In 1798, the French, under the leadership of Napoléon Bonaparte, invaded the Ottoman province of Egypt. That same year, the British defeated the French navy at the Battle of Abukir. Nevertheless, the French retained a presence in Egypt until 1801, when they were forced out of the territory by joint British Ottoman forces. In 1799, Napoléon led an expedition into Syria-Palestine but was unsuccessful in establishing any kind of permanent foothold there. From Syria-Palestine, Napoléon evaded British forces and in 1799 returned to France as a hero; he would later go on to rule France and establish a continental empire in Europe. France and establish a continental empire in Europe Turkish conquest transformed Egypt into a province of the Ottoman Empire. The administration was in the hands of officials trained in Istanbul, known as pashas, who had to ensure that taxes were collected and delivered to Istanbul. The Mamluks remained powerful figures in the army and the administration of Egypt.[i]

Egypt became a pawn in the struggle for power between France and Britain when Napoleon wanted to gain control over Egypt in order to disrupt British commerce and eventually overthrow British rule in India. His fleet landed in 1798 in Alexandria, where he declared his intention to liberate Egypt. While Napoleon succeeded in occupying Cairo, the British navy, under Admiral Horatio Nelson, thrashed his fleet at the Mediterranean port of Abukir Bay.

Suleyman Halebi, a 23-year-old Ottoman mujahideen who could not digest the invasion of Egypt and assassinated the French commander, General Jean-Baptiste Kléber, in his headquarters in 1798, but was captured and martyred by French soldiers in 1800. The sign of Aleppo’s severed head was sent to Paris for orgy and is still exhibited in the Human Museum in the category of “Murderers”. It is the duty of the dignitaries of the Republic of Turkey to save the honor of this heroic Ottoman citizen, who gave his lesson to the French General who polluted the soil of his homeland, by taking the skull of this heroic Ottoman citizen from the Paris Museum and burying him in the lands he belongs to. This article is dedicated to an Ottoman hero Suleiman of Aleppo who fought French colonialism in Egypt.[ii]

The Response of Suleiman of Aleppo to the French Occupying in Egypt

On June 14, 1800, Suleiman of Aleppo went to Kléber’s house, disguised as a beggar who wanted to meet with General Kléber. As he approached him, Kléber held out his hand for Suleiman to kiss his hand. Instead, Aleppo violently pulled the general towards him and stabbed him four times with a dagger. He was 23 years old man when he killed the commander of the French expedition on Egyptian soil. Although Kléber’s chief engineer tried to defend him, he could not stop Suleiman, who was determined to kill the French general who had murdered thousands of innocent Muslims.

When Suleiman was searched by French soldiers, he was found in a park in Cairo and tortured. His right arm was burned to the bone during the torture, and he denied any involvement with Sheikh Abdullah al-Sharqawi and the popular resistance movements. He was tried of torture for days and sentenced to death. French sources write that he died while reciting verses from the Qur’an for four hours during torture.[iii]

Who is French General Jean-Baptiste Kléber?

Jean-Baptiste Kléber was a Christian general of Egyptian origin during the French Revolutionary Wars. He entered Habsburg service seven years after serving in the French Royal Army. Eventually, he volunteered for the French Revolutionary Army in 1792 and rose quickly. Kléber served in the Rhineland during the First Coalition War and suppressed the Vendée Revolt. Although he retired during the peaceful interlude after the Treaty of Campo Formio, he returned to military service to accompany Napoleon in the Egyptian Campaign of 1798-99. When Napoleon left Egypt to return to Paris, he appointed Kléber as commander of the French forces.

