd). To the east: Sarir/Mesla (155,000 b/d).

According to their five-year plan, the Libyan National Oil Company (NOC) expects to raise production to 2 million bpd by 2022 and 2.2 million bpd by 2024. This would require $15 billion of infrastructure investment. Even then, however, the country will not reach the 1969 level of 3.1 million bpd. Earlier representatives of the Libyan oil industry estimated the highest potential level of oil production in Libya at 5 million bpd.

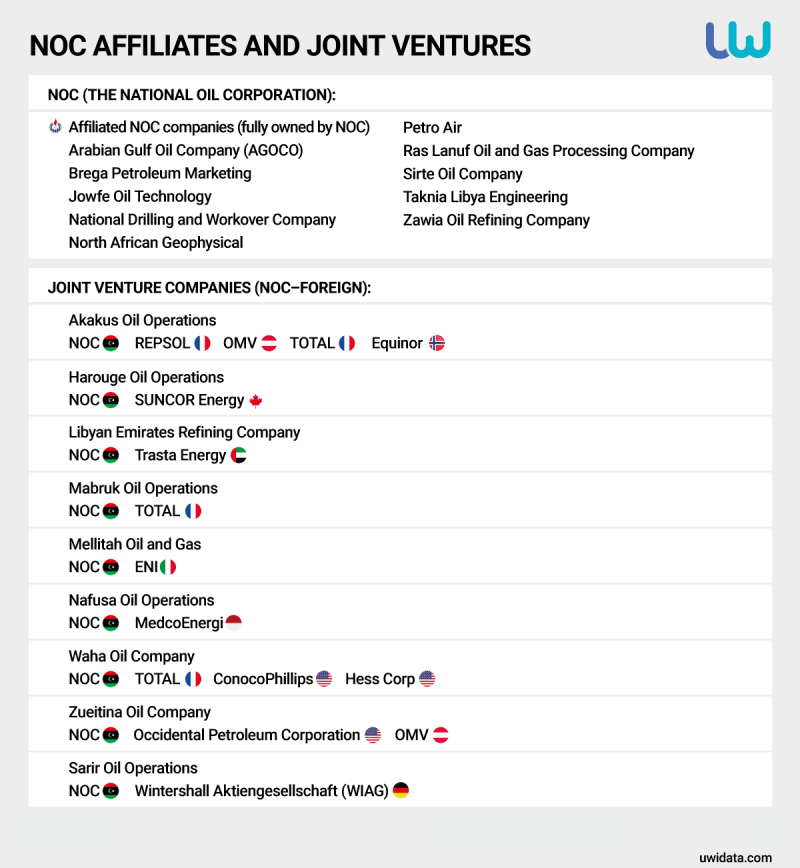

The NOC is a state-owned company, which has the sole right to sell Libyan oil abroad, but due to the absence of a state in Libya, it is in fact a separate political entity, which has complex relationships with foreign investors, the governments in Tripoli and Tobruk. There are also local companies in Libya that are formally subordinate to the NOC, but which have a high degree of autonomy, and are in complex relationships with municipalities and tribes where oil production is taking place.

Although the NOC’s mandate is from the Tripoli based Government of National Accord (GNA), there are direct supporters of the rival Libyan National Army (LNA) on the board who have previously expressed direct support for general Khalifa Haftar’s actions. Recently, however, they have refrained from making any statements on the Libyan conflict.

The conflict between the NOC and the East

In January-February, protests by local tribes and pressure groups affiliated with Libyan National Army Commander Khalifa Haftar resulted in an almost complete halt to oil sales. Libya’s oil exports came only from fields controlled by the forces loyal to the Government. These are Al Jurf and Bouri – offshore fields. Eventually, oil exports fell to 90,000 bpd.

More than 1 billion barrels of oil per day have not been added to the world oil market. However, the reduction of oil consumption due to the coronavirus crisis led to the fact that the extraordinary situation in Libya had a generally insignificant impact on the world oil markets.

Half of the oil went to the Mediterranean markets (Italy, Spain and France). One fifth went to China.

Reasons for blocking oil exports were both political and economic. For Haftar and the government of eastern Libya, it was and is a means of pressure on the GNA. For the tribes and municipalities allied to them, it is a desire to redistribute revenues. The only structure that could sell oil for export was the NOC, headquartered in Tripoli. The money from the proceeds was also distributed through Tripoli and the Central bank of Libya, based here, which was not to the liking of locals and representatives of southern and eastern Libya.

