The 33rd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Heads of State and Government of the African Union took place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The main topic of the event was “Silencing the Guns: Creating Conducive Conditions for Africa’s Development.”

Despite that security is the main theme of the summit, precious little has been done to stabilize the situation on the African continent, as evidenced by the increased attacks by terrorist organizations and local fighters. The new crises in Cameroon and Mozambique are taking place alongside protracted conflicts in Libya and South Sudan, African Union Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat reminds us.

The continent is suffering because of “terrorism, intercommunal conflict and pre- and post-election crises,” he added.

France, as a former (and in many ways contemporary) colonial country, is desperate to find any opportunity to retain influence in the region, including through military means. The day before the summit, Paris decided to send an additional 600 people to Africa as part of Operation Barkhane, while Macron continues to actively tour the continent.

However, anti-French sentiment is only growing. Why hasn’t Macron been unable to achieve his goals?

Terrorist attacks and ‘Unprecedented terrorist violence’

The region is experiencing an “unprecedented” rise in violence related to terrorism, according to the United Nations.

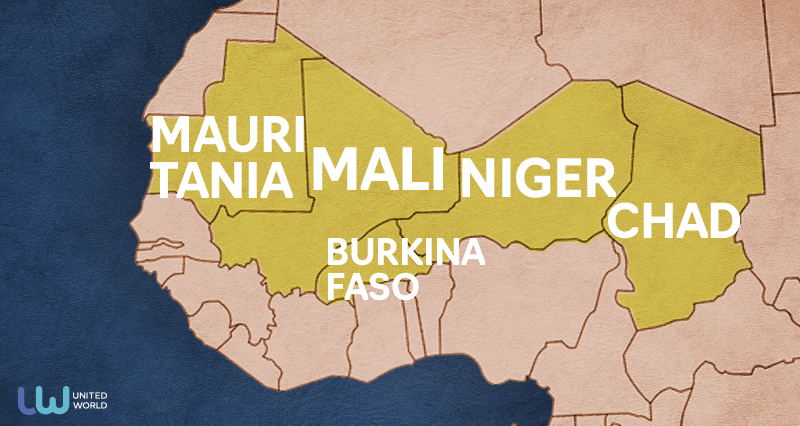

Mohamed Ibn Chambas, UN Special Representative and Head of the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), highlighted the rise in terrorist violence across the region of West Africa and Sahel, saying: “the region has experienced a devastating surge in terrorist attacks against civilian and military targets.” According to Chambas, the geographic focus of terrorist attacks has shifted eastwards from Mali to Burkina Faso and is “increasingly threatening West African coastal states.”

Chambas paid particular attention to the victims of terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, which have increased fivefold in three years. More than 4,000 deaths were reported in 2019 alone, compared to approximately 770 in 2016.

Among the most active terrorist groups in Africa, the following can be highlighted:

Al-Qaeda

Al-Shabab

ISIS (with departments in different countries)

Boko Haram

Egyptian Islamic Jihad

These are just a few of the groups active in the region, some branches of larger terrorist organisations.

The problem of terrorism is espeically sharp in Sahel countries (G5) – Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. The Islamic State has a presence in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Ansaroul Islam (Burkina Faso, Mali) and the Macina Liberation Front (Mali), both affiliates of Ansar Dine.

There is also a significant problem with tribal violence. Sometimes these tribes act alone, sometimes they collaborate with terrorist groups to achieve a common goal or strike a blow against the French troops increasingly encroaching on the area. The Tuaregs remain one of the most active groups in the Sahel, and it is important to take into account individual conflicts that further destabilize the region, such as those in Mali where there are particularly fierce battles between Dogon farmers and Fulani pastoralists at the height of the dry season.

In the last month alone in the Sahel, there was an attack in Mali which killed 20 local soldiers in Sokolo (near the Mauritanian border), another which left 32 civilians dead in Burkina Faso after militants attacked and burned a local market with people, and a jihadist attack in Nigeria that killed 174 people.

Radical groups tend to thrive in areas where there is either a weak or non-existent government, where the power vacuum plays directly into the hands of terrorists. These groups use Islamist ideology to build bridges between different ethnic groups, convincing them to fight for Islam rather focus on petty tribal conflicts.

In some cases, jihadist groups provide protection and social services to these marginalized communities.

