The history of the United States (US) strategic deployment in Latin America is extensive. Since the so-called Monroe Doctrine (1823, there has been no cessation in Washington’s interference throughout the southern half of the hemisphere in various ways. By the end of World War II, a global liberal order began to form and the world was divided into two poles led by the US and the USSR respectively. These two forces engaged in a multidimensional dispute on a global scale, creating a balance of power where all other states served as satellites, proxies or formed the so-called Third World. The end of the USSR resulted in an era of unipolarity which still persists to the present. During this era, neoliberalism expanded throughout the world and the US became the Sole Superpower, hegemonizing power and exporting American social values and ideology. Throughout the 20th century, Latin America provided vital sustenance for the hegemon.

Of course, in the Middle East and Asian Pacific, the US has a massive presence which exceeds, in material terms and global impact, its presence in Latin America, especially in terms of its military footprint, confrontations and direct investment. Nonetheless, Latin America is a territory where sophisticated strategies have been devised and implemented, making this continent a lynchpin to the US hegemony formation and, therefore, vital in its rivalry with other world powers. After World War II, the US began a massive continental offensive that overdetermined the destinies in numerous American nations, installed social policies, influenced or shaped actual (or potential) economies and dominated diplomatic processes.

Military/civilian “puppet” governments were installed in countries where rebellions and opposition movements grew or achieved victory. In establishing its domination over the region, Colombia turned to be one of the US’ closest allies and the base of a colossal and unique counterinsurgency effort– however, this was not achieved without heavy resistance. In this article we will address the relationship between the US and Colombia, a situation which has left 450,000 people dead in armed conflicts between 1948 and 2018.

THE BURDEN OF HISTORY

While we cannot be sure what Colombia would look like today if the US had not gotten involved, It is safe to say that an oligarchic bloc has consolidated itself in power since it did, resulting in one anti-popular repressive government after another, all of which used heavy-handed and persistent measures to secure the power and wealth a small circle of families. This resulted in large masses of dispossessed, displaced, landless, poor and marginalized people with countless unfulfilled demands in a democracy that has had 5 progressive presidential candidates assassinated since the beginning of the second half of the 20th century.

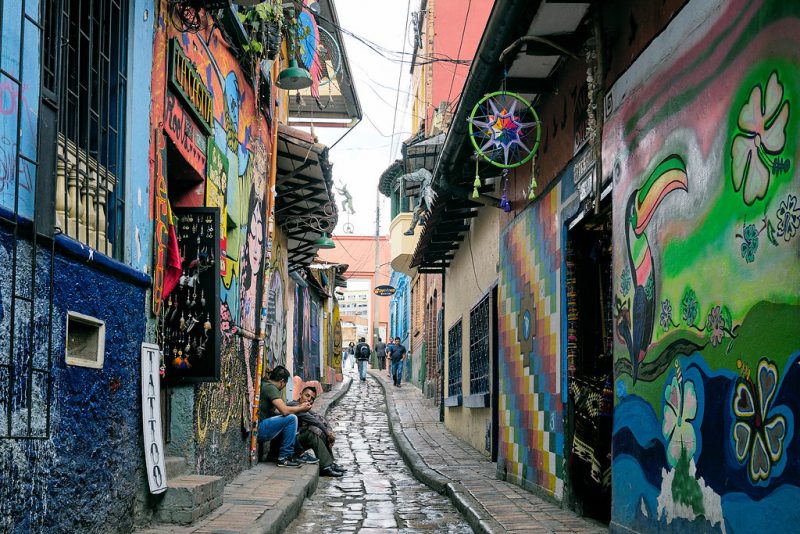

The first was Jorge Eliécer Gaitán (April 9, 1948), a mass leader and professional politician with enormous popular support who had projected himself to be the next president, making the foundations of the economic and political regime tremble. At that time, similar leaders emerged in Latin America, most of whom came from the military. Gaitán, however, was a civilian. In the eyes of the local oligarchy and American imperialism, that was even more dangerous. On the day of his assassination, the world witnessed the so-called “Bogotazo”, a massive and violent uprising, a chaotic response by masses of people to the killing of their leader which symbolized the annihilation of their hopes. This resulted in popular defeat and thousands of deaths. The oligarchic rule and the landowner model only deepened as a result.

From that point on a civil war, formally called “La Violencia” (1948–1958/64), began, during which fights between the main parties (Conservative and Liberal) left more than 200,000 people dead, most of them from poor rural communities.

Flickr

At that time, the so-called National Security Doctrine (the installation of military dictatorships trained at the US Army School of the Americas) was implemented in order to sustain or restore order in the face of rising and powerful revolts and revolutions.