Equitable distribution of oil revenues in the regions of Kirenaika, Tripolitania and Fezzan is one of the key points of the political project presented in April 2020 by Aguila Saleh, Speaker of the House of Representatives (HoR) in Tobruk, which is the only legitimate state institute, that endorses Haftar.

The LNA and the Libyan Provisional Government in Tobruk (civil administration loyal to LNA) have been in conflict with the NOC for years. One of their main demands is to move the NOC headquarters to Benghazi. There the government of eastern Libya has organized an alternative NOC, but it was not possible to formally conduct trade operations through it.

In early June, the NOC announced the start of oil production at El-Sharara and El-Feel fields. By 10 June, however, production at both fields had been suspended by groups of armed men allegedly subordinate to the LNA.

Foreign interests

Although only the NOC may formally sell oil abroad, foreign companies have been involved in Libyan oil production since Muammar Gaddafi. As a rule, they hold a significant percentage in some or other fields in Libya. Foreign companies are present in Libya’s oil production under the Exploration and Production Sharing Agreements (EPSA).

The field is usually managed by local companies, which are subsidiary companies of the NOC. Some of them are joint ventures with foreign investors. For example, Akakus Oil Operations (AOO), operating in the south of the country, was originally a subsidiary of the Spanish oil and gas company Repsol and later became a joint company of NOC, REPSOL, OMV and TOTAL.

Italy

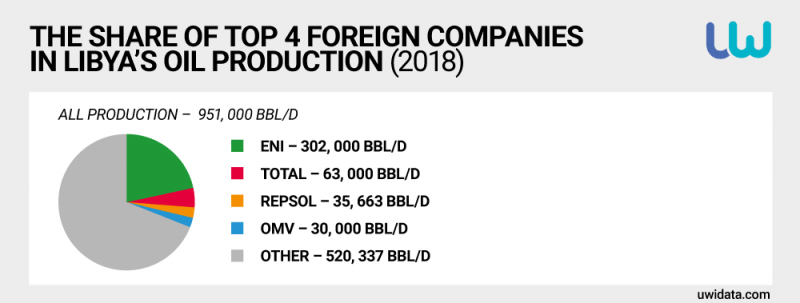

The Italian oil and gas giant ENI, considered to be the largest foreign player in the Libyan oil market.

In 2019, ENI’s annual production of oil and gas condensate in Libya was 37 million barrels.

In 2017 ENI produced 384,000 barrels per day in Libya, the highest level in the country, but in two recent years the production has decreased.

In 2018 Eni production in Libya amounted to 302, 000 barrels per day, and in 2019 – 291, 000 barrels per day. ENI has 11 licenses for oil production in Libya.

ENI is developing the Bu-Attifel oil field (oil crescent), El Feel (working interest of Eni is 33.3%) and the Wafa field in Fezzan. Offshore, these are the Bouri oil field and the Bahr Essalam gas condensate field in Tripolitania.

The company, representing the former colonial metropolis, acquired half of BP’s oil and gas assets in Libya in 2018 and has been actively expanding its presence in Libya in recent years.

The parties agreed to work towards Eni acquiring a 42.5% interest in the BP-operated exploration and production sharing agreement (EPSA) in Libya. On completion, Eni would also become operator of the EPSA. In 2018 BP held an 85% working interest in the EPSA, with the Libyan Investment Authority holding the remaining 15%.

Mellitah Oil and Gas, a joint venture between ENI (50%) and NOC, is among the companies in which ENI has a significant stake.

It should also be borne in mind that ENI produces most of the gas in Libya, which is transported to Italy via the Green Stream pipeline (8 billion cubic metres per year).

