On 16 June, armed clashes took place on the border between China and India. The Indian side later reported that 20 soldiers were killed. There is no information about deaths on the side of the Chinese military. This bloody collision is the first in nearly 40 years. The Chinese claim they were attacked first. The media reports that the incident was a hand-to-hand fight, where stones and sticks were also used.

Geopolitics of conflict

The bloody incident took place in the Galwan Valley in the disputed Aksai Chin-Ladakh area. The region is located at the junction of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (PRC), Pakistan and India. The dispute over the area caused the 1962 India-China war.

The roots of the conflict, as well as many in the South Asian region, date back to colonial times. There is almost no permanent population in the disputed region, but the land area is of strategic importance. It was joined to British India (British Raj) in 1914 by a secret treaty between the colonial authorities and Tibet (whose sovereignty was not recognized by Chinese authorities at the time). China does not recognize this agreement.

One of the reasons for the Indo-Chinese War of 1962 was the fact that India discovered a road built by China through the disputed territories. China National Highway 219, which connects Tibet and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, passes through, and has therefore acquired strategic importance for China. Most of the road is located above 4000 m above sea level.

As a result of the 1962 war, the Line of Actual Control (LAC) was drawn to divide Chinese and Indian troops in the region. However, there are occasional skirmishes despite the agreements between India and China reached in the 1990s, as the line is not a real border and both countries consider the territories their own.

In 2017, there was a serious clash between China and India brought about by China’s road in the disputed territory of Doklam – another part of the border between India and China. After that, however, tensions reduced for many years. In 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Wuhan agreed to defuse the situation.

In May 2020, however, new clashes erupted at several points on the India-China border in Aksai Chin, leading to new tensions between the countries. Then the Chinese military strengthened its presence in the region.

Indo-Chinese confrontation

Tensions on the border between India and China are a consequence of the growing geopolitical confrontation between the two countries.

COVID-19 was used by the US and its allies to boost their attack on China. India, which Washington sees as a counterbalance to China, is being set-up to replace China as a production center for the West. At the same time, India itself has limited opportunities for Chinese investments.

Will India maintain its sovereignty, or be used by the US in its confrontation with China?

India is also actively developing military and political ties with the United States.

Flirtations with the US have an obvious strategic goal – the flow of investment, which should enhance India’s economic growth. However, the US has proven that it is not a convenient trading partner. Despite Trump’s pompous and ostentatious visit to India in February 2020, the American president showed that he was not ready to make significant concessions to India. A new trade deal was never concluded to replace the previous agreements undermined by the on-going tariff war. Recall that just a year ago, Trump deprived India of the status of a beneficiary developing country, thereby worsening the position of Indian companies in the US market.

However, China and India have actively increased their trade cooperation in recent years. China is one of the largest investors in India, especially in high-tech companies – China has invested more than $4 billion in this sector alone.

Roads and maps

The territorial dispute itself should be seen as a second level factor. However, unresolved problems at a time when relations are generally deteriorating can lead to conflict. Given that both India and China possess nuclear weapons, and that Aksai Chin is in the Kashmir region where India is in tension with another nuclear power, Pakistan, an escalation of the conflict is likely to develop into a series of regional conflicts.

As mentioned, many of the conflicts between India and China have been over the construction of roads in the disputed region, and the same is happening today.

The Darbuk-Shyok-DBO Road in eastern Ladakh is being built in close proximity to the LAC. Many experts believe that Indian road works may have resulted in increased opposition from China.

In May, a unilateral road link between Dharchula in the Indian state of Uttarakhand and Lipulekh, claimed by Nepal, was opened. The road passes through the disputed Kalapani territory. India’s Defence Minister Rajnat Singh attended the ceremony on May 8. On May 20, Nepal issued its new political and administrative maps, listing Lipulekh, Kalapani and Limpiadurias as Nepalese territory. The Nepal Army later stated that it was ready to confront the Indian Army. At present, Nepal has a pro-China Government in power.

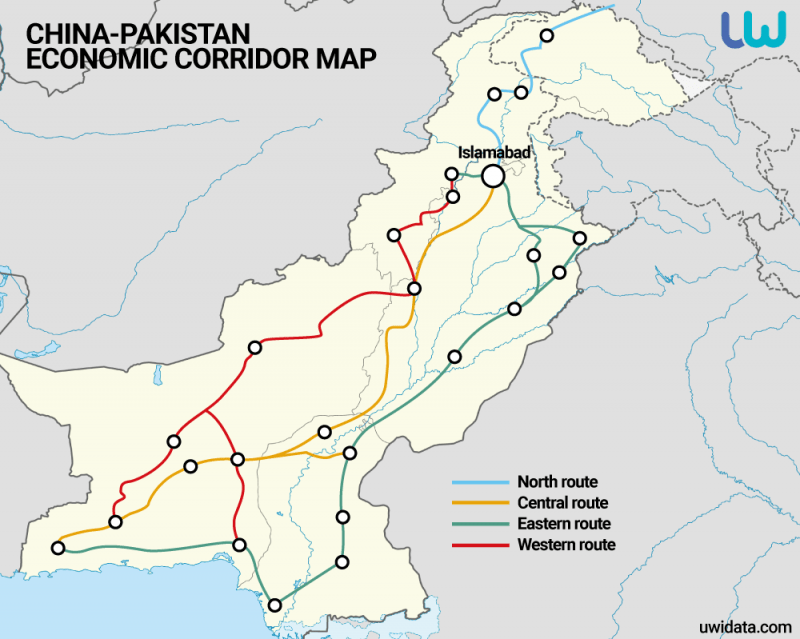

Finally, the main conflict in the region – the issue of the status of Jammu and Kashmir – is directly linked to the problem of transport arteries. Part of the region, which India considers its own, is now administered by Pakistan, and it is through these areas that the most important part of the Belt and Road initiative – the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – passes, uniting China with ports on the Arabian Sea.

