In the last decade, the Mediterranean has become a global epicenter of geopolitical and geo-economic interests. It has taken an increased importance because of the profound transformations that have taken place and that continue to manifest themselves in ever fluid and changing forms. The regional conflicts in Libya and Syria, the never-ending tensions between Turkey, Greece and Cyprus (Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus), the claims of the coastal states on offshore natural gas resources, the disputed maritime borders in the Levant Sea, as well as the competitive policies of intra- and extra-regional powers are just some of the main drivers of instability in the central and eastern Mediterranean.

In addition to these crisis factors, there are the socio-economic and lasting effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and the consequent collapse of energy prices on a global scale. In fact, the Mediterranean operational context is full of conflicting elements, in which various challenges and opportunities are clearly discernible. It is no coincidence that in a constantly evolving ‘Mare Nostrum’ it is a strong activism of many important actors. Egypt, Turkey, Israel, France, Greece, Cyprus, Russia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, all of them are keen to satisfy their respective economic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean and their own important geopolitical ambitions to reinforce, and possibly expand, regional and international status.

Geo-economic relevance

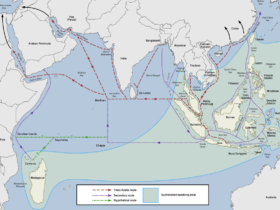

The enlarged Mediterranean, i.e. the region between the Gibraltar-Gulf of Aden line, the Middle East and the northern shore of the Mediterranean. Along with the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean has become a mid-ocean, an artery linking the Indo-Pacific and the Atlantic, through which one third of world maritime trade passes. Therefore, the Mediterranean and the MENA area have acquired a new and more important centrality in the international economic and geopolitical scenario. The foreign trade (import-export) of the main countries of the world (from China to the USA) and of Europe (Germany, Italy, France) towards the countries on the southern shore of the Mediterranean is constantly growing.

In the last 20 years, the economies of the MENA countries (Middle East and North Africa) have had an average GDP growth of +4.4% per year, higher than the average growth recorded in the European Union.

Multipolar Mediterranean

In this scenario we see the slow but inexorable loss of hegemony and centrality of the United States and its imperialist vassals, particularly after the new dynamics that have emerged in the region following the season of the so-called ‘Arab springs’, and the contextual entry of a new actor on the Mediterranean scene: China.

The Asian giant has increased its foreign trade with this area by 841% in recent years; much of this trade has been by sea and has passed through the Suez Canal, which, thanks to the enlargement in 2015, is now the main hub of world maritime traffic. Early post-enlargement figures indicate sustained growth, and today Suez has a total traffic volume that is almost four times that of the Panama Canal. Suez is also central to China’s strategies and the relaunch of the ancient Silk Road (Belt and Road Initiative).

Chinese investments in the Canal and Egypt, with the presence in the ports of Piraeus, Spain and Italy, outline a strategy of strong presence in the Mediterranean. On the other hand, it is enough to consider that the European GDP of more than 15,500 billion euros and that of the MENA countries of more than 3,500 billion (a value that together far exceeds the US GDP) are the basis for an overall exchange of the Euro-Mediterranean area with China that reaches 751 billion dollars per year.

In the light of the new centrality of the Mediterranean, Chinese investments in the Maritime Silk Road are considerable. Today, the acquisitions in the enlarged Mediterranean have exceeded the value of 5 billion dollars and the main investor is China. Overall, Beijing holds shares in all the ports involved in the Maritime Silk Road.

These enormous changes and numbers show how the world’s center of gravity has now shifted eastwards, towards Eurasia.

Not only does China mark the multi-polarity of the Mediterranean, there is also the return of Russia to the Mediterranean. Moscow wants to return to the Mare Nostrum to strengthen its position and promote its interests.

Russia considers its presence in the Mediterranean crucial to ensuring a leading role in the global chessboard, in that mid-ocean, in particular its eastern part, the main way to reach the Suez Canal, the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. All of these are privileged corridors for international trade routes and for the movements of the U.S. and European military fleets.

The return of Russia to the Mediterranean comes after the security of the country on the domestic front. The eradication of the scourge of terrorism (especially of Chechen origin), the economic revival, athe formation of a middle class are just three objectives that Putin has achieved during his time in power, pursuing these goals with a determination that has distinguished his political action.

For Moscow, in fact, as pointed out by authoritative analysts (Centre for International Studies – CeSI, 2020) “the Mediterranean represents a natural border for NATO: sailing freely in its waters means expanding the opportunities for deterrence against the United States and its allies, an advantage that was particularly important during the Cold War period, but which is still very relevant today”.

Parag Khanna, an Indian political strategist, wrote in an essay entitled The Asian Century?: “since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western strategists have repeatedly said that Russia would have no choice but to accept NATO expansion and a subordinate role in an alliance with the US and Europe.

Evidently, this is not what happened, as the strategists of the Western countries predicted and desired. Russia has returned to the scene as a global power.”

On top of profoundly redefining the balance of power in the area, this has had, and will have, repercussions on the world order. According to some commentators, the presence of the Russian navy in Syria and the Mediterranean in general is not only a facade, it is tangible, and has sanctioned the end of the ideals and military hegemony of the United States. In the Mediterranean, as in other parts of the world such as Latin America, growing ties with China and Russia show how an increasingly multipolar system offers the countries of the global South new potential allies that can serve as bulwarks against suffocating US hegemony, finally offering valid alternatives.

Leave a Reply