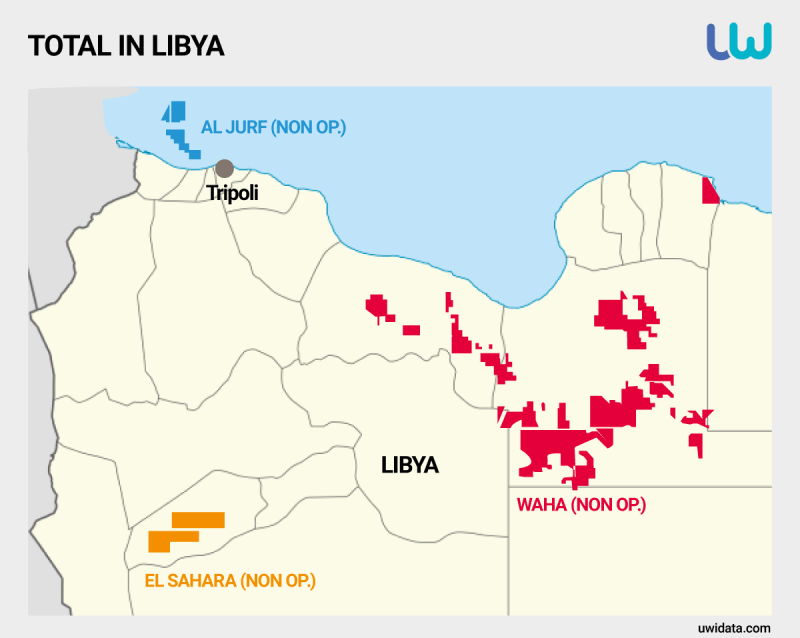

France

The French gas giant Total only produced 31,000 barrels per day in 2017. In 2018, it was 63,000 barrels per day.

According to the company’s website, it owns 75% interest in the offshore blocks 15, 16 and 32 Al Jurf, which are not in operation, in western Libya, and 16.33% of the shares in the concessions Waha (Sirte Basin). In December 2019, Total acquired a stake in the US company Marathon Oil in Waha.

Total’s website notes that the agreement was approved by the Government of Libya (not explained what Government). At the same time, the transfer of the stake to Total passed after the seizure of the oil field by LNA.

Total also owns a significant share of El Sharara blocks 129/130 (30%) and 130/131 (24%).

The Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC) is developing this field in agreement with Repsol (Spain), Total (France), OMV (Austria) and Equinor (Norway).

The United States

The only American company with a major stake in today’s Libyan oil industry is ConocoPhillips. It holds 16.33% of Waha concessions (a subsidiary of NOC – Waha Oil Co).

The US oil company’s position on the stock market has seriously declined due to problems in Libya (oil export stops).

There are also other US companies that have joint ventures with NOC – Hess Corp and Occidental Petroleum.

The giant of American oil industry Exxon Mobil is not present in Libya, despite it being there in the Gaddafi era. Exxon Mobil left the country in 2014.

Spain

The average production volume of Spanish oil company Repsol Spain in Libya in 2017 was the equivalent of 25,400 barrels per day. According to the latest figures for the year Repsol produced 11 million barrels per year and 35,663 bbl/d in 2018.

The Repsol website reports that the Spanish company is currently actively developing the Sharara NC-186 oil field in Murzuq basin (32% stake). Neighboring NC 115 is also in the Repsol area of interest.

Austria

OMV Austria’s production in Libya averaged 25,000 barrels per day in 2017, and 30 kboe/d in 2018. Average production in Libya was 16 kboe/d in Q1/19, compared to an average of around 35 kboe/d in the remaining quarters.

According to the company’s statements, it could rise to 40,000 barrels per day if the political situation improves. El-Sharara, already mentioned, is a field where OMV is present.

Also OMV, according to the company’s website, “is currently the sole international partner of Libya’s state-owned National Oil Company (NOC) in the Nafoora Aguila oil field, located in the Sirte Basin in the east of Libya. Other areas where OMV operates include the Sirte, Murzuq, Ghadames, Cyrenaica, Kufra and Pelagian Basins.’’

