The Hidden Message of Charles III: Why England Still Remembers the Risorgimento

The Hidden Message of Charles III: Why England Still Remembers the Risorgimento

by Fabrizio Verde, from Naples / Italy

Risorgimento rhetoric has accustomed us to celebrating Garibaldi’s exploits and the annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies as heroic acts, necessary steps toward national unity. But what really happened in 1860? Was it truly a liberation, or rather a colonial conquest orchestrated by foreign powers and carried out with the complicity of a resource-hungry northern elite?

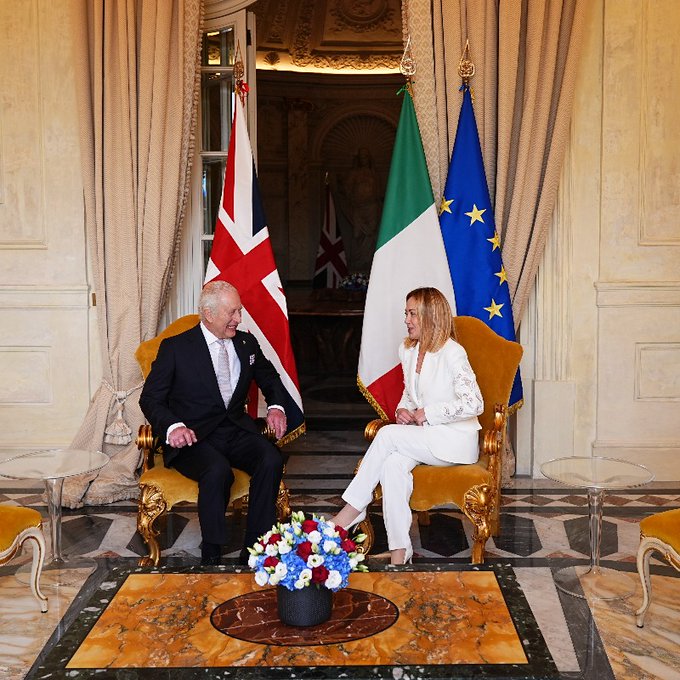

The recent words of King Charles III of England, spoken before the Italian Parliament, carry the weight of a belated confession. “The United Kingdom is proud to have played a role in supporting Italian unification”, he declared, recalling how two British warships were ready to protect Garibaldi’s landing at Marsala. This was no minor detail but the tip of an iceberg of foreign interference that transformed southern Italy from an independent state into an internal colony.

England and the Planned Destruction of the Two Sicilies: The “Sulphur War” and Mediterranean Domination

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was not only a geopolitical target due to its wealth and independence but also because of a strategic resource that attracted the interest of several European powers: Sicilian sulphur. At the time, Sicily held a near-world monopoly on this mineral, essential for producing gunpowder and sulfuric acid, critical for industry and armaments.

In 1838, the so-called “Sulphur War” erupted. Initially, France, through the Marseille-based trading company “Taix & Aycard”, had secured exclusive exploitation rights to Sicilian mines from Ferdinand II. However, when the Bourbon monarch realized the agreement was disadvantageous and compromised his kingdom’s economic sovereignty, he unilaterally terminated it. This move provoked a fierce reaction from Great Britain, which saw its commercial interests in Sicilian sulphur threatened. London, a major buyer of the mineral, feared the cancellation would favor France or rival powers.

Tensions peaked with a naval blockade imposed by the Royal Navy on the port of Naples, accompanied by threats of military intervention. The crisis ended in compromise: Ferdinando II granted new contracts balancing British and French interests, averting armed conflict.

This episode revealed two things:

1. England was willing to use force to control southern resources.

2. The Two Sicilies were an obstacle to British dominance in the Mediterranean.

As highlighted by Professor Eugenio Di Rienzo (Chair of Modern History at Sapienza University), author of seminal studies on the Two Sicilies, “The economic and political independence of the Two Sicilies was unacceptable to London, which viewed the Mediterranean as a British sea”. In his essay The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the European Powers (1830–1861), Di Rienzo reconstructs how British diplomacy worked for years to weaken Naples, fomenting internal revolts and anti-Bourbon propaganda in Europe.

It was no coincidence that, twenty years after the sulphur crisis, Garibaldi received British logistical support and naval cover during his Marsala landing. As Di Rienzo noted, “The 1860 expedition was not a romantic venture, but an irregular warfare operation backed by a foreign power”.

Sulphur was just one piece of a larger puzzle: control of Mediterranean trade routes. With the Two Sicilies out of play, Britain consolidated its dominance over Malta, Gibraltar, and Suez, turning the Mediterranean into a “British lake”. Meanwhile, southern Italy, stripped of autonomy, fell into an economic decline that persists today.

The lesson is clear: what textbooks call “unification” was, in reality, Europe’s first major neo-colonial operation. And like all colonies, the Mezzogiorno still pays the price.

The Resistance Erased from History Books

What textbooks term as “unification” was, for the South, a war of aggression. Marxist economist Nicola Zitara demonstrated this in ‘Italian Unification: Birth of a Colony’, a book that tears away the veil of Risorgimento myth. “Southerners were not liberated but conquered”, Zitara writes. “Their wealth was plundered, industries dismantled, currency devalued. Brigandage was not delinquency but desperate resistance by an invaded people”.