Starting in the 1950s, Colombian low and middle class peasants and farmers organized themselves as “independent republics” based in Marquetalia (Tolima) and grew outside the control of the state. Denounced by the government as communist communities that threatened national security, Colombian Army and paramilitary groups persecuted the insurgent. But they resisted. As a part of US President John F. Kennedy’s anti-communist LASO plan (Latin American Security Operation), the US engaged Operation Marquetalia on May 18, 1964, the largest counterinsurgency operation ever carried out in Latin America: 1,000 soldiers under US leadership landed in the area. Whole communities were bombed and besieged. A large number were killed and entire families starved. Survivors managed to break the military siege, took refuge in Riochiquito and formed the South Bloc giving birth, in union with the Communist Party of Colombia, to the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla organization, with an all-time high of 20,000 fighters. Shortly after, other powerful guerrilla groups were also born (the ELN, National Liberation Army; M-19 etc.). The peaceful and democratic route had been violently closed again by the landowners and military.

IN THE BEGINNING, THE USAID WAS CREATED

In April 1961, the world witnessed the US first major military defeat in Latin America: the failure of the CIA invasion of Cuba at Playa Girón. Shortly thereafter, on November 3, the Alliance for Progress was officially launched, the US’ first strategic (anticommunist) plan with claims of continental leadership. Just one month later, JFK visited Bogotá and installed the Peace Corps and several other governmental organizations, including USAID (US Agency for International Development). Two weeks later, Cuba completed a Socialist Revolution and became a catalyst for a number of other national liberation struggles.

The relevance of these kinds of policies and their persistence over time set the tone for Colombia’s relations with the US. USAID Director General Mark Green recently visited Colombia (May 13, 2019) and announced a fresh $160 million assistance program for Colombian brand new government. President Iván Duque welcomed the money and the orientation it entailed. He said the funds would primarily be used in productivity projects involving former FARC militants and for improving security and state presence in isolated regions where FARC and other guerrillas were present. Green underlined the tenor of the relationship between both nations: “It’s worth celebrating because we’re much more than mere partners, we’re close neighbors and true friends…There is an unshakable bond between our two nations…This special relationship has grown throughout the years as we’ve helped honor each other in moments of crisis or challenge.”

During the Alliance for Progress, steeped in boisterous democratic rhetoric, US military and political interference actions multiplied throughout the continent. Military intervention is usually flanked (or vice versa) by multiple non-military activities such as USAID programs. Nonetheless, in general terms (with some exceptions), direct and open intervention started losing support from US Congress and civil society. Meanwhile, other intrusive doctrines such as counterinsurgency were born as convergence of multiple US experiences around the world, from Vietnam, Afghanistan to Cuba, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Panama and more recently, Colombia (also local experience, e.g. “long hot summer” and the repression of African American liberation movements). Since then, USAID, together with other agencies, has been very active in the country and the region, supporting or funding social activism, NGOs, universities and political parties compatible with the US exceptionalist program.

PARAMILITARY HEAVEN

Violence against leftist parties and revolutionary forces exploded across the country. Leadership and members of parties and civil society organizations created from the insurgent demobilization process were systematically massacred, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. Between 1984 and 2002, Colombian State and paramilitary organizations kidnapped, killed or disappeared around 5,000 members of the FARC-affiliated Patriotic Union: an entire political party was annihilated. Between 2002 and 2008 during president Alvaro Uribe´s time in government (himself a far-right hardliner), his military and paramilitary mates killed at least 2,300 non-belligerent civilians in extrajudicial executions by passing them as casualties in combat: the infamous “False Positives”. By 2008, Colombia turned to be the most dangerous place in the world for trade unionists. At that time, about 60% of all trade unionists in the world were assassinated or disappeared in Colombia by state or paramilitary agents. The vast majority of cases still remain unpunished.

Here another major actor in this tragedy enters: the US backed paramilitary organizations. We will address the link between them, Colombian state, political elites, landowners and drug traffickers in another article. Suffice it to say for now, that the Colombian paramilitary groups consolidated in April 1997 into the powerful Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, AUC), a far-right anticommunist armed umbrella organization. In 2006, AUC was disarticulated and 30,000 members were demobilized. Although a large number of them became reservoirs for new criminal gangs, they are still operating. By 1994, legislative decree 356 loosened the regulations surrounding security companies allowing individuals and corporations to set up multiple “special security services” known as Convivir (live together) for non-offensive operations, authorized for the use of heavy weaponry, which became a sort of façade for new and old paramilitaries.

