US foreign policy can almost be summarized in the fact that the country has 600 military bases around the world and Washington’s astronomical annual funding for both warfare and “soft power” efforts. Despite how incredibly concerned their leadership evidently is with the issue, Americans, for the most part, have little interest in foreign policy. If anything there is a penchant toward self-isolation or the “Monroe Doctrine,” which accompanies the slogan “America is for Americans,” religating the entire world outside beyond the border as hardly worth the attention. This has particularly been the case since Donald Trump became president, after which even traditionally anti-war sections of US society (such as students) have become increasingly concerned with domestic issues.

Trump’s presidency has been severely criticized both by opponents and many of the president’s Republican colleagues, primarily because Washington’s reach into the international arena seem almost absolute, while at the same time remaining remarkably limited. How is this possible? This problem has been exacerbated by Congress’ hostility toward the administration, a situation which became far more acute after the opposition Democrats won the majority of seats earlier in the year. It’s important to keep in mind the fact that, in the State Department itself, many Democratic officials are still present in leading posts, having been appointed by Trump’s predecessor Barack Obama.

As a result, US foreign policy has developed an orientation that is as paradoxical as it is unprecedented. On the one hand, the conductor of the country’s “realpolitik” in the international arena is still officially the president. However, hostile Congress regularly blocks key foreign policy decisions. Since Congress is responsible for managing the state budget, the president is held back from many “significant gestures,” unable to win approval from lawmakers on Capitol Hill. The house is undoubtedly divided, but will it fall?

Who really decides US foreign policy?

Some argue that true architects of US foreign policy are the chair of the House’s Foreign Relations Committees, Eliot Angel, and the Senate’s James Riesch. It is not surprising that their influence at the moment is far more significant than the opinion of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo or the former Assistant to the President for National Security John Bolton when it comes to important and fundamental issues. As the ambassadors of several countries have pointed out, it is much more important for them to meet with congressmen to find out exactly what America has in mind, rather than wait for the next Tweet from the White House. This is particularly the case given that the president’s policies can change dramatically within a couple of hours.

Wikimedia Commons

The State Department also has its own foreign policy angle. It has been particularly energetic advancing its idiosyncratic interests since the neocon Pompeo took office. Pompeo is a hubristic and obstinate politician who is not averse to “pulling the blanket of foreign policy” solely over himself. His gusto for foreign intervention makes the state department a more critical actor than it was designed to be (Pompeo’s intense personal desire to overthrow the government of Venezuela is a good example).

While not quite as overtly influential as it once was, the Pentagon is also pushing its line and vision for US foreign policy. It is the military that determines how to present a particular military operation to the president, as well as what is already being carried out and what is still being planned. Since Trump loves the army and green lights essentially everything they propose, the military elite of America has begun to be included in most important foreign policy decisions.

