by Yiğit Saner / Rome, Italy

When new evidence emerges about a historical topic or when there is a need to reevaluate our existing knowledge, reconsidering – without any ideological influence – what we know about history can become an example of positive and necessary historical revisionism. However, that’s not always the case. Revisionism deals with the issues that go back to history, to events that happened hundreds, thousands of years ago, and this makes it extremely open to manipulation. Those interested in this other side of revisionism need little evidence or objectivity. This approach ignores, devalues, distorts and in some cases completely rejects the historical facts that have been proven with documents for political/ideological purposes.

A typical example of negative historical revisionism for propagadistic purposes recently appeared in a speech by the Italian Deputy Foreign Minister Edmondo Cirielli. His definition of Italian colonialism as a “Civilizing culture” aroused a great reaction especially in the circles which embraced partisan culture. And thanks to the Deputy Minister, people have the opportunity to reflect on Italian colonialism, which was partially obscured by politicians and interest groups to preserve the delicate balances that emerged in Europe and in Italy after the World War II, and therefore little known and little discussed but it’s worthwhile to remember.

Nostalgia in the Mussolinian City

To better understand the context, I would like to point out first of all that the meeting where Cirielli spoke was organized by Gioventu’ Nazionale (National Youth), the youth section of the Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), the party of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, and it occured in a place of high symbolic value: EUR (Esposizione Universale di Roma – Universal Exposition Rome), a district of Rome.

EUR’s (ex E42) construction began in the second half of the 30’s at the request of Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945) and was established in the Tre Fontane area, south-east of Rome, to glorify the Fascist regime and its Empire in Africa. EUR had on the one hand to return the splendor of the ancient Empire to the city of Rome projecting it into the future and on the other dressing it with a rational, neoclassical, linear and geometric architectural style to be the symbol of the new Fascist Italy. In fact, “the competition notice (for the design of EUR) asked that ‘the architectures express a classic and monumental feeling’”[i] So it is no coincidence that one of the best-known exponents of Fascist architecture, known as the greatest ideologist of the Regime’s monumentalism, Marcello Piacentini (1881 – 1960), was chosen to coordinate the project. This was the city dreamed by the Duce: Mussolinian City.

Now that the scenography is ready let’s look at Cirielli’s speech suggesting that Italian colonialism had civilized Africa, that the settlers built roads, bridges, infrastructures in exchange for raw materials, and that this trading system will continue today by revoking the Piano Mattei[ii] (Mattei Plan). What the speech does not suggest, of course, are the war crimes committed by the fascist hierarchs in Africa, the exploitative order established by them, the practices of apartheid and other delicts:

“The Italian has always been a person who respects others, I say this without raving. Italians, both in the pre-fascism period and during fascism, the Italian government, Italy in its one hundred years of colonies in Africa has built and implemented a civilizing culture. We are not by nature people who go to plunder and steal from others. Our ancient culture doesn’t make us a people of pirates who go around plundering the world. We, on the other hand, have a civilizing culture. Africa is a nation of raw materials, we as Europeans have always taken and want to continue taking. Only that Italy, Giorgia Meloni, with the Mattei Plan claims that if we take raw materials from that people we must leave something for the future generations that will arrive: roads, ports, industrial areas, schools, hospitals, because we take gold, uranium, iron, oil, gas and other things.”[iii]

The reaction of the Partito della Rifondazione Comunista (Communist Refoundation Party), which is positioned against the mainstream even in the Ukraine-Russia war unlike the European left, whose majority now follows the American Democrats, was quick and harsh:

“It is not acceptable for a Deputy Minister of the Republic to define, like Mussolini, that of Italian colonialism as a ‘civilizing culture’ or to re-propose the false narrative about the “good Italians” who have not plundered and robbed the colonized peoples.

Fascist Italy has committed crimes against humanity in Africa, including the use of chemical weapons, which unfortunately continue to be removed from national memory. Those of the deputy minister are words incompatible with the principles of our Constitution and above all unworthy of a democratic country. We demand the immediate resignation of the minister who dishonors the Republic and cannot be justified in any way.

Cirielli’s words show how offensive the exploitation by the neo-fascists of the name of the partisan Enrico Mattei who financed the anti-colonialist movements with Eni.

We will also bring this case, through our group The Left, to the attention of the European Parliament. We must oppose the normalization of neo-fascism in Europe. The neo-fascist flame party was hastily cleared through customs, like the Azov battalion, because it was a faithful executor of NATO orders.”[iv]

The modernization at all costs

What the Deputy Minister tries to do is an attempt to complete a precise rewriting not only of the historical facts, but of the meaning itself of what colonialism is and what colonialism stands for.

