During the COVID-19 crisis, many countries in the world launched stimulus measures to stop the deterioration of their productive and financial sectors. Rich nations, based on a growing indebtedness, have carried out unprecedented fiscal interventions to prevent economic collapse. How will that be paid for once the global recovery begins? The Global South has not had the same opportunity.

Debt, domestic macroeconomic mismanagement, currency crises, commodity price shocks, fear of credit rating downgrades and pressure from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are the main drivers that have led countries in the South into distress and prevented them from adopting the kind of fiscal stimulus measures countries in the North are now adopting or have already adopted.

Public debts have grown around the world, even in industrialized nations. Japan is the most indebted (almost 257% of its Gross Domestic Product, GDP), followed by Italy (154%) and the United States (133%), according to the IMF. This year, debt levels reached a world record of $296 trillion by September 2021, which implies exceeding the pre-pandemic debt level by $36 trillion. Eurostat indicates that the public debt of the entire European Union is 12 trillion euros and 11.1 trillion for the Eurozone. In total, that’s equivalent to 353% of the global economy’s GDP, according to the Institute of International Finance. About half of the debt corresponds to China and the US, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Households, nation-states at different scales, non-financial corporations and the financial sector are all indebted. How will that trend continue to develop? Could it lead to a major debt crisis?

Latin America and the Caribbean

The external debt in the region has been, forcefully since the 80s, a system of submission and dependency. Over the past 50 years, Latin American and the Caribbean countries (LAC) have experienced at least 50 sovereign debt crises and sovereign debt restructurings. The IMF has played a central role in that story.

Member countries approach the IMF when they have balance of payments problems. IMF impose restructurings and austerity programs which usually result in impediments to growth and development, also forbidding social spending programs. The IMF considers it its task to act and decide on the productive base of the economies of peripheral countries, restructure internal sectors, conditioning future scenarios, within the framework of immediately applicable adjustment policies. The World Bank (WB) and the IMF are twin institutions controlled by the US. Decisions are made based on the quota and voting shares of the member countries, in proportion to the financing that each one contributes. The US has a vote share that signifies a de facto veto right. To endorse important decisions it is necessary to have 85% of the votes of all members, and the US has 16.50%, so any action taken must have the approval of Washington. Along with them dominate Japan, China, Germany, France and Great Britain (between 4% and 6% of the vote respectively).

The volume of external debt of LAC´s countries doubled in 1990, and from then until 2019, it grew 10 times. The COVID-19 crisis confirmed and accelerated this process. For instance, by the end of 2020, more than 60% of the IMF emergency financing went to LAC. Between 2019 and 2020, there was an increase in debt levels in the region from 68.9% to 79.3% of GDP, which makes it “the most indebted region in the developing world and the region with the highest external debt service relative to exports of goods and services (57%)” as Alicia Bárcena herself, Cepal’s executive secretary said.

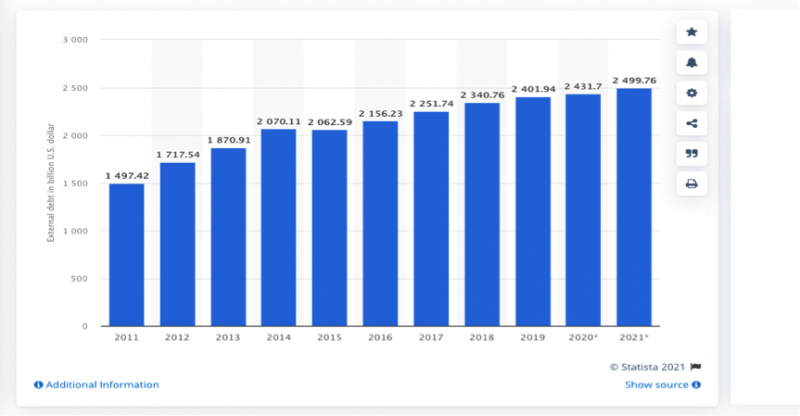

Graph 1: Latin America and the Caribbean: External debt from 2011 to 2021 (in billion U.S. dollar)

There is nothing new under the sun in the 21st century. In 1985, Fidel Castro participated in the External Debt meeting of Latin America and the Caribbean and said the debt of poor countries “is not payable even in dreams. We say: it is unpayable.” He also said that so-called Third World countries have transferred enormous amounts of capital to rich states in terms of debt interest payments, while they were subjected to fluctuations in the prices of the products they export (mainly commodities), and the recurring catastrophe that remains after the application of the structural reforms required by the credit institutions.

The debt system stipulates that debt exists so that it can never be repaid. Countries in economic distress, with little growth and small generation of international currency, dedicate the bulk of their resources to debt service, to the detriment of investment in other sectors of society, especially what has to do with the well-being of the huge masses of the poor (e.g., Argentina is close to 50% poverty among its 44 million inhabitants). According to a new report from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF, April 2021) in 2019, 25 countries in all regions allocated higher budget allocations to debt service than to education, health and social protection combined.