From their primal experience in fighting Marquetalia rebels, criminal organizations grew, expanded their range of action and consolidated, penetrating everything. These groups drew support from and operated with elements of the Colombian military, police, politicians, landed elites, drug traffickers and big energy or agriculture corporations impacted by guerrilla revolutionary activities. The so-called “para-politics” scandal (breaking in 2006) triggered investigations into over 11,000 politicians and businessmen because of their relations with far-right illegal paramilitary groups or drug trafficking, sending 60 congressmen and 7 governors to jail. Land holders, cattle ranchers and agricultural and industrial corporations (e.g. Coca-Cola, coffee or banana growers) contracted their services to fight guerrillas and crack down on leftist rebel groups, agrarian leaders and trade unionists. The Chiquita banana brand, for example, admitted paying the AUC for protection and paid a total of $25 million in fines as a result. Furthermore, the company supported paramilitaries by facilitating the use of its fruit shipments as containers for weapons and drugs. Their main objective was to uphold the prevailing order that allowed them to profit.

THE COUNTERINSURGENT MILITARY DIMENSION

The Colombian Army is not just any army. According to the “The Military Balance 2019” report from the International Institute for Strategic Studies, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico are the countries that invested the most in defense and have the largest armies in Latin America to show for it. Colombia has nearly 293,000 active military units (militia 223,150; navy 56,400; air force 13,650). In 2018, the Colombian government invested $10 billion in military and defense (+ 3% of its GDP).

The Colombian Army, widely viewed today as Latin America’s best-prepared and most professional military, has become what it is as a result of the evolution of the country’s internal struggles, illegal military operations, fight against (and alongside) drug cartels and paramilitaries, repression of insurgents and the heavy influence of the US military and government.

At the turn of the century, the Colombian government lost control over half of its territory to powerful non-state actors such as paramilitaries, drug traffickers and powerful revolutionary groups. In the framework of neoliberalism decline and the emergence of new disruptive popular leaders (such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela), the US began to increase its efforts.

Pablo Escobar’s unrelenting violence against both state forces and criminal rivals led to the formation of the People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar (Los Pepes), which included drug traffickers and assassins. Many international agencies participated in the hunt for Escobar (1992-93). US Delta Force trained a Colombian police unit called the Bloque de Búsqueda (Search Block) which worked with the Pepes.

Among the military/security cooperation programs developed by the US and Colombia, it is necessary to highlight “Plan Colombia” which was initially launched in 2000. Hatched in the aftermath of the Cold War, this initiative was conceived as part of the fight against drug trafficking and coca plantations that expanded after the killing of Pablo Escobar. Quickly, the fight turned from counter-narcotics to counter-insurgency. After 20 years and $11 billion dollars invested by the US, this security aid package is celebrated by many Republicans and Democrats in Congress as one of the top foreign policy achievements of the 21st century.

This tragic saga has led to the installation of 9 military bases with US troops and mercenary contractors all around Colombia, along with the design and implementation of the so called Forward Operating Location (F.O.L.), a military scheme that allows strategic mobility, the capacity to trigger sudden wars from US bases and rapid-deploy airborne troops. This drove a proliferation of security agreements with various countries who partnered with the US in its colonization initiative.

Colombian ended up being the third-largest recipient of US military assistance at global scale, behind only Egypt and Israel. Duque will receive $448 million in aid in fiscal year 2020. About half of the money would go for military and other security programs. This budget line reached its historic ceiling with George W. Bush, who spent $600 million a year on it. During Obama’s time in office, it sat at around $450 million a year.

In August 2002, president Bush signed antiterrorism legislation authorizing Colombia to use this aid to directly combat the FARC, ELN and AUC. The same month, Álvaro Uribe became president and signed National Security Presidential Directive 18, formally expanding the uses of Plan Colombia to include counterterrorist objectives. The country was fully at war.

Along with the “legal” cooperation, as revealed by The Washington Post in 2013, the US, together with several Colombian government officials, implemented a top-secret program devastating to the insurgent groups, funded through a multibillion-dollar black budget. The US provided Colombian forces with all kinds of training and equipment, including the satellite-guided bomb kits that killed more than two dozen FARC main commanders, including the aforementioned Mono Jojoy and Reyes. American intelligence agents working with Colombian teams coordinated the strikes. Precision ammunition enabled the Colombian military to penetrate the dense jungle and obliterate rebel encampments. The CIA also trained Colombian interrogators to more effectively question thousands of FARC deserters. In 2013, the air force upgraded its fleet of Israeli-made Kfir fighter jets, fitting them with Israeli-made Griffin laser-guided bombs. It has also fitted smart bombs onto some of its Super Tucanos.

