ASEAN countries hope to pragmatically benefit from the rivalry between the two global powers

ASEAN countries hope to pragmatically benefit from the rivalry between the two global powers

By Orçun Göktürk, Beijing / China

President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, paid visits to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Cambodia during a period when the trade war with the United States was intensifying. These countries hold great significance for China. Since the first trade war that began in 2017, these three countries have become major hubs for investments by large Chinese companies. China is now the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in these nations. The main reason is the Chinese companies rushed to set up production facilities in the region to avoid U.S. trade restrictions.

China is the largest foreign direct investor in Cambodia (more than 40% of total FDI in the country in 2023 came from China). In Vietnam, Chinese giants have made heavy investments in manufacturing, infrastructure, and energy projects, and since 2017, China has also become Vietnam’s largest foreign investor. In Malaysia, Chinese investments stand out particularly in energy, green technology, electronics, and logistics. Malaysia is also a key hub for China’s “Digital Silk Road” initiative. In short, all three countries are China’s top trading partners and, as members of ASEAN (with Malaysia holding the rotating chairmanship this year), they play an indispensable role in China’s economic relations with both the region and the world.

From SEAT to ASEAN: A Project to ‘Protect Asia from Communism’

Before returning to Xi’s visits, let’s briefly examine the background of ASEAN. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was founded in 1967 during the Cold War, largely as an extension of the United States’ anti-communist strategy against China and the Soviet Union. At its core lay SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization). Founded in 1954 under the leadership of the U.S. and the U.K., SEATO included the U.S., U.K., New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, and Australia, was a direct military alliance aimed at halting communist expansion. However, as it proved ineffective, ASEAN emerged 13 years later.

At that time, the Vietnam War was raging across the region, and communist movements were active and strong in countries like Laos, Cambodia, and Indonesia. This was a nightmare scenario for American geopolitics interest. To prevent a potential domino effect, regional countries were gathered under an anti-communist umbrella.

ASEAN also underwent transformations due to global political and geopolitical changes. After the Cold War, ideological concerns moved to the background. Between 1995 and 1999, former “enemies” such as Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia joined ASEAN. With this expansion, ASEAN became a full-fledged regional organization. In 1997, the ASEAN+3 platform (including China, South Korea, and Japan) was established.

China’s miraculous economic development presented great opportunities for ASEAN. The China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement was signed in 2002. As of 2020, China became ASEAN’s largest trading partner, and by 2024, bilateral trade reached a massive volume of $963 billion.

ASEAN describes itself as a bloc that is “free from great power rivalry,” “non-aligned,” and “neutral.” Phrases such as “neutral but open to cooperation with all” are regularly emphasized in annual summit communiqués.

ASEAN’s Role in the U.S.-China Competition

Let’s now return to Xi’s visits to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Cambodia. On April 8, U.S. President Trump — after first announcing and then delaying for 90 days — introduced new tariffs targeting nearly the entire world, with ASEAN countries being second only to China in terms of the number of tariff threats.

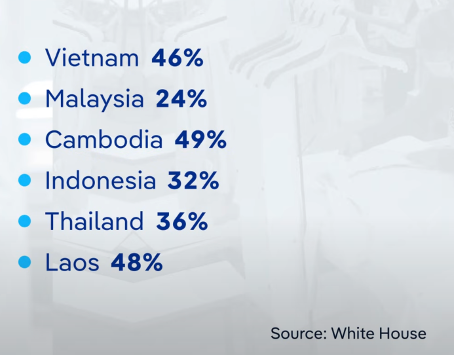

Figure 1: Trump’s Tariff Threats to Southeast Asian Countries

The table in Figure 1 illustrates a Trump strategy designed to force ASEAN countries into choosing between the U.S. and China. However, this strategy contradicts ASEAN’s declared principles of “strategic autonomy” and “balance diplomacy.” The open trade and regional integration spirit that lies at the heart of ASEAN will be tested against Trump’s pressure.

Xi Jinping’s trip was organized based on that very “ASEAN spirit.” ASEAN countries make up China’s largest trading bloc. The purpose of the visit was to reassure neighboring countries against Trump’s economic bullying. Xi’s consecutive visits reflect a strategy to keep the region aligned with China in the face of rising tensions triggered by Trump’s tariff threats. It’s worth noting that, during Xi’s tour, the media in these countries were filled with headlines emphasizing themes like “friends with all, enemies with none.”

During Xi’s visits, the continuation of high-speed rail and infrastructure investments, digital economy and AI cooperation, and green energy and development projects in the region was emphasized. The Chinese leadership sent a clear message to the region: “China is not decoupling, and it’s not abandoning you. If the U.S. offers sanctions, we offer cooperation and investment.”

Certainly, Trump’s tariffs put ASEAN countries in a difficult position. However, ASEAN’s institutional memory and the ASEAN spirit make it likely to reject the binary “either with us or against us” logic offered by Trump. Instead, ASEAN countries hope to pragmatically benefit from the rivalry between the two global powers.

‘The Asian Era of Globalization’

Finally, it’s worth noting Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s remarks regarding Xi Jinping’s visit. The Chinese diplomat interpreted Beijing’s deepening regional diplomacy as a sign that “globalization has entered the Asian era.”

Wang Yi emphasized that President Xi’s trip to the region marked his first overseas visit of the year. In the official briefing published on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, Wang stated: “China is approaching its surrounding regions with a broad and strategic perspective, demonstrating a truly long-term vision. Globalization has entered its ‘Asian moment,’ the world’s center of gravity is shifting to Asia, and China is a major engine in this transition.”

Wang’s comments are highly significant. While the U.S.—formerly the leader of globalization—has turned towards protectionism, China has emerged as the new leader and spokesperson of globalization. In a sense, the world has turned upside down.

Leave a Reply