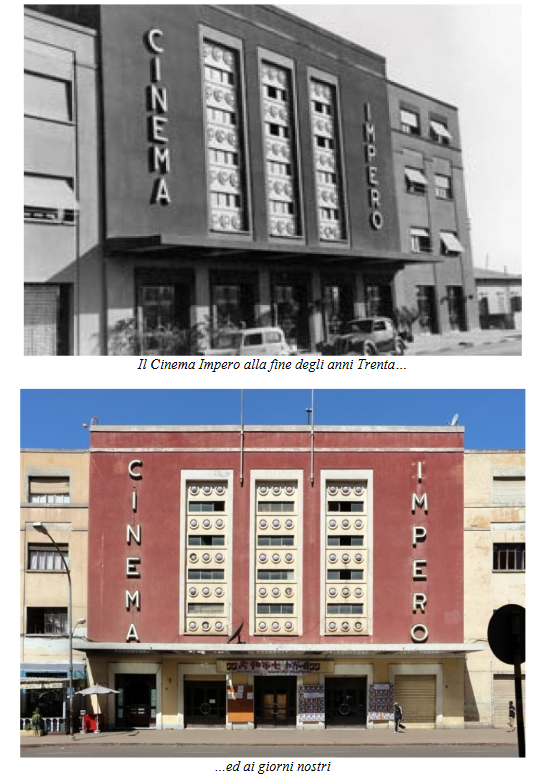

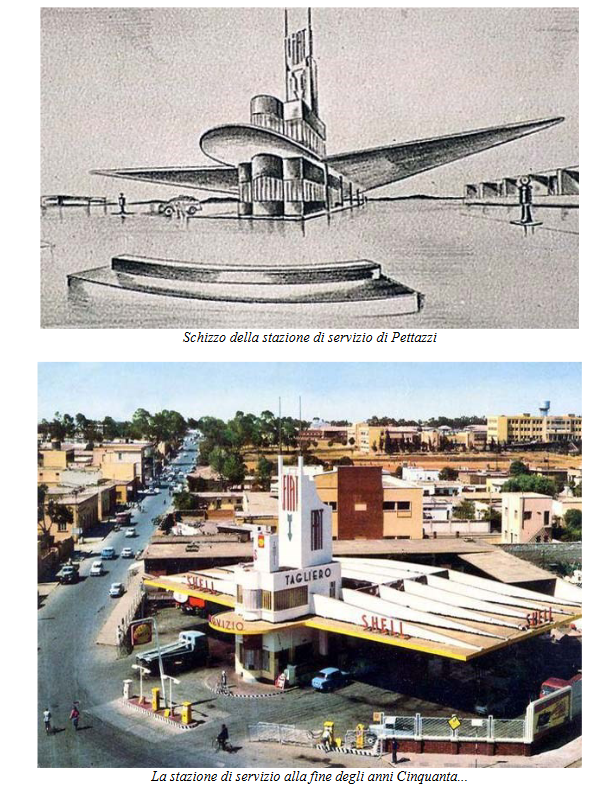

Furthermore, it is absolutely true that the settlers built roads, schools, theaters, leaving behind important works and for this risking economic failure: “For these lands and these colonies, Italy spent staggering sums, counting its possibilities and the continuous expenses for war needs, risking being sucked into its colonies. […] Hundreds of millions, then they were shocking figures, have been spent to extract, transport by sea (passing through the Suez Canal, controlled by England) and then use marble, stone, concrete and other materials both in war and in peace. […] All to build great works out of nothing, the first to appear in those lands. […] New buildings, roads, hospitals, houses no longer made of straw and mud but of cement and lime were built. This rapid urbanization had the dual purpose of organizing the new colonies to be able to start immediately with the self-management of these lands in order to depend less and less on the motherland and the more purely propaganda one of bringing out the power and style of the winners.”[v] , we read on the pages of Qattara where it’s possible to see many images of the buildings built by the colonialists.

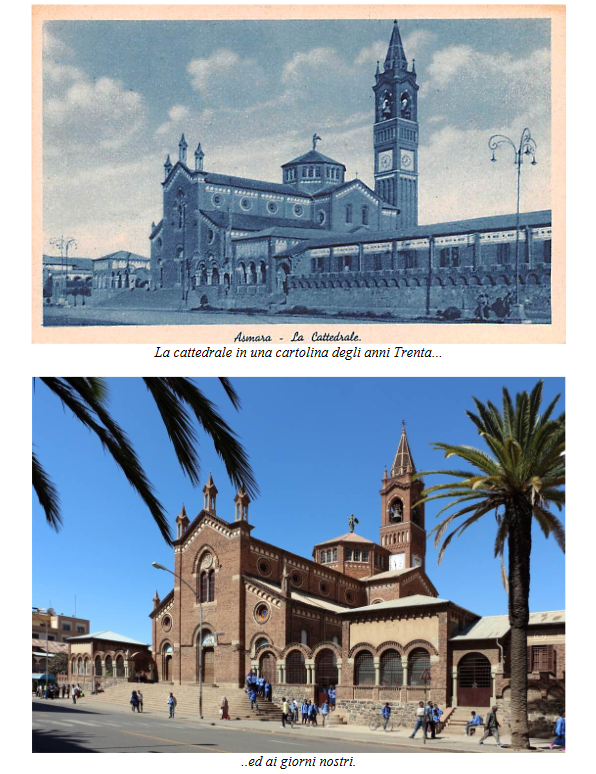

Right: Asmara Cathedral, built in 1923

But the construction of the infrastructures referred to by this article or by Cirielli also represents a murky past of violence. Furthermore, the works that emerged with the modernization of the colonies were built, first of all, to attract Italians to migrate to colonizing countries and to make their lives easier there, to be able to trade, and to allow soldiers to easily fulfill their strategic tasks such as logistics or deployments; or rather, these works that negative historical revisionism loves so much to glorify by ignoring the dark face of colonialism were not made for Africans nor could Africans use them as much as the colonialists, as absorbed by the journalist Erika Farris: “In the capital Asmara (Eritrea), the Italians also created the first apartheid experiment in history, long before South Africa. The center of the city was called Campo Cintato (Fenced Field) and was totally reserved for Italians. In their bars, restaurants and schools, Eritreans were forbidden to enter, and in the buses they had to sit in the back seats.”[vi]