Germany

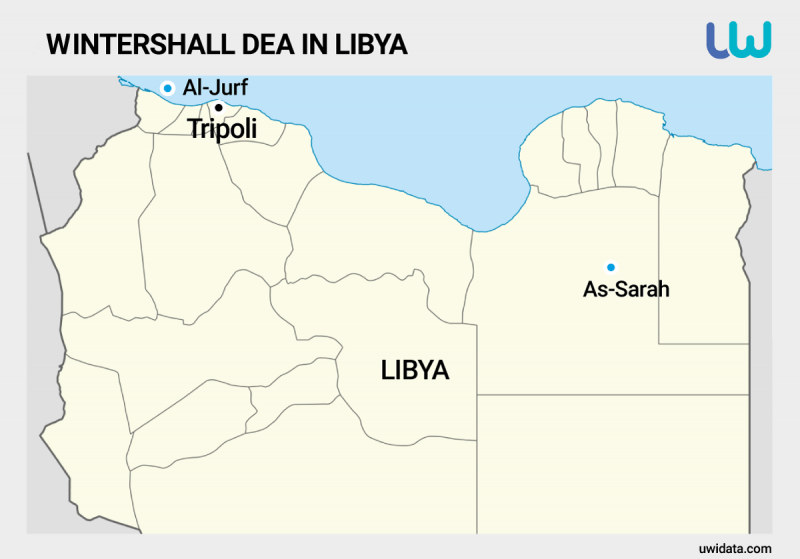

Germany’s largest oil and gas company, Wintershall Dea, is also present in Libya. Wintershall Aktiengesellschaft (WIAG), a subsidiary of Wintershall Dea, has been developing two fields in the East Sirte basin (sections 91 and 107). Since 2008 Gazprom E&P International has held a 49% share in Wintershall Aktiengesellschaft (WIAG).

For a long time, WIAG solely exploited these fields. In 2020 WIAG plans to transfer management of these fields to Sarir Oil Operations – its joint company with NOC. This was preceded by a dispute with the NOC with WIAG, when the Libyan company imposed on Wintershall Aktiengesellschaft to take over management of these fields.

Wintershall Dea has a stake in Al-Jurf and 3 oil fields in Cyrenaica and the Sirte basin, but has not been operating since 2014.

Countries, that are interests in strengthening their presence:

Russia

Among Russian companies, Rosneft, Tatneft and Gazprom considered the possibility of investing in the Libyan oil industry. In 2017, the head of NOC met with the top management of the company Tatneft (Russia) and urged the company to resume exploration in Ghadames and Sirte.

In December, NOC stated that Tatneft has resumed exploration work in the Ghadames Basin in the Hamada region in western Libya (GNA control zone).

It should be noted that the assets of WIAG, which is co-owned by Gazprom, are in the east (under Haftar’s control). The areas are controlled by local Salafis of the Subul al-Salam Brigade.

The United Kingdom

British BP does not show much interest in Libya except for the BP-Eni deal. Royal Dutch Shell is not active in the country after the 2011 coup.

US

In January 2020, Al-Monitor, citing FARA’s data on foreign lobbying activity, reported that lobbyists from the self-proclaimed Libyan National Army met with Republican legislators and US officials responsible for energy policy in the summer of 2019. LNA commander Khalifa Haftar also met with a number of high-ranking Americans (US Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland and Brig. Gen. Steven deMilliano of US Africa Command).

The delegation also included Matthew Zais, the principal deputy assistant secretary of the Energy Department’s Office of International Affairs.

The US Department of Energy then published photos from the meeting, noting that it was interested in Libya’s competitive energy sector and in countering Russian influence.

@DOEIntlAffairs joined @WHNSC, @USAEmbassyLibya, & @USAfricaCommand for a dialogue with LNA's Khalifa Haftar on achieving a secure and prosperous #Libya. @Energy encouraged a competitive and transparent Libyan energy sector for all Libyans, and wary of malign Russian influence. pic.twitter.com/EZ593kZsbe

— DOE International Affairs (@DoeIntlAffairs) November 26, 2019

As Matthew Zais wrote “The US looks to partner with Libya to ensure it emerges from civil conflict able to effectively administer Libyan energy resources for the benefit of all Libyans”.

https://twitter.com/MatthewZais/status/1199153697751732225

The US’ interest in Libya’s oil fields is also reflected in the approval of a document by the Congressional Research Service “Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy from April 13, 2020, that “«Libya’s natural resources and economic potential may provide future opportunities for strengthening U.S.-Libyan trade and investment ties”.

Turkey

Turkey has repeatedly expressed its desire to start exploration on the Libyan shelf, after signing on in November 2019.

In May, Turkish Petroleum, the day before, turned to the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNC) in Tripoli to start exploring oil and gas fields off the Libyan coast.

On June 8, Turkey plans to conduct exploration work on seven prospective sites in Libya, Energy and Natural Resources Minister Fatih Donmez said.

Average daily oil consumption in Turkey is 1 million barrels, so that Libyan resources will be enough to meet the needs of the country, En Son Haber wrote.

The UAE

The world media have repeatedly reported on the UAE’s intention to trade in Libyan oil bypassing the NOC in Tripoli. Such information was reported by the Wall Street Journal in 2018.