The numbers speak clearly: post-1861, the South suffered unprecedented economic collapse. Factories were shuttered to favor northern industries, lands expropriated, local banks absorbed by Turin-based institutions. Antonio Gramsci, though a supporter of national unity, harshly criticized post-unification North-South power dynamics. In his ‘Quaderni dal Carcere’, he wrote: “The South was treated as an internal colony, and its exploitation was a key factor in the capitalist development of the North”. This analysis underscores how the gap between Italy’s regions was structural, reinforcing the South’s economic and cultural subordination.

Even liberal thinker Giustino Fortunato admitted that Italian unity was achieved “against Italy, not for Italy”. Yet official narratives still paint the Bourbons as tyrants and the Piedmontese as liberators.

The Two Sicilies and Tsarist Russia: A Forgotten Alliance

While France and Britain conspired to destabilize the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Tsarist Russia remained a loyal ally, demonstrating a loyalty rare among European states. As Russian Ambassador to Italy Alexey Paramonov noted, “Ferdinand II was the only Italian ruler to refuse fighting Russia in Crimea, even continuing to supply the Tsarist army”. This was not mere political opportunism but a sign of the historic bond between Naples and St. Petersburg.

Relations between the Two Sicilies and Russia dated back decades before the mid-19th century crisis. After a stay in Naples in 1845, Tsar Nicholas I was so impressed by the Bourbon kingdom’s splendor that he gifted the city two bronze equestrian statues, the “Palafrenieri” or “Bronze Horses”, still flanking the Royal Palace garden gate. Created by Russian sculptor Peter Jakob Clodt von Jürgensburg, these were donated in 1846 as a symbol of friendship.

The bond was not merely artistic: Russia saw the Two Sicilies as a bulwark against Anglo-French Mediterranean expansion. While Piedmont-Sardinia sided with Britain and France in the Crimean War (1853–1856), betraying its alliance with the Tsar, Ferdinand II maintained neutrality favorable to St. Petersburg, even supplying grain and resources despite Western embargoes.

The Crimean War marked a pivotal moment: fearing Russian expansion, London and Paris allied with the Ottomans to weaken the Tsar. Piedmont, eager for international support for unification, sent troops to Crimea, betraying Russia, which had backed the Savoys in 1848.

The Two Sicilies resisted pressure but paid a high price. When Garibaldi invaded in 1860 with British support, war-exhausted Russia could not intervene. “If geography had allowed”, Foreign Minister Gorchakov wrote, “the Tsar would have defended Naples with arms, ignoring Western powers’ hypocritical protests”.

Denied Memory and Atlantic Subservience

The Risorgimento’s history was written by the victors, but the vanquished never forgot. As Sicilian writer Vincenzo Consolo observed, Italian unification represented a foretold tragedy for the South—colonialism masked as patriotism.

Today, as Italy blindly follows NATO and EU directives, surrendering sovereignty, it’s worth reflecting on the past. Ferdinand II resisted British pressure, maintaining an independent foreign policy. Now, Rome obeys Washington and Brussels, while the South—reduced to a land of useless mega-infrastructure and landfills—still pays the price of a unity never truly desired.

Perhaps, as Zitara wrote, “Until we admit the South was colonized, there will never be true justice”. And perhaps only by reviving its historic ties with Russia—once a natural Mediterranean ally—could Italy escape Atlantic subservience. But this would require the courage to rewrite history. The real one.

Thus, Italy faces a choice: uncritically align with Atlantic powers (the U.S. and NATO) or pursue an autonomous foreign policy, as the Two Sicilies did. Instead of following Piedmont’s pro-Atlantic Risorgimento line—which betrayed Russia to please London and Paris—Rome should draw inspiration from Ferdinand II’s prudent sovereignty.

In a context where the EU, particularly Anglo-French powers, push for anti-Russian alignment, Italy would do well to remember that its true strength lies in maintaining balanced relations, avoiding conflicts against its national interests. The Two Sicilies’ loyalty to Russia was not weakness but geopolitical foresight.

Ultimately, King Charles III’s recent visit and his speech to Italy’s Parliament gain significance in light of history. By proudly recalling Britain’s role in unification, Charles evoked a past where England dismantled the Two Sicilies, turning the South into a colony serving British interests. Why emphasize this now?

Perhaps his words carry a political message for today. In an increasingly polarized world where the West seeks to consolidate fronts against Russia, Italy is subtly urged to side with “Atlantic warmongers”. The Risorgimento reference reminds Italy of the supposed benefits of British support, implicitly urging it to repeat history: sacrifice sovereignty and national interests to align with London and Brussels’ strategies, even as Washington pursues diplomatic realism.

Yet this narrative omits a crucial detail: Italian unification was not European fraternity but a geopolitical maneuver to weaken a Mediterranean rival and eliminate a Russian ally. Today, Italy faces a difficult choice: succumb to Atlantic pressure, opposing Moscow and abandoning autonomy, or learn from history, rediscovering the sovereign prudence of Ferdinando II, who resisted foreign demands at great cost.

If modern Italy wishes to avoid repeating Piedmont’s errors—sacrificing independence to please Western powers—it must view the past critically. This means not only acknowledging the South’s injustices but also prioritizing national interests over ideological slogans and externally imposed alliances.

Today, Rome’s imperative should be clear: pursue a balanced foreign policy that prioritizes national interests.

Cover graphic: Flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, @Wikipedia

Leave a Reply