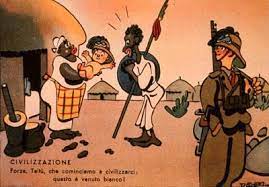

“Behind that concept of ‘civilizing culture’ to which Deputy Minister Cirielli appealed, there is a precise political vision which accepts the exploitation of the resources of other territories to the detriment of their autonomous development, a vision which sees the other as incapable without the Western guide to self-determination.”[vii] Infact, praise of Edmondo Cirielli on “Civilizing culture” in front of the youngsters of the Fratelli d’Italia or Benito Mussolini’s “Civilizing mission” as an excuse for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 or even the profound wisdom of George W. Bush to bring “Democracy and Freedom” to Iraq in 2003 are all problematical manifestations of a perspective that takes responsibility for civilizing at all costs (!) the uncivilized through a civilizing culture.

What colonialism stands for

The Kingdom of Italy, which concluded its political union (1861) later than the other European powers, remained behind in the colonial and modernization race that dragged Europe into the World War I. Regions with scarce resources and population were left to Italy. It was a period, as noted by Nicola Labanca, a historian at the University of Siena, when “having colonies was seen as a way of being modern.”[viii]

Eritrea was the first African country colonized by Italy in 1882, followed by Somalia in 1889. Troops were also deployed to Ethiopia during this period, but with the unexpected defeat at the Battle of Adua in 1896, this attempt failed. Nevertheless, this would not be the last time the Italian colonialists would come to Ethiopia – they would return exactly forty years later with far more modern, far more destructive weapons under the steely will of the Fascist regime.

Anyway, there was still one country that the Kingdom of Italy had to occupy before the baton is handed over to Mussolini in 1922: Libya, taken from the Ottoman Empire in 1912 after the Italo-Turkish War (known also as Tripolitanian War), in which Rodolfo Graziani (1882 – 1955) also participated, the general and fascist hierarch who would later sign bloody massacres in African colonies. But we will talk about the General later.

With the coming to power of Fascism, on the one hand, the climate began to harden in the previously obtained colonies, on the other hand, Ethiopia was again staked. It was up to Mussolini, who wanted to declare his modern military power to the whole world, to make up for the defeat suffered in 1896 against a militarily weak country, thus saving Italy’s reputation. And so the Duce declared war on Ethiopia in 1935 under the name of “Civilizing mission”. An unprecedented military force was deployed for the campaign, far exceeding those used by Europeans to invade African countries: “In May 1936, 330,000 Italian soldiers, 87,000 askaris, 100,000 militarized Italian workers, 10,000 machine guns, 1,100 cannons, 250 tanks, 90,000 pack and attack quadrupeds, 14,000 vehicles, 350 aircraft were involved. The numbers quoted, although approximate, give the conflict a national and modern character, with a structure far superior to that of traditional wars of colonial expansion.”[ix]

After the conquest of Ethiopia, Mussolini proclaimed from the balcony of Palazzo di Venezia in Rome that “Italy has finally its empire”. The calendars were indicating May 9, 1936 and it was then that the King of Italy, Vittorio Emanuele III di Savoia, added that of Emperor to his titles.

Right: The historical announcement of the Duce in the Corriere della Sera

The regime finally completed the picture by invading Albania in 1939 with a rapid military campaign on the eve of the World War II. The result was an empire of 14 million inhabitants (with Italy 57 million), 4 million square kilometers, ten times the size of Italy itself, to be considered extensive today, but small for that period compared to other colonial states such as the United Kingdom and France.

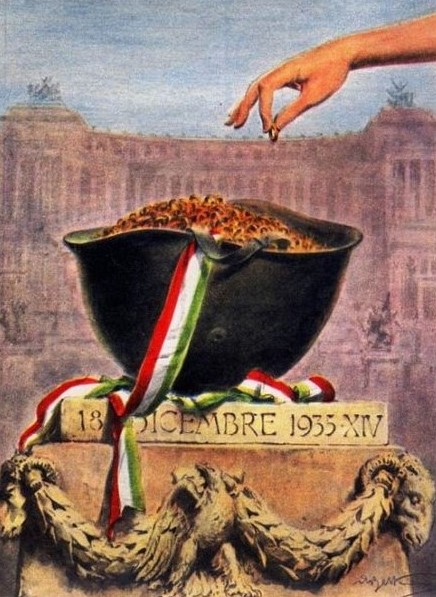

In this period, the Italian economy was deteriorating due to military preparations for the imminent Great War and the maintenance of a vast geography to be “civilised”. It was the League of Nations (which later to become the United Nations) that put salt in the wound: Italy was sanctioned for attacking Ethiopia, a member state. But skyrocketing inflation could not stop Mussolini. The people were under such intense propagandistic activity that Italians for a “right cause” donated 33,622 kilos of gold and 93,473 kilos of silver to the “Oro alla patria”[x] (Gold for the Fatherland) campaign, which was conducted by the Regime using public figures to find easy money. The donor Italians were given a ring made of iron in return for the wedding rings they offered, thus completing their marriage with the Regime.