In May, a French frigate stopped a tanker, which was illegally transporting oil from eastern Libya. Initially, Bloomberg reported that the oil was coming from a company registered in the UAE. However, this information then disappeared from the site (although it remained at the news address).

NOC in 2018 said it won a court case with two foreign companies, Trasta Energy (Emirates) and Libyan Emirates Refining Company (Lerco). In 2013, Trasta and Lerco have initiated arbitration proceedings against the NOC in

The International Chamber of Commerce, stating that the NOC failed to protect the Emirates’ investment. The court, however, ruled in favour of NOC b, awarding NOC compensation for counterclaims totalling $116 million.

LERCO is a joint venture between NOC and Trasta, which operates the Ras Lanuf refinery.

Obviously, the UAE has interests in the Libyan oil sector, although there are no serious assets except for Ras Lanuf.

Intra-Libya structures and oil

Libyan oil companies, subordinated to the NOC seek the best possible cooperation with the various political and military forces competing for control. However in these specific circumstances they may act independently from NOC. For example, in 2011 one of largest NOC subsidiaries The Arabian Gulf Oil Company (AGOCO) with HQ in Benghazi used oil money to finance an anti-government uprising.

In April 2019 AGOCO supported Haftar’s offencive on Tripoli, hailing “On the success and progress in its striving against extremist terrorist militias and militias which steal public funds’’. Another NOC subsidiary Sirte Oil Co also praised Haftar.

One of the most interesting phenomena is The Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG). This structure was established in 2012 at the request of the NOC. However, in the general chaos PFG quickly became a structure that began to seize oil fields, changing the side of the conflict and engaging in oil smuggling.

In March 2014, the US Navy intercepted an oil tanker flying the North Korean flag, which sailed from Sydra with 230,000 barrels of oil, then the port was controlled by PFG under the command of Ibrahim Jadran.

There are now at least 2 PFGs. The PFGs loyal to the LPA are led by Naji al-Moghrabi, Major General of the LPA. His forces participated in the oil blockade in January-February.

The GNA’s Ministry of Defense has its own PFGs – they are commanded by Brigadier General Ali Al-Deeb. These PFGs resumed production at the El Sharara and El Feel fields in early June 2020. However, almost immediately the forces of Colonel (according to other sources of Brigadier General) Muhammad Khalifa, who is subordinate to the LNA, arrived from the city of Sebha and stopped oil production.

The most complicated intertwining of tribal, ethnic and clan interests is in the south of Libya.

In 2014-2015, the Tuaregs and Tubu peoples were in conflict over control of the city of Ubari and the surrounding oil fields. The conflict was extinguished through the mediation of Qatar. However, experts note the rivalry between ethnic and tribal groups for oil smuggling routes to Chad, Mali and Niger, where the same Tuaregs and Tubus live.

An oil pipeline leading from El Sharara in southwestern Libya passes the city of Zintan. The Zintan militia is currently loyal to the GNA. They have previously captured Al-Fil and Al-Shararah. It is possible that they may do the same in the future. However, some Zintans (Zintan Salafis, whose spiritual leader is Abu Khattab Tarek Darman) are fighting for the LNA.

In addition, the Fezzan Rage is active in the Libyan south. It is a group of young militant activists from the south, mainly from the town of Ghat on the border with Algeria. It has a strong position as a former Cadafist. They blocked Sharara and El Phil twice in December 2018 and January 2020. Engaged with both Sarrage and Haftar.

In western Libya, the problem is the control of the Muslim Brotherhood over the entire economy, including oil.

Conclusions:

– The situation in Libya’s oil industry is extremely complex and unpredictable.

– Any company coming to Libya must take into account its complex mosaic of interests, instability and influence of both local companies and governments, as well as those of ethnic groups and militias that struggle among themselves to control the fields.

– The main players in the market are Italy and France (ENI and Total).

– Other countries are interested in Libyan oil, including Turkey, Russia, UAE and the United States.

– Turkey is primarily interested in oil on the coast. Russian companies are interested in oil on the continent. In this respect, their interests do not yet contradict each other.

– The key factor that can ensure stable functioning in Libya is security. Those who will ensure security will be able to crowd out their competitors.

– The most acceptable option for news companies would be to restore state unity.

– Those companies that are already present in Libya are gradually learning to operate in areas where there is no state authority. This experience can be perceived as their advantage compared to the competitors. It is unlikely that they will wish to be on a par with the others, if by some miracle a stable state emerges.

Leave a Reply