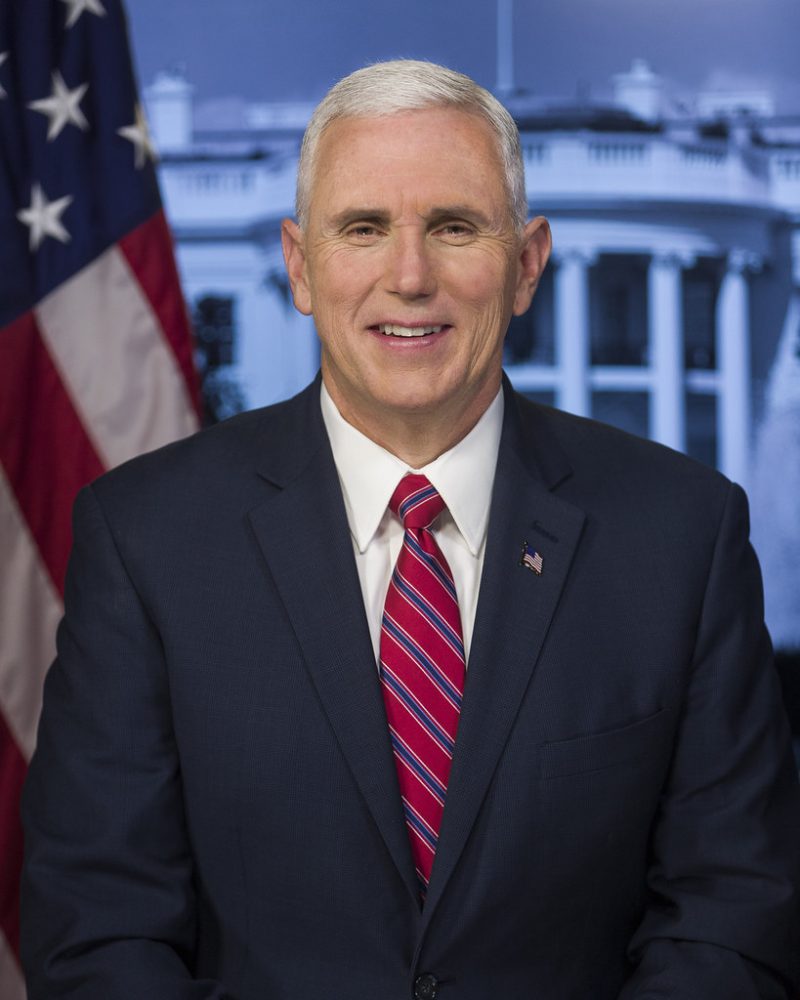

On the other hand there is the CIA, the National Security Council (formerly under the leadership of the hawkish Bolton) and finally, ex-Vice President Michael Pence, who has a unique vision for a whole range of US foreign policy guidelines (for example, in terms of US relations with Russia, Iran and the former Soviet republics). The CIA and the president don’t always see eye to eye when it comes to international relations, leading to a number of situations where the CIA does what it thinks is best for the country of its own accord. It is hardly accidental that it was a CIA officer who “turned in” Trump regarding his conversation with the Ukranian president, resulting in the Democrats opening an impeachment investigation.

Despite these internal divisions, it is crucial to note that this “multi-stationed” American foreign policy nonetheless remains united in pressing toward globalism and opposing its competitors’ efforts to achieve multipolarism.

An absence of strategy?

Two very important components of US foreign policy in the past have disappeared in recent times. The first is strategic planning, i.e., a vision of problems in the long term… as opposed to only looking a few months out. The second is systematic coordination between the departments and structures that work outside America’s borders.

“We do not know what we want, but they do not know what to expect from us,” complained one American diplomat regarding Trump’s meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. “And this means that during the second summit, both leaders will at best agree on a third meeting… but no more than that. Moreover, no matter what our president thinks and promises at such a meeting, he will still be forced to obtain permission from Congress for any of his actions. And there today he is not particularly welcome. Therefore, the North Korean leader is likely to offer nothing to the US president. Because he knows that not everything depends on that. ”

Over the past two years, numerous departments and organizations working abroad have noted more “inconsistencies” in the foreign policy arena. Everyone is trying to win a certain “local battle”, to complete short-term tasks in order to justify the allocation of a higher budget for themselves.

How long will the multi-vector nature of American foreign policy last? Apparently, at least until the end of the mandate of the current White House administration. At the same time, it remains impossible to predict whose foreign policy strategy will actually be implemented and which ones end up playing an auxiliary role or simply distracting attention from the most important and essential moves the country is making. At moments two strategies are both implemented which directly seem to contradict one another, such as when Washington was simultaneously arming and bombing the same radical Islamic groups in Syria. Looking at the chaos of that situation, it appears the left hand often knows not what the right hand is doing.

From another point of view, the neoconservative strategy of widening US military reach to spread “democracy” is still in effect: the Sudanese revolution was supported by American diplomats and Soros-linked structures, the protests in Lebanon are signal-boosted in the globalist media, American special forces are bound to continue to maintain strategic instability in Iraq. In general, soft power outlets seem to remain untouched by the chaos, whereas extra-military economic attacks such as sanctions are dramatically increasing.

Trump: indecision or inability?

Despite that Trump’s promise to lean toward isolationism in his foreign policy proved popular with voters, his time an office has indicated that he is either unable or unwilling to make any dramatic gestures in that direction. Much like Obama’s empty promises of removing American troops from Afghanistan, Trump has been doing little more than shuffling the deck when it comes to US interference in the Middle East. While Trump suggests he is going to allow foreign leaders to decide their own affairs in one breath, in the next he often suggests that full-scale invasion is still on the table (such as in relation to Venezuela or Iran). The president’s efforts to ride the fence on foreign policy have proven confusing to voters at home and political leaders abroad.

While it is unclear to what degree Trump is simply unable to realize his vision due to the pressure from other offices, gestures such as firing Bolton seem to suggest he is at least attempting to foster a more tempered approach. At the same time, it is all too evident that those with a vested interest in war still have the president’s ear.

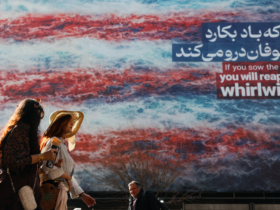

Flickr

One example of pro-war forces profoundly affecting the US’ decision-making process is foreign government lobbying, and in particular, the Israeli lobby. Organizations like AIPAC spend millions of dollars, far more than any other interest group, pushing US lawmakers to advance Israeli interests in the international sphere. Israel has been particularly interested in getting the US to help in its fight against regional competitor Iran. Looking at the US’ punishing sanctions regime and proximity to all-out conflict with Tehran in the Persian Gulf over the last year, it is clear these lobbyists are getting their money’s worth.

The intersection of all of these interests on the largest army in the world has led to a considerable degree of chaos and inefficiency, yet, at the same time, it seems that no force can fundamentally shift the country away from its imperialist and interventionist orientation. Unfortunately, it seems that the predominantly isolationist population of the US has the least amount of influence when it comes to their country’s foreign policy decisions.

Leave a Reply