Right: Women donate their wedding rings

It is also worth mentioning that the campaign was not only supported by ordinary people but among the donors there were also characters of a certain intellectual level such as the great scientist and inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who won the Nobel Prize for physics in 1909 – in recognition of his contribution to the development of wireless telegraphy; the writer and playwright Luigi Pirandello, one of the giants of the 20th century who was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1934 – for his daring and ingenious renewal of dramatic and theatrical art; the great writer, poet and soldier Gabriele D’Annunzio, one of the famous characters of the World War I who became the frontman of decadentism.

So, this was an empire that was built in the space of a few decades in the hands of businessmen looking for new public contracts, soldiers eager to show off Italian modern war power, scientists seeking labs for racist theories, adventurers stunned by propaganda and careerist politicians caught in the wind of extreme nationalism.

Another aspect that should be noted is that the Italians, those dissatisfied with the offers of the homeland, were emigrating intensely to distant lands such as the United States or South America, both before and after Fascism, with the desire to start a new life. In order to prevent this loss of people, the Regime tried to direct the Italians to the colonies instead of America with the promise of job, land or valuable underground resources such as gold and oil.

Right: Volunteers leave for the Horn of Africa

By promoting colonization as a win-win policy, the Regime succeeded partly in spreading its conflicts and achievements in Africa to the Italian people and in promoting civilian migration motivated by the epic Fascist campaign. Despite all these efforts, when the Empire reached its widest limits, the number of Italian civilians living in the colonies was around 300,000, while the number needed by the Regime to establish the desired modern state order and use large agricultural lands was between 500,000 and 1,000,000.

The expansionism is our fate

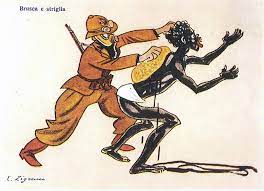

As the 19th century drew to a close, the ideology of racism, which was growing in Europe and beginning to find a social response over time thanks to the expansionist propaganda, constituted a terrain of self-legitimization for all colonial states, and Italy took its share.

The minds of the colonialists who went to Africa with economic motives were filled with racist ideas based on white supremacy. This view, which was based on the need to dominate the local African populations, make them work in hard labor and keep them away from matters such as trade and administration, was extremely common. The Regime also had “scientific” articles published to legitimize its activity in Africa, showing the expansionism of the “superior races” as a necessity.

Right: “Come on, Taitu’, let’s get civilized: This came white”

One of the ardent defenders of this point of view was the anthropologist and explorer Lidio Cipriani (1892 – 1962), who signed the Manifesto of Racist Scientists, published on July 14, 1939. Let’s look at an article that this Florentine anthropologist published in 1932, six years before the approval of the “Racial laws”:

“Generally the Negro impresses by his incorrigible boyish demeanor, by his disposition for childish gaiety and naive pastimes to which no normal White would indulge. He escapes as much as he can from applying his mental faculties, in our way, and his acting is very little by reasoning and much by imitation, especially when transported to live in the bosom of civilization.

Dominated by natural impulses and the pursuit of idleness and individual pleasures, blacks lack any logical-critical capacity and do not conceive the idea of work: rather than building a road or digging a well, the black prefers to abandon himself every day, without worries of any kind, to his favorite pleasures, such as chatting for hours and hours on endlessly repeated silly topics, jumping, making noise and sometimes arguing or amusing himself with his women. Everything else, for any of them, is worth much less.”[xi]

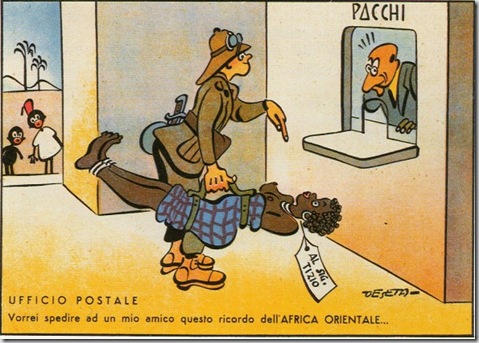

African women were also used in propaganda to attract the attention of mostly male settlers and adventurers. They also were waiting to be freed by the charming princes, the Europeans: “Dominant themes of the propaganda were the civilizing mission towards a barbarian and slave-owning Ethiopia and the expansion of Christian civilization. Above all, the representations revived old stereotypes and legacies of the colonial experience, not only Italian: exotic and mysterious Africa, naive Africans children or cruel savages, the African woman waiting for the civilizing white.”[xii]

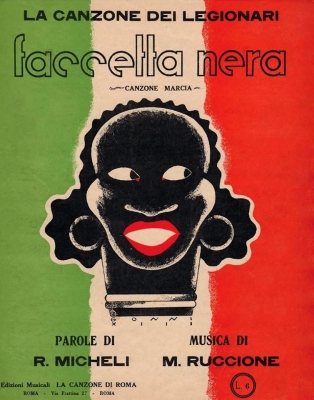

Right: A poster of the song “Faccetta Nera”

Propaganda that Italians actually went to Africa to end slavery was sometimes included in popular songs/hymns of the period. The most famous of these is undoubtedly “Faccetta Nera” (Little Black Face), published in 1935, with lyrics by Renato Micheli and music by Mario Ruccione (1911 – 1969).