In 2019, Article 370, which gave Jammu and Kashmir special status, was removed from the Indian Constitution; the former state is now divided into two allied territories, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. India’s military presence in the region has been strengthened. Both Pakistan and India saw this as a threat to their interests.

A holistic approach

The problem of increasing tension on the Indo-Chinese border is multilayered. The first and most important layer is the tension between countries, the struggle for spheres of influence in South Asia and the Himalayan region in particular. In the dispute with China, India finds a partner in Washington.

Interestingly, India is interacting with the US as if it were just one of the great powers. In other words, for New Delhi, Washington is a partner in an already established multipolar world.

The US, although it has been talking about the competition of great powers since the publication of the new National Security Strategy 2017, has not really given up fighting for hegemon status (which implies a unipolar world system).

The tragic events connected to the LAC may propel India towards a more pro-American strategy. However, by uniting with the US, India is strengthening the unipolar Washington-dominated world, despite that New Delhi has traditionally supported multipolarism. India is allowing itself to be used in the American-Chinese confrontation to Washington’s benefit.

How the situation develops depends on the strategy the Indian leadership chooses: either it will find a place in the American agenda despite being fraught with security problems in Kashmir and stand in opposition to BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, or it will take an independent course directed toward multipolarism.

For India to choose multipolarity, the Chinese side must also have the ability to compromise. Given the death of 20 Indian military personnel, which led to a surge of anti-Chinese sentiment in Indian society, China will need to take action to fix relations.

Much will depend on how much other nations are willing to promote reconciliation between India and China. On June 22 on Russia’s initiative, virtual trilateral negotiations at the level of foreign ministers of RIC (Russia – India – China) are to be held. Border issues will be discussed, among other important issues.

Regional cooperation

The second layer in the Himalayan conflict is the border itself, or rather, the fact that the LAC is not a border in the full sense of the word. A final delineation should be the ultimate goal of the dialogue between the two Powers. The current upsurge in border violence shows that the existing institutions and formats for cooperation between the two countries’ military at the border are insufficient.

There are no effective protocols for interaction that would avoid tragic incidents. There is enough work for both civilian and military diplomats in this area. Despite the existence of a Confidence Building Measures (CBM) regime based on at least mutual information between the parties, it can be concluded that this regime does not in fact contribute to confidence-building. However, this does not mean that it must be eliminated, as some have called for. Quite the opposite.

There is also a need for confidence-building measures between Indian and Chinese troops in general: common exercises, shows, war games, development of military-to-military ties. The SCO format gives the certain possibilities for this way.

More than ever, there is a need for detailed dialogue among Indian, Chinese, Nepalese and Pakistani experts, for the rejection of propagandistic clichés.

The Indo-Chinese clashes, as well as the Indo-Pakistani clashes last year, will be a challenge for the SCO as long as all three countries are members of the organization. It is in the interest of the countries of the Organization to develop de-escalation mechanisms.

Perhaps it makes sense to discuss the peacekeeping component of the SCO and its implementation in the areas of greatest tension between India and China, the establishment of SCO observation posts with military personnel from the third country (Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan) or the involvement of experienced military countries interested in SCO (Turkey).

Protocols for the establishment of road networks in disputed regions should also be formalized. But that means the common will to reconcile infrastructural strategies of the main actors in Kashmir. If this is possible, it gives impetus for the development of the region.

Make Kashmir Great Again

Given that the Kashmir issue has long been a stumbling block between India and China, not just India and Pakistan, there is a great need for an ongoing international dialogue on the issues of the Greater Kashmir Region, which can include two Indian allied territories: Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, as well as Pakistan’s Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan and Aksai Chin territory.

Historically, Kashmir was a crossroads of caravan routes (including the historical Silk Road) between the Far East, Central Asia, Middle East and South Asia. The north of Kashmir was populated predominantly by Muslims, the South by Hindus, and the East by Buddhists. However, in general, these faiths are believed to have managed to maintain the necessary balance in relations and to have developed a common identity.

Kashmir has been a point of contact between Hindu civilization, Chinese civilization and the world of Islam for many centuries. Now, it’s turned into a conflict zone. A once flourishing region, a former center of regional trade and international contacts crosses many dividing lines, though it could become an important transit corridor both in the broad east-west direction for the Belt and Road initiative as well as in the north-south direction (from India to Central Asia).

It seems productive, at least in intellectual discussions, to single out Greater Kashmir as a separate geopolitical reality, potentially working towards its formalization in the form of a Transborder Region (like a Euroregion in the EU).

This would require rejecting any kind of revanchism by “experts”, regional media, and politicians. To move forward and realize Kashmir’s tremendous potential, everyone will have to be in agreement. India, Pakistan, and China will not be required to redraw their maps, but they need to learn how to deal with the actual situation and recognize that the territorial control zones will not change.

This will require a refusal to pander to separatists and extremists of all kinds. Any accusations of India’s negative treatment of Muslims in Kashmir will immediately boomerang into criticism of China in Xinjiang. Terrorism, extremism, and separatism are a threat to both India, China, and Pakistan. Supporting them in any form will spark an equivalent reaction across the border, and essentially lead these countries to digging a common grave. In the area of strategic transport projects, it would be desirable to exchange mutual guarantees – Indian security guarantees from CPEC, China and Pakistan – for a possible direct Indian exit through Greater Kashmir to Central Asia and further through Russia to Europe.

However, movement towards reconciliation is only possible if all parties to the conflict are ready to struggle for it.

Leave a Reply