By Michael Roberts *

Published on October 30 before the elections, Roberts’ article provides deep insight into Brazil’s economic situation and challenges. These have not changed with the election results, quite the contrary, Roberts’ article describes the landscape that President-elect Lula faces. Therefore, we consider the article of great value, UWI.

The latest polls put Workers Party leader Lula de Silva ahead in the two-horse race with incumbent right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro in today’s final round of the presidential election in Brazil. If Lula wins, it will be a dramatic comeback for the former president after having been jailed for alleged corruption under the previous right-wing Temer regime; and then finally released and allowed to run again. A Lula victory will mean that the Workers Party has regained the presidency after losing it when last WP leader Dilma Rousseff was impeached by a right-wing Congress in a ‘soft coup’ in 2016.

The victory of ‘Tropical Trump’ Bolsonaro in 2018 was achieved mainly because of the disillusionment by sections of the working class with the Workers Party and the successful media campaign claiming that the WP was corrupt. After the collapse of commodity prices in resources and agriculture in 2014, the economy went into recession. The blame for this and corruption was laid at the door of the Workers Party. But the experience of the COVID slump under Bolsonaro, when over 750,000 Brazilians died, has been so searing that, apart from his base among evangelical Christians and petty-bourgeois business people, it seems enough Brazilians will have turned away from him and returned to Lula, despite his past record, in hopes for better.

Whoever wins, what now for Brazil’s economy? The economy has been slowly recovering from the COVID slump, based on rising commodity prices over the last year. But Brazil’s long-term economic record, especially since the Great Recession, is one of slowing growth in GDP and productivity, rising private and public debt and above all, of extreme inequality in wealth and incomes.

The economic roller coaster ride of the last decade is reflected by Brazil’s ranking among the world’s largest economies. Between 2010 and 2014, Brazil ranked seventh. In 2020, it slipped to 12th place. And in 2021 it dropped to 13th, according to Austin Rating. The trend growth rate has been falling.

Brazil: real GDP growth rate (annual %)

And Brazil has nearly the highest measure of income inequality in the world.

Former President Lula put it more dramatically: “In Brazil, 33 million people don’t have enough to eat,” he wrote on Twitter. “We managed in the past to get Brazil off of the world map of hunger. But hunger is back.”

Can Lula turn that round? Well, if the past record of Lula is anything go by, then the prospects are mixed. There is an excellent analysis of the economic performance of previous WP administrations by Brazilian Marxist economist Adalmir Marquetti and colleagues. This is how they sum up the impact of previous PT administrations. “The PT governments combined elements of developmentalism and neoliberalism in a contradictory construction, organizing a large political coalition of workers and capitalists that allowed expanding the real wage and reducing poverty and inequality while maintaining the gains of productive and financing capitals. The decline of profitability after the 2008 crisis broke the class coalition constructed during Lula’s administration. The Dilma Rousseff government adopted a series of fiscal stimuli for private capital accumulation with meager economic growth. After her reelection, the government implemented an austerity program that resulted in negative growth rates. With the deepening economic crisis and without political support, Rousseff was removed from power.”