In the song written in Roman dialect, a Blackshirt that has gone to a colony promises freedom to African women: “The intent of the song was to extol Italian colonialism in East Africa, exalting the ‘civilizing’ mission of Rome through the reference to the practice of madamato, with which Ethiopian women were actually enslaved by the Italian military and sexually abused.” In fact, the most widespread sexual practice in the Crown of Africa was “the so-called madamato for which the colonialist kept with him, for the period in which he remained in the colony, an African cohabitant-servant, who he used both as a maid and sexually.”[xiii]

Little Black Face (Faccetta Nera)

If you look at the sea from the hills

Young brunette, a slave among slaves

Like in a dream you will see many ships

And a tricolour waving for you

Pretty black face, beautiful Abyssinian

Wait and see, for the hour is coming!

When we are with you

We shall give you another law and another king

Our law is slavery of love

Our motto is FREEDOM and DUTY

We, the Blackshirts, will avenge

the heroes that died to free you!

Pretty black face, beautiful Abyssinian

Wait and see, for the hour is coming!

When we are with you

We shall give you another law and another king

Pretty black face, little Abyssinian

We will take you to Rome, as a freedwoman

You will be kissed by our sun

and a black shirt you too will wear

Pretty black face, you will be Roman

Your only flag will be the Italian one!

We will march together with you

and parade in front of the Duce and the king!

We will march together with you

and parade in front of the Duce and the king![xiv]

In short, as we see so often in the history of the world, women or minors freed from slavery were becoming re-enslaved by their liberators. The practice of madamato, far from being viewed with contempt and often encouraged by the Regime, was banned in 1937 on the eve of the “Racial laws” out of Mussolini’s fear of the emergence of a hybrid race[xv].

Hierarchy, Order, Discipline

The propaganda of white supremacy inevitably fueled exploitation, oppression, and inequality. The increase in violence in the colonies parallels the Regime’s domination of Italy. We can exemplify the climate formed through two different historical cases:

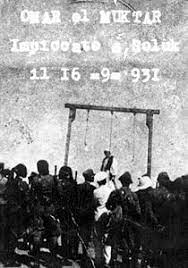

Italy’s colony in North Africa, Libya, had been buzzing with rebellions since the 1920s. In 1930, the Regime sent the General Rodolfo Graziani, later known as “The butcher of Fezzan”, to the region to reclaim the lands lost by the rebels and repress the uprisings once and for all. The brutal, orderly, uncompromising and modern military operations of Graziani, who once called himself “the most fascist of all fascist officers”[xvi], would soon lead to a series of bloody events: from his arrival in Libya to the execution of national hero Omar Mukhtar (1858-1931) and finally the total crushing of the Libyan resistance in 1932.

Right: Execution of Omar Mukhtar

On June 20, 1930, Marshal Pietro Badoglio (1871 – 1956), Governor of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, wrote to the Deputy Governor of Cyrenaica and commander of the Italian forces in Libya, General Rodolfo Graziani: “First of all, it is necessary to create a large territorial gap between rebel formations and a subjugated population. I do not hide the scope and gravity of this provision, which will mean the ruin of the so-called subject population. But by now the way has been traced for us and we must continue it to the end even if the entire population of Cyrenaica were to perish.”[xvii]

“To isolate the guerrillas from the population, (Graziani) opened concentration camps in the desert, deporting hundreds of thousands of members of the nomadic tribes of Cyrenaica, where he exterminated the herds and burned the crops. Few survived the deportations involving old people, women and children, and life in the concentration camps; even less to the use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas, phosgene and arsine which – although already prohibited by international conventions – became the norm in Libya and then in Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia).”[xviii] writes Antonino Adamo of the Italian National Research Council.

In the single repression of the resistance in Cyrenaica where Omar Muhktar was captured “there were, between 1927 and 1931, about 50,000 dead and 100,000 civilians were deported from the Gebel plateau, locked up in camps where the inhuman conditions of imprisonment caused very high mortality.” Historians estimate that more than 100,000 Libyans, mostly civilians, were killed in whole campaign of reconquest[xix].

It may surprise you as much as it once surprised me to learn that “Lion of the Desert”, the 1980 epic historical war film, directed by Moustapha Akkad (1920 – 2005), starring Anthony Quinn (1915 – 2001) as Omar Mukhtar and Oliver Reed (1938 -1999) as Rodolfo Graziani, was banned in Italy in 1982 and was first broadcast on Sky, a private television platform, in honor of Muammar Gaddafi’s (1942 – 2011) official visit in Italy, during the fourth and the last Berlusconi government in 2009.

