First part of an analysis of the Latin American “left”.

First part of an analysis of the Latin American “left”.

By Sergio Rodriguez Gelfenstein

Assessing the role of left-wing forces in Latin America after the elections in Venezuela is a real challenge that requires a conceptual review of the term “left” since, from my perspective, it is an outdated and decontextualized definition that does not reflect current reality, leading to errors that do not allow us to reach accurate conclusions.

It should be remembered that the modern term “left” comes from the French Revolution when it was associated with political options that advocated political and social change, while the term “right” was associated with those that opposed such changes. The place where the deputies who supported or did not support laws for or against the monarchy sat in the sessions of the National Assembly of France at the time of the revolution of 1789, marked for the future a conception that responded to the conditions of the debate that took place in that revolutionary era. But this has no validity in today’s world when, 230 years later, there have been profound economic, political and social transformations on the planet that have meant mutations in the future of political action and thought.

French Revolution

In this context, it must be considered that the fundamental foundation on which the revolutionary thought of that time was based upon were republican ideas and democracy as opposed to monarchy and absolutism. The emerging bourgeoisie embodied the ideas of progress, liberty, equality and fraternity, some of which are also outdated, not because they have lost validity, but because, having been stripped of their transformative content, they are empty and exclusive.

The term evolved over time, becoming associated with liberalism and later with democratic socialism and labourism, until reaching the scientific socialism of Marx and Engels. Likewise, the left began to be associated with the social struggles of workers in favor of better living and working conditions. In the 19th and 20th centuries, leftist ideas were associated with revolution and class struggle against all exploitation and alienation of workers and peoples, but also with reformism in an unfinished debate that is still present today, but not resolved.

Similarly, the paradigm of progress and progressivism consequently – so in vogue today – had its origin in Western Europe also in the 19th century. It was associated indistinctly with revolutionaries and reformists, as the former advocated a structural transformation of capitalist society, and others, only some variations that led to improvements within the framework of the system.

Europe in 1848 and later

It must be said that all this terminology has evolved over time (particularly that related to the concepts of left, revolution, reform, and progress) whose origin – as stated – dates back to the 19th century. In that period, the industrial revolution, the consolidation of capitalism as a triumphant class society and its victory over feudalism in the so-called American Civil War in the middle of that century occurred, leading to its transformation into the world’s leading power (before the end of that century). This resulted in the establishment of the bourgeoisie as the dominant class that was now located on the right of the political spectrum.

Following the revolutionary wave in Europe in 1848, which clearly defined the left-wing opposition from the perspective of defending the interests of the workers’ movement, progressivism ceased to be revolutionary and began to clearly orient itself towards reformism.

To this extent, the model of representative liberal democracy was imposed as an instrument of struggle for the bourgeoisie while it was revolutionary in its fight against monarchy and absolutism. Two hundred years later, it remains the same: a tool of bourgeois power. That has not changed, only now it is used against the people and the workers and, in general, in favor of maintaining exclusion and the use of the State for the benefit of a minority. The fight for democracy, people’s sovereignty and the permanent democratization of society requires a broader concept. Democracy is not enough to be merely representative; it must also be participatory, consultative, and must guarantee the protagonism and exercise of people’s power.

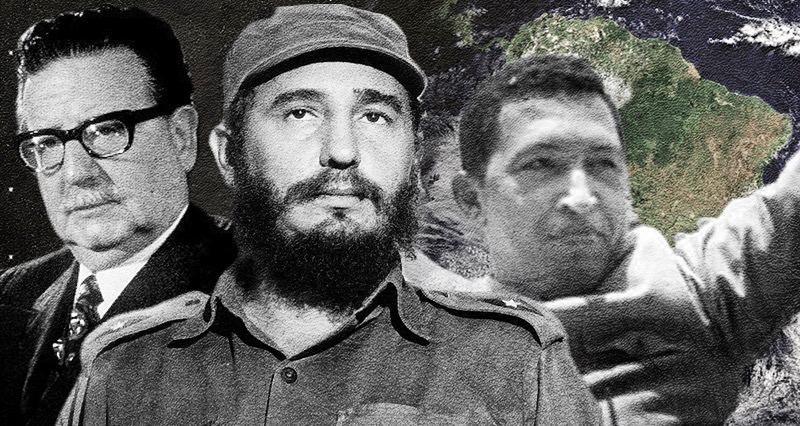

Revolutions in Latin America

This debate, placed in the world of the 21st century and specifically in Latin America, goes beyond the strictly conceptual, since it forces countries, governments, parliaments, parties and social movements to make concrete definitions regarding the future of the events that make up the current political scenario.

The analysis could be based on the most significant revolutionary events since the end of the Second World War in the region: the Cuban revolution in 1959, the victory of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1970, which began a peaceful process of transformation of society, the Sandinista revolution in 1979 and the Bolivarian revolution that began in 1999. The positioning of the left in each of these events responded to the circumstances of the moment and to the concrete historical situation of the time.