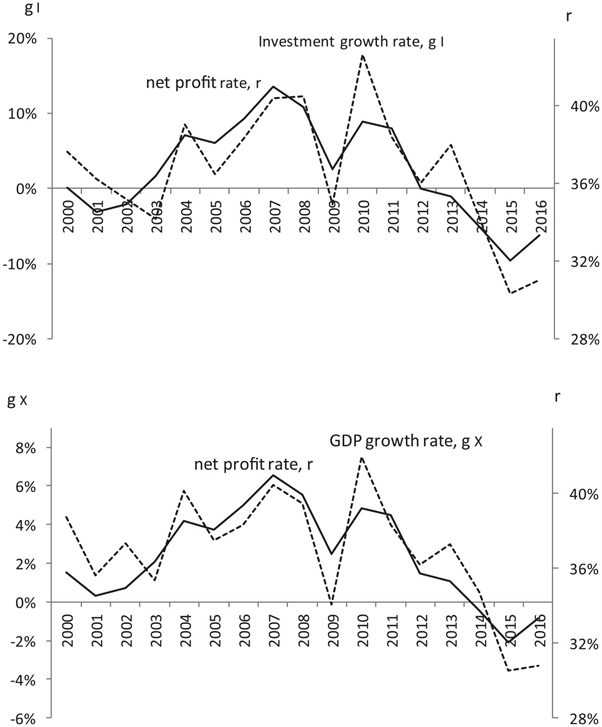

Marquetti et al argue that the decline of profitability after the 2008 crisis played a key role in breaking the political coalition organized under Lula’s leadership, opening the possibilities for the soft coup of 2016. That’s because investment and GDP growth rates were strongly associated with the profit rate in Brazil between 2000 and 2016.

Between 2003 and 2007, the profit rate increased despite the decline of the profit share because of an increase in capacity utilization and in the potential productivity of capital. Between 2007 and 2015, the profit rate declined because of an increase in the wage share and a drop in the potential productivity of capital. In 2010, the last year of Lula’s government, the profit rate was still higher than in the early 2000s. However, the long-term path of the profit rate started to decline after 2010 at the end of the commodity price boom globally. “The simultaneous decline in the profit rate and financial profitability was the beginning of the end of the class coalition constructed by Lula’s government.”

The Rousseff government turned to neoliberal policies in attempting to overcome the decline of growth associated with falling profit rates in Brazilian capital. Rousseff sought a rapprochement with the sectors of the bourgeoisie, contrary to her promise during the election campaign. The first fiscal measures, announced in January 2015, restricted workers’ access to unemployment insurance and changed the rules for some social security benefits. There was a reduction of fiscal spending; federal government investment declined 32 percent in 2015.

The government capitulated to the view of Brazilian big business, enshrined in its newsletter of July 2016 (Institute of Industrial Development Research, a think tank linked to big Brazilian industry, “No Profits, No Investments” (IEDI, 2016). The adopted neoliberal economic policy increased unemployment and reduced the real wage. But this capitulation did not save Rousseff from her impeachment by Congress and the institution of a right-wing government.

This is the danger ahead for a new Lula administration. It will not have a majority in Congress and will face a vicious media campaign. And it seems that Bolsonaro has cemented a coalition of the right based on religious and crazed petty bourgeois layers, and an antagonistic upper middle class particularly in the big cities of the south; with Lula relying on a somewhat disillusioned working class.

The economic recovery of the last year has also bolstered support for the Bolsonaro coalition as official unemployment has fallen to its lowest level in nearly seven years (although it is still above levels before the Great Recession of 2008-9).

Official unemployment rate (%)

Inflation is also falling but still well above pre-pandemic levels.

CPI inflation yoy %

The Brazilian economy expanded 3.2% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2022, picking up from the 1.7% advance in the previous three-month period and surpassing market forecasts of a 2.8% rise. But this modest recovery is unlikely to last into 2023 as the world economy heads into a new recession that Brazil cannot escape.

It is often reported that Brazil’s public sector runs the largest debt to GDP among all emerging economies. But more important, private sector debt (as % of GDP) is now at a record high.

Private sector debt to GDP (%)

With global interest rates rising fast, this is bound to weigh heavily on Brazilian companies and their ability to expand investment profitably.

The IMF forecasts just 1% real GDP growth for Brazil next year. At the same time, more than half of Brazil’s population remain below a monthly income per head of R$560. To cut this level of poverty to under 25% would require productivity four times as fast as the current rate. And there is no prospect of that under capitalism in Brazil.

That’s because the profitability of Brazilian capital is low and continues to stay low. The profitability of Brazil’s dominant capitalist sector had been in secular decline, imposing continual downward pressure on investment and growth – to quote the Brazilian industry association above: ‘no profits, no investment’.

Source: Penn World Tables, author

As Marquetti et al have shown, the profitability of Brazil’s capitalist sector is key to investment and production growth. Brazilian capitalism will be stuck in a low growth, low investment future with continuing political and economic paralysis. And that is even without a new global recession coming over the horizon.

* Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. At the same time, he was a political activist in the labour movement for decades. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.

This article was previously published on his website and can be read here.

Leave a Reply