Right: Oliver Reed as Rodolfo Graziani (on the right)

We now turn to the eastern part of the continent, the Horn of Africa. We have already talked about the gigantic modern war machine that Italy has put in place for the conquest of Ethiopia. In fact, when on 5 May 1936 the Italian troops under the command of Marshal Pietro Badaglio entered the capital Addis Abeda, the military operation was concluded in which chemical weapons were again used: “The fascist air force, in the search for the ‘place in the sun’ desired by Mussolini, unloaded more than 200 tons of explosives, mustard gas bombs and asphyxiant gases (forbidden by international law) against the civilian population in the Battle of Scirè in February-March 1936 alone.”[xx] Now the struggle against the resistance movements would begin.

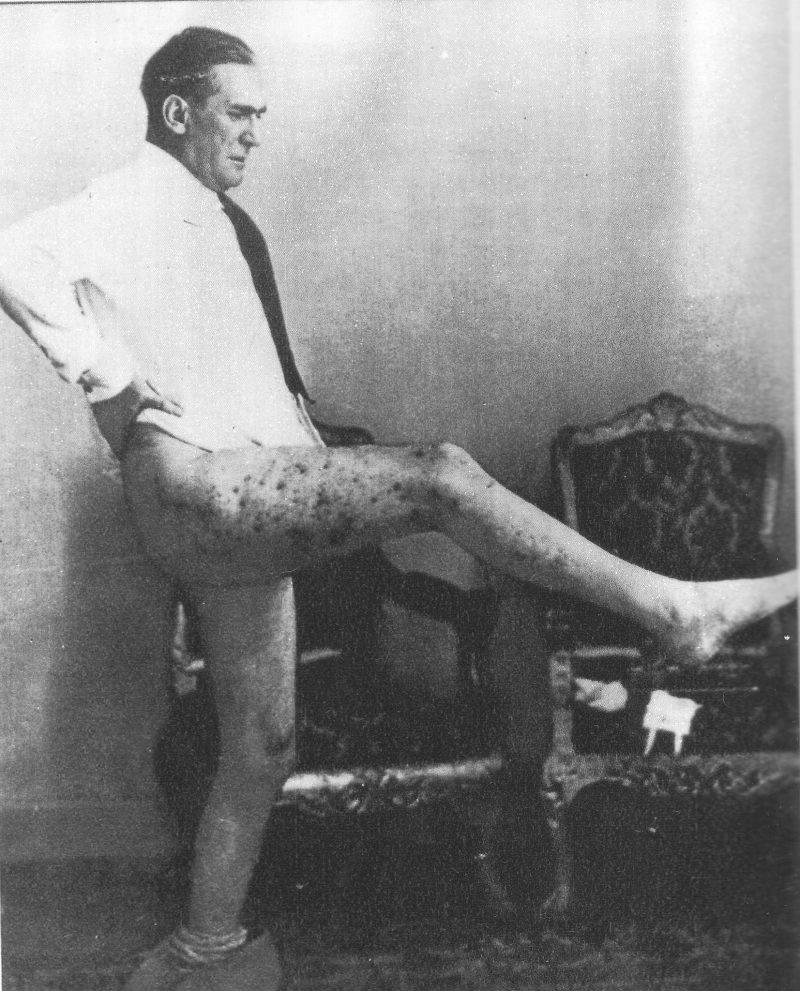

Rodolfo Graziani, who earned the appreciation of the Fascist regime with his activity in Libya, became the Governor General of Ethiopia. On the morning of 19 February 1937, while the birth of the first son of Prince Umberto di Savoia was being celebrated at Palazzo Guennet Leul in the capital Addis Ababa with the participation of representatives of the Italian state, the fascist hierarchs and their Ethiopian collaborators, two young Eritreans from the resistance movement carried out a grenade attack. While Graziani narrowly escaped, fifty of the participants were injured and seven people died.

Right: Graziani shows off his injuries after the attack

The great anger of the Regime would be reflected immediatly in the streets of Addis Ababa on the day of the incident and would last until May 21st:

“The response of the Fascist Regime was brutal. In less than three days the streets of Addis Ababa were stormed by fascist squads: fully armed Italian soldiers and many civilians took to the streets giving life to what Antonio Dordoni, a witness, called ‘a frenzied hunt for the Moor’. In general – we read in the book by the historian Angelo Del Boca – ‘they set fire to tucul with petrol and finished off those who tried to escape the fires with hand grenades’. Not only the Italian soldiers took part in the retaliation but, in a climate of absolute impunity, also traders, drivers, officials and ordinary people who committed violence of all kinds. For every Abyssinian (Ethiopian) in sight – wrote Del Boca – ‘there was no escape in those terrible three days in Addis Ababa, a city of Africans where for a while no more African was seen’.”[xxi]

It is not known exactly how many Ethiopian civilians were killed in the three days of hell. According to historian Angelo Del Boca (1925 – 2021), mentioned in the quote above and who made great efforts to reveal the dark side of Italian colonialism, the death toll is around 3,000[xxii], conforming to another Italian historian, Giorgio Rochat, who has many publications on the subject, this number is between 3,000 and 6,000[xxiii]. It is thought that this number may rise to 19,000 with the massacres that continued in the weeks following the first three days. Ethiopians however claim that 30,000 civilians were killed in this turmoil. Regardless of their number, all victims are commemorated each year on Yekatit 12 (February 19 in the Ethiopian calendar).

