A Man of Many Names

When he referred to the collapse of the Soviet Union as, “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” – Western pundits labelled him a communist. Mainstream periodicals, like Politico and Newsweek, and anti-Russian propagandists call him a fascist – on account of a “hyper-masculine personality cult” and “high-levels of repression,” among other authoritarian-sounding concepts.

To some, Vladimir Putin is the new Josef Stalin – to others, he is the new Adolf Hitler. Many liberal so-called “experts,” in their attempts to put a name to this illusive concept they are hard pressed to explain, simply call his leadership style the ideology of Putinism. Realistically, Vladimir Putin is neither an aspiring General Secretary of the Communist Party nor the Fuhrer of a new Russian Empire. The role he plays in the grand performance of history is not actually so unique as to necessitate the creation of a new ideological category either.

In fact, Putin’s rise to power and the particular social forces from which his administration draws its political authority cannot be properly understood using liberal thinkers’ limited capacity for understanding 21st century political expressions and their parallels of the past. Karl Marx’s dialectical materialist approach to history, however, does offer an explanation – the concept of Bonapartism.

Louis Bonaparte: The Prince President

Marx’s groundbreaking 19th century work, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, explores the political career of both the first president and last monarch of France – Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew Louis Bonaparte. For the student of political economy using a dialectical materialist mode of analysis, the history of Bonaparte’s reign does not only offer insight into the political turmoil of the mid-19th century. It provides an archetype for the political category of the Bonapartist leader – an independent executive power ruling over a society of equally-matched social classes. After all, it was amidst political struggles between the radical traditions of the French Revolution of 1789 and the monarchical restorations which followed its overthrow, that Louis Bonaparte was elected President of the Second French Republic in 1848.

He inherited a country being drawn-and-quartered by parliamentary political struggles between the monarchist Party of Order representing an alliance of big business and landed interests, bourgeois republicans, the socialist montagne, and Bonapartists who sought to restore the French Empire. By the end of his constitutionally-mandated term limit in 1852, constant infighting between these factions had rendered nearly all of them politically inept, with the exception of Bonaparte’s greatest parliamentary ally, the Party of Order, and left the French people in dire want of political stability.

From a class perspective, it had seemed France’s capitalists were triumphant over the country’s workers and small enterprise owners – represented by the then-defeated montagne and republicans, respectively. But the Party of Order failed to function as a political body. Its internal contradiction between the interests of industry and agriculture rendered it incapable of understanding, “neither how to rule nor how to serve…neither how to cooperate with the President nor how to break with him,” according to Marx’s recollection of events.

Bonaparte and his bureaucracy “numbering more than half a million individuals” stood alone as the only political force capable of ruling and restoring order to the country. They had the backing of military officials and armed groups associated with the pro-Bonapartist organization Society of December 10, as well as popular support from masses of France’s peasantry which had long felt betrayed by the rest of political society. With the French capitalist class’ only option “to save its purse” being to “forfeit the crown and the sword that is to safeguard it,” Bonaparte threw out the constitution and declared himself Emperor in 1852, establishing the Second French Empire that would keep “all classes equally powerless and…on their knees.”

A political order which came to be characterized by an 18-year-long stalemate within the French class struggle was born and Bonaparte’s policies tried to affect the nation as a whole to maintain that balance. Under his reign, reconstruction plans for major cities including Paris, Marseille, Lyon, and others were implemented in an effort to improve the infrastructural condition of the nation. Railroad expansion and agricultural modernization programs greatly improved the French economy, reduced poverty, and turned the country into an agricultural exporter. In terms of social reforms, Bonapartist policy came to be associated with the restoration of universal suffrage, the right for workers to organize trade unions, and even the ability for those workers to strike.

Although far from an example of governance in the name of working class interests, Bonaparte’s administration accomplished much in the way of improving the nation’s vitality, acting as a half-way house between France’s proletarian revolutionary experiments, the emerging industrial bourgeoisie, and its centuries-long feudal order.