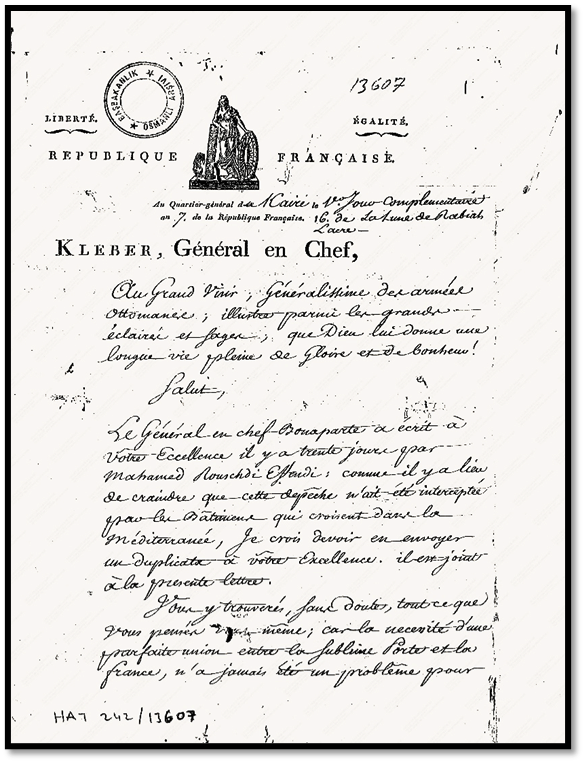

He accepted the administration of a division in the Egyptian campaign under Bonaparte but suffered a head injury in the first engagement at Alexandria. This led to his participation in the Pyramids expedition and his appointment as governor of Alexandria. He commanded the vanguard in the 1799 Syrian campaign, captured Al-Arish, Gaza and Jaffa, and won the great victory at Mount Tabor on April 16, 1799. When Napoleon returned to France in late 1799, he left Kléber as commander of the French forces. In this capacity, he signed the Al-Arish Convention on January 24, 1800 for the honourable evacuation of the French army, negotiating with Admiral Sidney Smith, in hopes of returning his army to France or consolidating his occupation policies. When Admiral Lord Keith refused to agree to the terms, Kléber attacked the Ottoman army at the Battle of Heliopolis. Despite having only 10,000 men against 30,000 Turks, Kléber’s forces defeated the Ottoman army on March 20, 1800. He then recaptured Cairo, where a revolt started against the French rule.[iv]

Kléber, a mason, is known to have been instrumental in bringing freemasonry to Egypt. While negotiating with Sidney Smith in January 1800, Kléber opened a Masonic temple in Cairo, thereby establishing the lodge of Isis (La Loge Isis), which served as its first lord. The motto of the lodge was the slogan of the French revolution, which was Liberté, égalité, fraternité.

Shortly after these victories, Kléber was stabbed by Suleiman, a student living in Egypt, while walking in the garden of the Alfi bika palace. According to French sources, Suleiman appeared to be begging Kléber, but quickly grabbed his hand and stabbed him in the heart, stomach, left arm and right cheek. Shortly after he was captured, he still had the dagger he used to kill Kléber, and after a series of tortures he was executed. The assassination occurred on June 14, 1800, in Cairo. After Suleiman was captured, his right arm was burned and impaled in a public square in Cairo, where he was left to die. The skull of Suleiman was sent to France and used to teach French medical students the features of the skull that indicate “crime” and “fanaticism,” as claimed by French phrenologists. According to the interrogation records of the French colonial police, al-Halebi, who was identified by the engineer, was arrested, and sent to prison along with the four people who were aware of the assassination.

After being tortured, he confessed to the assassination and said that he was commissioned by the Ottoman Janissary Aghas to kill Kleber, who had suffered great losses to the Ottoman armies. The colonial administration had decided that he should be impaled, and his friends beheaded four other scientists.

Less than a year after Kleber’s assassination, the French forces in Egypt were forced to withdraw. The French doctor Dominique Jean Larry, who witnessed the execution, recorded in her book written in 1803 that Suleiman did not give up his proud stance until he died.[v]

The honour of Suleiman of Aleppo waits to be rescued

The French occupation forces had transported the skull and dagger of Suleiman to France. This dagger is still on display in a museum in Carcassonne as a witness to his bravery to this day. The skull is also on display at the Museum of Man in Paris under the name “the skull of a criminal”, which is evidence of the brutality of the occupation. Egyptian writer Alfred Farag brought up Aleppo again in a play in 1965, and his name was given to a neighbourhood in Aleppo.

It is hard not to wonder when the skull of the valiant son of the Ottomans, mujahid Suleyman, will be exhibited in a museum in France. Similarly, the body of Sarah Bartmaan from Cape Town, who was put in the human museum in France at the same time, was brought from Paris years later in 2002 with the diplomatic initiatives of Nelson Mandela and buried in her homeland. Mandela had rescued from Paris not only Barthmaan’s body, but South Africa’s honour.[vi]

Now its Suleiman’s turn. This duty belongs to the Republic of Türkiye as the successor of the Ottomans, to protect the honour of Suleiman of Aleppo. Martyr Suleiman, a student of science who defended the Islamic city of Egypt at the cost of his death, is waiting to return to his country to be buried in his homeland. With this diplomatic move, not only will an answer be given to France, but also the cherished spirit of Ottoman mujahid Suleiman Halebi.[vii]

Notes

[i] Maze-H Maze-H. 2018. Les Generaux De La Republique. Kleber Hoche Marceau. Hachette Livre – Bnf.

[ii] الفريد and فرج، الفرد. 1965. سليمان الحلبي : مسرحية. Cairo: دار الهلال،. Sulaymān al-Ḥalabī : masraḥīyah

[iii] Larrey D. J. 1803. Relation Historique Et Chirurgicale De L’expédition De L’armée D’orient En Egypte Et En Syrie. Paris: Demonville.

[iv] Hasan İzzet and Erkutun M. İlkin. 2009. Ziyânâme : Sadrazam Yusuf Paşa’nın Napolyon’a Karşı Mısır Seferi 1798-1802. İstanbul: Kitabevi.

[v] Orhon Nafiz Taşdelen Nuri and Turkey. 1987. 1798-1802 Osmanlı Fransız Harbi (Napolyon’un Mısır Seferi). Ankara: T.C. Genelkurmay Başkanlığı.

[vi] Gençoğlu Halim. 2018. Güney Afrika’da Zaman Ve Mekân : Ümit Burnu’nun Umudu Osmanlılar 1. Baskı ed. Osmanbey İstanbul: Libra Kitapçılık ve Yayıncılık.

[vii] Richardson Robert G. 1974. Larrey: Surgeon to Napoleon’s Imperial Guard. London: Murray.

Leave a Reply