Italian colonialism is alleged to have caused the deaths of approximately 1,000,000 Africans for reasons such as wars or deportations[xxiv]. The total exact death toll is still open to debate, as sources are sometimes insufficient and sometimes distorted.

Del Boca vs Montanelli

Since we have made a reference to the historian Del Boca (1925 – 2021), it becomes mandatory to briefly mention the famous case of the journalist and writer Indro Montanelli (1909 – 2001) and speak of his revisionist outing linked to colonialism. The most important development revealed by the Montanelli case is that it provoked a series of declarations which would later end with the admission by the Italian state of some accusations related to colonialism.

In short, the debate began when Del Boca’s claims about colonialism – especially those relating to chemical weapons – were refuted by Indro Montanelli, who had personally witnessed Italian Ethiopia, in the pages of Corriere della Sera in 1995. Montanelli, in fact, was luckier in terms of credibility than Deputy Minister Cirielli, having lived through the colonial period in Ethiopia. However, Del Boca did not step back in these public debates and emphasized once again that the Italian State Archive was the basis of his writings by responding to Montanelli in the Corriere della Sera[xxv].

It was the declaration of the Minister of Defense Domenico Corcione (1929 – 2020) that closed the discussions in 1996, according to this, the Minister “admitted that sixty years earlier in Abyssinia aircraft bombs and artillery shells loaded with mustard gas and arsine had been used, and that the use of the gases was known to Marshal Badoglio. A few weeks ago the text of a telegram from Mussolini had been discovered in which he gave his approval to the use of these weapons, which were prohibited by international conventions.”[xxvi] A year later, then-President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (1918 – 2012) formally apologized for the occupation of Eritrea.

In the last years of his life, in an interview with journalist Gianmarco Aimi, Del Boca was asked for his point of view on Indro Montanelli’s madamato treatment of a 12-year-old Ethiopian girl in the Horn of Africa and on the attacks on the Montanelli monument in the context of the Black Lives Matter protests, and the legendary historian chose to give answers that the journalist did not expect:

“I think it is profoundly stupid and ignorant to pick on the statue of Indro (Montanelli) and also of Christopher Columbus! Statues are symbols of their era and as such they must be respected, i was amazed to read that the statue of Churchill was hit in England by boys who said they didn’t even know who he was.

I have always respected my opponents, especially those who, like Montanelli, had intellectual dignity. In those days, but perhaps still now, it was normal to marry girls of that age in Africa. It was encouraged in the first phase as an element of fraternization, but it was subsequently prohibited, I think in 1937 for a reason, yes racist, not to mix our race with the indigenous ones.”[xxvii]

The Fairy Tales

So why, despite all the documents, is the dark face of Italian colonialism not known enough even in Italy? According to the general view, the most important reason for this is that the anti-fascist governments established after the World War II did not deliberately focus on the issue sufficiently, as observed by journalist Giorgio Ghiglione:

“After the end of World War II, Italy’s new ruling class, largely composed of anti-fascists, created two intertwined myths: the myth of the “good Italian colonialist” and the myth of the “good Italian soldier.” Italian soldiers, so went the narrative, were poor and generous, reluctant to fight the war, and always willing to help the natives, as opposed to the true villains, the Germans. The point was that Italians, as a people, were good-natured, and that such good nature persisted even when they were misled by an evil regime. The aim was to create a sense of cohesion between the new anti-fascist government and the general population, by reassuring the latter they don’t share the blame of the dictatorship’s deeds. Even if they were staunch opponents of Mussolini’s regime, the new ruling class chose to forget the atrocities it committed in Africa, because admitting to them would have clashed with their narrative. After all, how could Italian troops, who were of course always eager to help the natives, even think of committing a war crime?”[xxviii]

On the other hand, immediately after the Great War, Ethiopia applied to the ONU for the punishment of Italian war criminals, especially Pietro Badaglio and Rodolfo Graziani, but could not get results, thus closing the way to international courts. The post-war balances were extremely fragile, and the victorious states left the trial decision to Rome, because they did not want to lose Italy by punishing it more. As a result “no real Italian war crimes trials ever emerged as they did at both Nuremberg and Tokyo.”[xxix]

Pietro Badoglio, in fact, retired after the war and completed his life in the city of Asti. Rodolfo Graziani, however, became the Minister of Defense in the Italian Social Republic (also known as the Repubblic of Salo’), established with the support of Nazi Germany after the capture of southern Italy by Anglo-Saxon troops during the World War II, and was sentenced to 19 years prison in post-war for collaborating with the Third Reich and not for his activity in Africa. Already 4 months later he was released, joined the Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement) and was elected honorary president of the Movement in 1953, he died in Rome.

Then again, it should not be forgotten that many fascist hierarchs and soldiers died during the Great War, that Badoglio or Graziani were not the only culprits, they were just two marked figures in a generation built on violence.