Vladimir Putin: 21st Century Louis Bonaparte

About four and a half years after Vladimir Putin was elected President in May 2000, General Secretary of the Communist Party of Russia Gennady Zyuganov declared that “a Bonapartist regime had been established in Russia.” The country’s new Head of State, indeed, shared many similar traits with the 19th century monarch in terms of the conditions in which he came to power, who he relied on to retain power, and what effect his administration had on the country.

At the eve of Putin’s presidency, Russia found itself in a very similar historical condition to that of mid 19th century France. Nearly seven decades of life in the socialist USSR – the world’s first federated workers’ state – had come to an end not long before then. The capitalist restoration that followed, under the deeply unpopular Boris Yeltsin administration, saw the emergence of oligarchs who callously trampled over the working man and gangsters who killed with impunity, caring little for the rule of law. The new regime attempted to shock society backwards – failing to realize that the country had been irreversibly propelled forward, as the newly reorganized Communist Party of Russia was anything but defeated.

On the backdrop of this social dissonance, Vladimir Putin, equipped with the KGB, or “silovik” according to Western political scientists, connections made throughout his career as an intelligence officer and the support of a state bureaucracy left over from the USSR, inherited Russia by popular vote. As did Louis Bonaparte’s coup d’etat of 1852 bend the Party of Order to the will of himself and the state bureaucracy, so too did a “grand bargain” struck between Putin and the oligarchs, who made a fortune pillaging the country’s economy, see the latter sacrifice their crowns to save their purses. The capitalist class was put on a leash, overt gangsterism was crushed, and order was restored.

This arrangement paved the way for the successful implementation of national priority projects aimed at developing public health, education, housing, and agriculture. Resulting in large part from these projects, Russia has become the world’s leading wheat exporter, poverty has been cut in half since the beginning of Putin’s presidency, and wages have seen significant increases nation-wide. It is also important to mention the widespread expansion of Russian oil-pipelines under Putin, which have had a positive economic impact comparable to that of Louis Bonaparte’s railroad expansion plans.

The Anti-Imperialist Bonaparte

However, there is a key difference between Louis Bonaparte and his 21st century Russian counterpart. The former’s ascension to the throne saw the short-lived restoration of an Empire, the unsuccessful military adventures of which resulted in the deposition of its own monarch. In the case of contemporary Russia, Vladimir Putin is anything but an emperor.

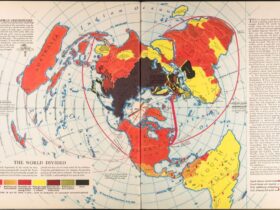

On virtually all sides, Russia is threatened by NATO military bases, missile batteries, and routine joint-invasion simulations with powers hostile to Moscow. Washington has made regime-change its policy on Russia’s doorstep, with Ukraine and Belarus being the latest flashpoints of foreign sponsored insurrection. Inside the country, opposition activist Alexei Navalny, who studied at a Yale University fellowship program renowned for its production of color-revolutionaries, continues to accuse the Russian state of breaching international law, with the help of the Western media.

Clearly, Russia has been on its backfoot since the collapse of the USSR, as it has attempted to deflect the West’s many imperialist attempts to infringe upon its sovereignty. And yet Washington’s narrative accuses Moscow of election meddling, as well as attempting to destabilize the fabric of American society – a clear-cut case of political projection. The Russian government’s relative inaction with relation to the recent storming of the Capitol reveals to any onlooker the absurdity of the prevailing Western worldview towards the East.

It is true, Russia is no longer the flagship republic of a socialist federation that once inspired the world with its ideals of revolutionary liberation. But Vladimir Putin’s Bonapartist rule has thus far protected Russia from the dictatorial grip of global finance capital. For as long as such an administration holds power, Western anti-imperialists should struggle tooth-and-nail to protect it from harassment by the imperial core in which they live.

Leave a Reply