We have written before about the rise of terrorism in the Sahel region:

Sahel chaos: How terrorists are taking power in Mali, Niger and the region as a whole

French military presence

During the Cold War, France was called the “gendarme of Africa”: between 1945 and 2005, France carried out about 130 military interventions on the continent. To this day, France, relying on its military bases in the region, Paris considers itself entitled to deploy troops and intervene in its former colonies to defend its interests. France openly intervenes in domestic political processes and uses its resources to fuel the revolutionary mood across the continent. Certain countries in Africa are more like massive resource deposits managed from Paris.

France has permanent military bases in Djibouti, Gabon, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, and retains the “right” to intervene in ‘Francafrique’ under the pretext of fighting terrorism.

Officially, the French forces in Operation Barkhane have 4,500 personnel – now, with the edition of 600 more soldiers, it’s up to 5,100. It has been reported that military personnel remain there under the cover of peacekeeping forces. Officially, there are over 13,000 people from the UN in Africa.

There are about 7,000 soldiers from Americans in the region, and about 2,000 more are conducting exercises in African countries.

Françafrique pic.twitter.com/2fGAUZF85s

— Carlos Ruiz Miguel (@DesdelAtlantico) December 8, 2019

Africans are united in their dissatisfaction with France

Increasingly, one hears from Africans that the more French troops present in the country, the further things escalate. To a large extent, this is due to the fact that rebels and rebel groups tired of Paris’ influence are increasingly targeting security forces, carrying out suicide attacks and undermining foreign representatives. Militants also often target UN peacekeepers, such as we saw in the recent slaying of numerous delegates in Mali.

Tribal leaders, despite their personal conflicts, stand in solidarity against foreign invaders. According to Dogon leader Mamadou Togo, Paris profits from the instability in Mali and plans to “recolonise” the country. According to Fulani leader Mahmoud Dicko, the UN mission and the international community are failing Mali, and wasting their money on “their own comfort.”

It is possible that some forces are deliberately trying to destabilise the situation in the Sahel, Dicko believes. In his assessment, external forces are provoking conflicts between different ethnic groups to foster destabilisation.

“I say to leave us alone, to leave the Sahelians between us,” he told Global News.

“We are brothers, we have lived together for millennia. We have a mechanism to settle things between us. If we are left alone, we ourselves will find a solution to this problem.”

https://twitter.com/PaolaAudrey/status/1208506535174909952

Economic and monetary occupation

French companies such as Total oil thrive on cheap African resources.

According to official data, there are over 1,100 French companies present in Africa and over 2,109 subsidiaries.

The French currency, the CFA franc, remains an important factor in post-colonial control in Africa. Now there are plans to replace it with the African currency, the Eco, as Macron noted during a meeting with the president of Côte d’Ivoire Alassane Ouattara. The plan looks perfect on first glance: Paris is finally leaving with 50% of currency reserves in the Treasury of France, and the initiative is being passed into the hands of Africans.

"L'Eco verra le jour en 2020, je m'en félicite", a déclaré le président français au cours d'une conférence de presse avec son homologue ivoirien. Le franc CFA était "perçu comme l'un des vestiges de la Françafrique", a-t-il estimé #AFP pic.twitter.com/JVIzxHOaWO

— Agence France-Presse (@afpfr) December 21, 2019

However, things are not that simple. First, there are ideological issues: Africans are outraged that the project is being overseen by France. Secondly, the Bank of France will continue to guarantee currency parity against the euro, and thirdly, the new currency will be directly linked to the European Central Bank.

In other words, Macron will simply link Africa’s currency dependence to European structures rather than directly to France. These structures are, as we know, under the control of major bankers who are not at all interested in the sovereignty of the African continent.

The West African CFA is used in eight countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo), while the Central African CFA is used in six other countries (Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon).

Europe’s involvement is based purely on economic interests and desire to control these 14 countries: according to the International Monetary Fund, these countries are home to 155 million people, 14% of Africa’s population, which is about 12% of the continent’s GDP.

Furthermore, the CFA franc being renamed the “ECO” is puzzling. The ECO is the name chosen in June 2019 in Abuja by the fifteen countries of ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) to designate the single West African regional currency in the making, France inter writes.

“Who gave them the right to rename the CFA franc ECO when they have not yet all met the criteria for entry into the ECO monetary zone defined within ECOWAS? How can we understand this hasty declaration by Macron and Ouattara which maintains France as the alleged “guarantor” of the CFA franc renamed ECO, as well as the fixed parity with the euro, while ECOWAS requires for the launch of its single currency the total withdrawal of France from the monetary management of WAEMU countries?”