The main thrust of this offensive was to wipe out the insurgent leadership, exactly what the CIA and JSOC had been doing against al-Qaeda or ISIS leaders among others. In early March 2008, an unprecedented air strike from Colombia on a FARC camp in Ecuadorian territory was conducted which killed senior commander Raul Reyes. At the end of the same month, the mythical FARC founder Manuel Marulanda Vélez died of natural causes. In September 2010, “Operation Sodom” killed Jorge Briceño Suárez (Mono Jojoy) in another air assault. Alfonso Cano also fell in combat in November 2011. “We are breathing down his neck” then president Santos declared a few days before. Along with these figures, many more combatants were killed or detained under constant political and military pressure. Finally, the path of the Peace Accords was imposed. At the Tenth National Guerrilla Conference (2016) Peace Agreements expressed the social correlation of forces and the political-military and historical-concrete balance of the war. However, Santos himself began to dismantle the Agreements shortly after they were signed. Was the reconciliation a farce and peace nothing more than a web of lies?

From 2012, onwards a complex mechanism for dialogue was deployed, eventually becoming a milestone in international politics and diplomacy. It seemed that peace was a realistic prospect after numerous unsuccessful attempts since the 80’s: all of these ended in tragedy and thousands of deaths among those who were demobilizing and developing a public political life. Duque´s government continued Santos’ legacy: disarming, breaching and dissolving the content of the pact while trying to put forward the idea that its implementation was on the right track. Since the signing of the pact in Havana, demobilized leaders have been imprisoned and faced judicial persecution and attempts at extradition to the US; anathema, stigmatization, slander followed. More than 500 social, union and political leaders along with 200 demobilized guerrilla fighters have been assassinated since 2016. In the leadup to the 2019 elections, another 22 candidates were killed while 200 received threats. We will likely see more of this in the news in the coming days.

These are some of the main reasons why a group of FARC commanders had no choice but to resume armed struggle. In light of this situation, it seems that there was a clear objective to defeat the insurgency, which had a double effect: punishing the idea of the armed uprising against the current social order and disciplining, forestalling and containing future rebellions.

Last but not least, it is worth remembering that Colombia has been forging relations with the 29 nation NATO alliance since 2008 to finally become its first Latin American global partner. Colombia and NATO will cooperate on global security areas like cyber and maritime security, terrorism and links to organized crime.

Undoubtedly, Colombia has turned into a prominent component in the US imperialism military experience scheme.

***

SOME BASIC REFERENCES

-ANTON, Michael. 2017. America and the Liberal International Order. American Affairs Volume I, Number 1 (Spring 2017): 113–25. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/02/america-liberal-international-order/

-ANTON, Michael. 2019. Trump Doctrine. Foreign Policy magazine. Spring 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/04/20/the-trump-doctrine-big-think-america-first-nationalism/#

-BEINSTEIN, Jorge. 2018. Las nuevas dictaduras latinoamericanas.

http://www.noticiaspia.com/2018/03/20/las-nuevas-dictaduras-latinoamericanas/

-BIDEN, Joseph R. Biden, Jr. 2020. Why America Must Lead Again. Rescuing U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump. Foreign Affairs. March/April 2020

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again

-CECEÑA, Ana Esther. 2017. Los territorios de la guerra, las guerras del territorio.

https://www.alainet.org/es/articulo/188005

-CECEÑA, Ana Esther. 2010. Militarización en las Américas. Conferencia en el Foro Social Américas Paraguay.

-GONZALEZ CASANOVA, Pablo. 2017. La guerra y la paz en el siglo XXI. http://www.noticiaspia.com/2017/01/30/la-guerra-y-la-paz-en-el-siglo-xxi/

-HAASS, Richard. Liberal World Order, R.I.P. Project Syndicate. March 21, 2018. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/end-of-liberal-world-order-by-richard-n–haass-2018-03

-LINDSAY-POLAND, John. 2018. Plan Colombia : U.S. ally atrocities and community activism. Duke University Press.

-MERINO, Gabriel Esteban. 2016. “Tensiones mundiales, multipolaridad relativa y bloques de poder en una nueva fase de la crisis del orden mundial. Perspectivas para América Latina”. Geopolítica(s). Revista de estudios sobre espacio y poder, vol. 7, núm. 2, 201-225.

-PUTIN, Vladimir. 2014. Club Valdai Speech.

Leave a Reply