The Cuban revolution and the process of Popular Unity in Chile occurred at the height of the Cold War andof the insurgency of the decolonization and liberation movements of the Third World that would give birth to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), installing bipolarity in Latin America and the Caribbean and forcing political and social organizations to define themselves in the scenario that these events generated. The Sandinista revolution occurred in one of the situations of greatest reflux in the history of the Latin American popular movement, giving impetus to national liberation, anti-fascist and anti-imperialist struggles throughout the continent. The Bolivarian Revolution began at a time of imperialist neoliberal offensive, generating a turning point for the struggles in favor of the second independence and the advance towards Latin American and Caribbean integration.

The “lefts” – in each case – adapted to the circumstances that these revolutionary events produced in the region. Of course, they also responded to local conditions. Each of these radically transformative processes led to new adjustments, some of them quite traumatic, especially because they were unexpected for the left forces that aligned themselves around pro-Soviet, Trotskyist, Maoist, anarchist and other ideas, in vogue in the 20th century. It is worth saying, for example, that the dominant left current in the last century, which emanated from loyalty and partisan ties to the Soviet Union, did not support and was even against the Cuban and Sandinista revolutions that occurred when the world was still organized from a bipolar perspective. The triumphant processes in Cuba and Nicaragua did not respond to that logic; they were national liberation movements rooted in their own nationalist and revolutionary ideas (Martí and Sandino) that were quite unknown and far removed from the discussion of the traditional left in the region.

Traditional Left approaches national democratic revolution with scepticism – first

All the left, socialist and revolutionary forces, including the communists, not without resistance, rushed to join the new revolutionary wave of the left that these historic events signified. Almost unanimously, with some reservations, especially from some Trotskyist sectors, they gave their support to the novelty that emanated from popular victories in the “backyard” of the empire… and that had been achieved without the sponsorship of the Soviet Union and even with its opposition. Both processes at the time meant strong impulses to the struggle and unity of the left.

The Bolivarian revolution took place in a different context and under different circumstances, three of which were very important: first, the bipolar world no longer existed, and the United States was running riot on the planet. Second, it did not emerge from a revolutionary war of national liberation or from an armed popular insurrection but came to power through elections (just as the Unidad Popular had done with Salvador Allende in Chile in the 1970s), defeating the entire network of imperial control that had been entrenched in Venezuela for forty years. Finally, unlike the previous ones, the Bolivarian process was not led by political organizations or leaders elevated from the revolutionary armed struggle, but by a nascent organization with a leader from the armed forces of the ruling regime who emerged from it to lead the people to victory.

Such a scenario, once again, led to the rearrangement of leftist forces. Few were those who from the beginning trusted in the revolutionary impulse that Commander Hugo Chavez gave to the country’s patriotic forces. Attached to a certain theoretical conservatism, the majority did not look favorably on the idea that a military man derived from the armed forces could unleash and lead a process of revolutionary and cultural transformation of society.

Under these conditions, the Bolivarian process began to develop. It would be lengthy to mention all the milestones that it had to go through, and it is not the objective of this work to do so. I can only say that the initial astonishment gave way to sympathy, and from there to support, which seemed to be verified by the fact that in April 2002, the United States organized, financed and structured a coup d’état to overthrow Commander Chávez.

The event, which caused conflicting opinions in what until then was called the Latin American left, gave way to stupor when for the first time in the history of the region an alliance of the people with the military put an end to the attempt and in less than 72 hours and reinstated Commander Chavez in power. From then on, the various “lefts” not only supported, but sought shelter and even financing in this powerful country that, unlike Cuba, Nicaragua, supported by the heroism and resistance of its people, had the largest oil reserve in the world, which Commander Chavez wanted to put at the service of the liberation of the people.

“Leftist geniusses” and the Bolivarian Revolution

“Leftist geniuses” (especially intellectuals) appeared from all over the region and the world, who knew everything but had done little or nothing in their countries, requesting “contributions” for the most unlikely projects in exchange for “saving Venezuela.” They offered their “brilliant and “indispensable services” to do what we Venezuelans supposedly do not know how to do, which seemed to be almost everything. They contrast with the impeccable internationalist vocation of Cuba and of some revolutionary fighters who have come modestly, silently and in solidarity to seriously support Venezuela.

They did not realize that the Venezuelan people made a revolution and have sustained it under the empire’s nose, while they have limited themselves to writing a few books and articles, becoming insignificant figures in their own countries. This “fauna” made up of what could be called “left-wing mercenaries” formed and still form part of the opportunism that is also a link in this broad spectrum that makes up the so-called “left” of the 21st century. Since 2000, they have jumped from process to process in Latin America, in some cases with great success, especially for their own pockets.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Leave a Reply