By Michael Roberts *

After almost two full years of war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused staggering losses to Ukraine’s people and economy. Ukraine’s GDP fell by 40% in 2022. There was a small recovery in 2023, but an additional 7.1 million Ukrainians now live in poverty.

There are various estimates of the number of Ukrainian civilians and military casualties after two years of war. The UN estimates about 10,400 civilian deaths with another 19,000 wounded. The military casualties are even more difficult to estimate – but probably about 70,000 soldiers killed and another 100,000 wounded. Russian military casualties are about the same. Millions have fled abroad and many more millions have been displaced from their homes within Ukraine.

When I reviewed the economic and social state of Ukraine and Russia one year into war in 2023, I concluded that both sides would be able to continue this war for years, if necessary. For Ukraine, that depended on getting aid (civil and military) from the West. For Russia, it meant continuing to obtain sufficient export revenues from its energy and resources commodities.

Russia could not rely on foreign financing to fund the war, but I reckoned that it could carry on in the face of economic sanctions from the West, as long as its energy revenues and its FX reserves were not depleted too much; or its domestic economy did not contract so much that it caused social unrest within Russia. And so it has proved. The Russian economy is stable, the war effort is being sustained and Putin will win a new presidential term next month.

Ukraine is still totally dependent on support from the West. This year it needs at least $40bn in order to sustain government services, support its population and maintain production. It is relying on the EU for such civil funding, while relying on the US for all its military funding – a straight ‘division of labour’.

In addition, the IMF and World Bank have offered monetary assistance but, in this case, Ukraine has to show it has ‘sustainability’, i.e. it is able at some point to pay back any loans. So if the bilateral loans from the US and EU countries (and it is mainly loans, not outright aid) do not materialise, then the IMF cannot extend its lending programme.

Moreover, Ukraine also needs to find a way to restructure about $20 billion in international debt this year with sovereign bondholders whose agreed two-year payment freeze made in August 2022 will be up soon.

And it is a struggle. Despite some recovery in exports, Ukraine’s balance of trade deficit continues to worsen.

That means that the foreign exchange coffers to buy imports disappear nearly as fast as they are supplemented by Western aid.

Ukraine Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko said the government hoped to secure foreign financing in full in 2024, but if the war lasted longer, he added ominously that “the scenario will include the need to adapt to new conditions.”

Presumably that would mean either cuts in services or getting Ukraine’s central bank to just ‘print’ money. The former would mean more poverty and a further contraction in living standards; the latter would mean a renewal of an inflationary spiral into double-digits (inflation had fallen back in 2023). It seems that the Ukrainian government expects either the loans to come through or the war to end in 2024. The former may happen, the latter is unlikely.

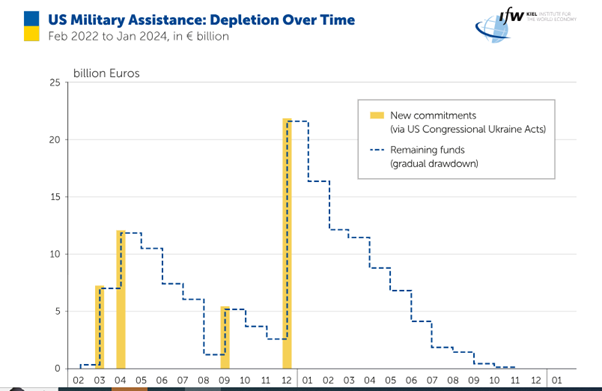

But will the aid to drip feed Ukraine’s economy in 2024 come through? Europe is delivering funds for civilian activities, but it’s up to the US to deliver funds for military activities. The last remaining funds for US military assistance were depleted by end-2023. In total the US has allocated around €43 billion in military aid since February 2022, which is about €2 billion per month.

US funding for the Ukraine military remains unclear as the US Congress is divided over providing further military aid. The upcoming presidential election, with the possibility of the return of Trump in 2025, poses the major uncertainty.

That brings us back to what will happen to Ukraine’s economy, if and when the war with Russia comes to an end. According to the latest estimate of the World Bank, Ukraine will need $486bn over the next ten years to recover and rebuild – assuming the war ends this year. That’s nearly three times its current GDP.

Direct damages from the war have now reached almost $152 billion, with about 2 million housing units – about 10% of the total housing stock of Ukraine – either damaged or destroyed, as well as 8,400 km (5,220 miles) of motorways, highways, and other national roads, and nearly 300 bridges. As of December 2023, about 5.9 million Ukrainians remained displaced outside of the country and internally displaced persons were around 3.7 million.

And as I explained in a previous post back in mid-2022, already what is left of Ukraine’s resources (those not annexed by Russia) are being sold off to Western companies. For example, the sale of land to foreigners was approved in 2021 under IMF pressure and now the food monopolies Cargill, Monsanto and Dupont own 40% of Ukraine’s arable land. GMA-Monsanto Corporation owns 78% of the land fund of Sumy region, 56% of Chernihiv, 59% of Kherson and 47% of Mykolaiv region.

Overall, 28% of Ukraine’s arable land is owned by a mixture of Ukrainian oligarchs, European and North American corporations, as well as the sovereign wealth fund of Saudi Arabia. Nestle has invested $46 million in a new facility in western Volyn region while German drugs-to-pesticides giant Bayer plans to invest 60 million euros in corn seed production in central Zhytomyr region.

MHP, Ukraine’s biggest poultry company, is owned by a former adviser to Ukrainian president Poroshenko. MHP has received more than one-fifth of all the lending from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in the past two years. MHP employs 28,000 people and controls about 360,000 hectares of land in Ukraine — an area bigger than EU member Luxembourg. It had $2.64bn in revenues in 2022.

The Ukrainian government is committed to a ‘free market’ solution for the post-war economy that would include further rounds of labour-market deregulation below even EU minimum labour standards i.e sweat shop conditions; and cuts in corporate and income taxes to the bone; along with full privatisation of remaining state assets. However, the pressures of a war economy have forced the government to put these policies on the back burner for now, with military demands dominating.

What about Russia? After two years since the invasion, it is clear that the sanctions introduced by Western governments to weaken Russia’s ability to continue the invasion have failed. Russia’s economy is growing, even if that growth is mainly based on production for the military sector. Energy prices and export revenues have remained strong with sales to third parties like China and India comfortably replacing export losses to Europe. According to official figures, 49 percent of European exports to Russia and 58 percent of Russian imports are under sanctions, but the Russian economy still grew 5% in 2023 and will grow further this year.

Yes, $330bn of Russia’s FX reserves have been seized by the West, but Russia’s FX coffers remain more than sufficient. The cost of pursuing the war remains huge, with 40% of the government budget, but funding is still sufficient without resorting to money printing or to cutting civilian services.

In many areas, Russia is self-sufficient in critical commodities like oil, natural gas, and wheat, which has helped it weather the years of sanctions. Russia can also supply itself with most of its defence needs, even for sophisticated weapons. So it can continue this war for many more years, even if that damages the long-term potential of the economy.

In contrast to Ukraine, the Putin regime aims for a more state-controlled economy, where the big companies work in close coordination with Putin’s cronies. But similar to Ukraine, corruption between oligarchs and government will continue. Meanwhile the war grinds on.

* Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. At the same time, he was a political activist in the labour movement for decades. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.

This article was previously published on Roberts’ blog here.

Leave a Reply