It is curious that France has always and with all its might opposed the elimination of the French currency system in Africa. When the first African leaders tried to get rid of CFA (Sylvanus Olympio in Togo, or Modibo Keïta in Mali Republic, David Dacko in Central Africa and many others), as if by “coincidence” they were always killed or overthrown by the French military in a coup.

According to the famous anti-globalist activist Kemi Seba, the Eco initiative is essentially a neocolonialist plan to keep control of Africa. He accused both France and the Ivory Coast of “acting unilaterally” and overriding regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States in its decision.

???? EN DIRECT DE "PAU "

pour une mobilisation Anti #ECO.

Nous dénonçons la complicité de @EmmanuelMacron à vouloir maintenir le néocolonialisme , et le nazisme monétaire en Afrique.

A bas l’impérialisme français nous réclamons la fin de la #FrançAfrique #LDNA pic.twitter.com/JQjTJouUWd— Ligue de défense Noire Africaine (@LDNAOFFICIEL) January 13, 2020

Has Macron been defeated?

There have been 67 coups in 26 African countries over the past 50 years, and 16 of these countries are former French colonies. 61% of the coups took place in French-speaking Africa, which means that 45 of the 67 coups took place in former French colonies.

French presence only irritates the local population and gives rise to pan-African sentiment. Since many African rulers are essentially American or European puppets and do not have the political will to get rid of transnational corporations, the crisis stricken local population prefers to deal with bandits, even at the risk of terrorist attacks. Despite economic growth over the past two decades, very few Africans have benefited. Inequality has reached extreme levels in the region, according to a recent Oxfam report. In addition to objectively poor performance, people are annoyed that a few multibillionaires and multinationals are siphoning their natural resources and relying on them as a cheap of their labour force, creating truly horrific living conditions.

France is perceived as an invader across the continent, which is why it is not surprising that we are seeing more and more protests focused on decolonization and freedom from the influence of Paris. The concept of ‘Francafrique’ itself now has extremely negative connotations.

Given its long colonialist history and current aggressive actions, it is clear that France is using terrorism as an excuse to intervene in African countries. According to local sources, Paris supplies weapons to terrorists while claiming that it is fighting terrorism, which helps it to justify sending more and more soldiers to the Sahel. Recently, Nigerian customs officers confiscated weapons (sent to local terrorists by Boko Haram) hidden in a container on behalf of a French organization. France is unwilling to invest in the development of the country – it benefits too much from chaos which allows it to maintain control of the region and siphon out resources on its own terms.

However, it is clear that Macron is growing tired of things not going according to plan. He is gradually losing international support for his African adventures, while France remains bogged down in a complex military game.

“If the Americans were to decide to leave Africa it would be really bad news for us,” Macron said after US President Donald Trump announced the reduction of military presence on the continent.

The United States provides intelligence, logistics and unmanned drone support to French and regional forces. The US Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Mille, on his way to a NATO conference in Brussels said, according to AFP, that resources “could be reduced and then shifted, either to increase the readiness of the force in the continental US or shifted to the Pacific.”

At the same time, international competitors such as China, Russia, India, Turkey and countries of the Middle East are hot on their heels. For example, in 2017, the share of France in exports to the African market decreased to 5.5% from 11% in 2000, while China’s shares increased from 3% to 18%. As for Turkey, Erdogan has been active in the region since the late 1990s, and after considerable investments and humanitarian aid, Ankara has become interested in developing a military presence on the continent, which has naturally deeply upset the French.

Article de la revue américaine Quartz sur notre combat contre le neocolonialisme. Plus ils nous attaquent plus le monde entier comprend ce que l'on fait. https://t.co/OsKOZG8kjh

— Kemi Seba Officiel (@KemiSeba1) January 9, 2020

Macron has been unable to simultaneously promote his image of a liberator-decolonizer and continue to serve European bankers by using Africa as a resource base. While Macron may prefer colonialism with a handsome democratic face, destabilization and increasing violence are more and more often accompanied by anti-French slogans, suggesting that Africans will no longer tolerate Paris’s interference. At least not for long.

It is unlikely that Africa will achieve liberation in the coming years, but things are beginning to change. It is crucial to keep in mind, however, that only the Africans themselves can liberate Africa, and they will do so when they are ready and well supported by other countries, and when their rulers are no longer afraid of Washington or Paris’ reactions. However, according to Mustafa Efe, President of the African Centre for Strategic Studies (AFSAM) for the time being, Africans continue to live on a continent which belongs to Europe.

Leave a Reply