As has been underlined in many articles on the subject, Italian colonialism ended up largely forgotten, by the institutions and by public opinion, leaving a perfect void for those who want to fill it with fairy tales. Thus, over time, right-wing populist politicians have pushed aside the difficult issues and emphasized certain aspects of colonialism that might be viewed positively by someone. Even when they had to acknowledge some of the crimes of colonialism in the light of undeniable documents, they tried to divert attention by claiming that other Europeans had committed much more serious crimes. In short, it’s always the same old story: My colonist is better than your colonist.

Experiments in revisionism, such as those carried out by Deputy Minister Cirielli, tell more fantasies than facts. Fantasies create illusions and illusions turn into frustration. However, the facts will determine our future.

The good Italian

The definition of the “good Italian” is sure not a myth. But when historical circumstances change, when a wild and woolly order dominates the world, even the best Italian or the best human can be plunged into gruesome crimes. History, in fact, is there for this: Not to forget who we are.

To close my sentences exactly in this context, I leave the floor to the historian Andrea Ricciardi: “Hate propaganda can rapidly transform societies, people, especially when mobilized in conflict. The reality is that the Italian soldiers had been fascistized and barbarized, in order to conduct a military campaign as radical as possible against an enemy dehumanized by racial and confessional representations, which legitimized any action beyond the common principles of war law. […] Racism and contempt for the Ethiopian made him a non-man.”[xxx]

Notes

[i] M. Valeri, 2023, p.30

[ii] https://www.wallstreetitalia.com/piano-mattei-per-lafrica-cose-e-cosa-prevede/

[iii] https://www.open.online/2023/07/01/roma-viceministro-cirielli-colonialismo-italiano-africa-video/

[iv] http://www.rifondazione.it/primapagina/?p=53886

[v] http://www.qattara.it/balbia_files/Opere%20italiane%20in%20Africa.pdf

[vi] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2013/09/30/colonialismo-in-africa-litalia-non-puo-dimenticare-sua-storia/727890/

[vii] http://www.cronachediordinariorazzismo.org/cirielli-il-rimosso-storico-del-colonialismo-italiano-e-del-razzismo-strutturale/

[viii] https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/30/as-europe-reckons-with-racism-italy-still-wont-confront-its-colonial-past/

[ix] https://laricerca.loescher.it/massacri-italiani-in-etiopia-e-coscienza-storica/

[x] https://www.raicultura.it/storia/accadde-oggi/Oro-alla-Patria-df78dccd-98ce-403f-9e5f-295e360d5f02.html

[xi] http://www.psychiatryonline.it/node/4489

[xii] https://laricerca.loescher.it/massacri-italiani-in-etiopia-e-coscienza-storica/

[xiii] https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/hum/article/view/1404/1119

[xiv] https://lyricstranslate.com/en/faccetta-nera-pretty-black-face.html

[xv] https://www.novecento.org/didattica-in-classe/razzismo-coloniale-italiano-dal-madamato-alla-legge-contro-le-unioni miste-3634/1937/

[xvi] http://www.anpiroma.org/2013/07/rodolfo-graziani-soldato-o-criminale-di.html

[xvii] https://www.corriere.it/cultura/22_gennaio_21/libia-crimine-fascista-rimosso-orribili-campi-cui-morivano-civili-8065b00c-7ae5-11ec-bb07-072210d17db2.shtml

[xviii] https://www.istitutoeuroarabo.it/DM/revisionismo-e-indifferenza-la-vicenda-del-mausoleo-a-graziani-di-affile/

[xix] https://www.unive.it/pag/fileadmin/user_upload/dipartimenti/DSLCC/documenti/DEP/numeri/n10/10_Dep_010Volpato.pdf

[xx] https://www.articolo21.org/2023/07/leterno-mito-degli-italiani-brava-gente-e-il-falso-piano-mattei/

[xxi] https://www.fanpage.it/esteri/quando-gli-italiani-in-3-giorni-massacrarono-30mila-uomini-donne-e-bambini-innocenti-in-etiopia/

[xxii] Del Boca 1996, p. 88

[xxiii] Rochat, 2009, p. 210

[xxiv] https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/30/as-europe-reckons-with-racism-italy-still-wont-confront-its-colonial-past/

[xxv] https://www.corriere.it/extra-per-voi/2016/04/02/armi-chimiche-etiopia-l-ammissione-montanelli-54d37986-f8fc-11e5-b97f-6d5a0a6f6065.shtml

[xxvi] https://www.agi.it/archivio/storico/litalia_uso_i_gas_in_etiopia_lo_prova_il_diario_di_un_soldato-226618/news/2009-01-06/

[xxvii] https://www.rollingstone.it/politica/montanelli-razzista-secondo-lo-storico-del-boca-quel-matrimonio-e-un-atto-di-integrazione/521513/

[xxviii] https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/30/as-europe-reckons-with-racism-italy-still-wont-confront-its-colonial-past/

[xxix] https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/italian-war-criminal-rodolfo-graziani/

[xxx] https://laricerca.loescher.it/massacri-italiani-in-etiopia-e-coscienza-storica/

Leave a Reply