David Malpas, President of the World Bank, at the roundtable during Annual Meetings 2021 (October) declared that the annual International Debt Statistics report for 2022 identifies a 12% increase in the debt owed by low-income countries, which reached $860 billion, reaching in some cases, 20% or more. As of mid-2021, over half of the 75 poorest countries were in external debt distress or at high risk of it, he said. For most countries the rise in external indebtedness was not matched by the growth of Gross National Income (GNI) and exports, Malpas said.

Graph 2: External debt as percentage of Gross Domestic Product in Latin America in 2020, by country

Argentina and Ecuador

The South American country is in the middle of a $320 billion negotiation owed to bondholders, credit organizations and public sector agencies. The excluding negotiating agent is the IMF.

Argentina’s debt problem dates back decades. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, the country’s debt increased 40 times. The neoliberal government of Carlos Menem, an ally of Washington in the 90´s, tripled the debt. The next government, a neoliberal centrist force. led the country to default, and a social crisis broke out. The last two indebted the country while channeling the flow of dollars abroad.

Since 2003, amid a strong inflow of dollars through a reactivated and growing economy, the relationship with creditors stabilized, and the Kirchner governments moved freely and autonomously within the framework of the recomposition of society. However, during Kirchnerism (2003-2015) Argentina’s nominal debt continued to increase going from $180 billions to more than $240 billions. However, its real weight on the economy was drastically reduced.

This was reversed with the arrival of Mauricio Macri. As soon as he took office, he decided to pay what the creditors asked, reopening Argentina’s path to credit, after being closed due to the blockade of the holdouts. Argentina’s debt soared again. By the end of Macri’s term (December 2019), the debt exceeded $320 billion and Argentina became the recipient of the largest credit granted by the IMF in its entire history. The current Minister of Economy revealed that four out of every five dollars that the IMF loaned to the Macri government were in turn used to pay off public debt in foreign currency or capital flight. The IMF thus violated its own regulations, which prohibit it from lending money to finance capital outflows. Without borrowing since 2019, Argentina is among the 10 most indebted countries in the world.

The Andean country is another of the nations that has the highest external debts as a percentage of GDP. In March 2020, the Ecuadorian Congress asked the government to suspend debt payments and allocate those resources to the response to the pandemic. The government of the banker Lasso last April requested four months of deferral of $ 800 million in interest payments and expressed its intention to restructure the debt. Despite achieving a reduction in short-term debt service, the IMF imposed cuts in public spending by $4 billion, including a reduction in working hours and the salaries of government employees.

Ecuador has an external debt of 52 billion dollars. The IMF had stipulated that the country would need at the end of 2021 more than 7 billion in new financing. Last September it was announced that the country would receive 6 billion, coming from different organizations. The condition was that the country agree to cut its budget deficit by $ 2,8 billion, a figure that is large for the Ecuadorian economy, which has a GDP somewhat less than 100 billion. This unleashed protests by unions, political organizations, and students at the end of October.

Conundrum and decision time

There has been a sharp increase in indebtedness and fiscal deficit in the region. Economic expectations are obscure, long-standing low growth and inequality challenges have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Inequality and dependence between the center and the periphery are deepening. How will Latin American countries meet these challenges?

In a press release (June 2021) the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in its latest World Investment Report, highlights that foreign direct investment flows to Latin America plunged by 45% in 2020, to $88 billion dollars. The dependence on the export of commodities will remain and reign together with the financial system. On the other hand, the social and health situation of the popular classes most affected by the crisis resulting from the pandemic is deteriorating at a terrifying rate.

Our region recently experienced insurrections and popular revolts in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Haiti, and Bolivia. Right-wing conservatives and neoliberals took over governments and quickly lost them, after applying recipes inspired by the Washington Consensus. Popular, progressive, moderate governments took over in a context of crisis that accelerated with the pandemic. All are subjected to the debt system and have decided not to break with it nor confront it. Financial power is dominant. In Argentina, the Fernández government denounces the debt acquired by Macri as fraudulent but has still agreed to pay it. Ecuador is governed by an agent of the financial system. Both countries urgently need dollars and their economies either don’t produce them, help or watch as they fly away, or linger outside the registered system.

In 2020, food insecurity reached 40% of the population of Our America (in 2019 it was 33.8%); that is, 249 million people did not have regular and sufficient access to food (CEPAL). The International Labour Organization (ILO) reported the global loss of more than 140 million jobs during the same year. Meanwhile, wealth increased by 7.4%, and the inequality in its distribution is significantly higher than that registered in any year of this century (Global Wealth Report, by the Credit Suisse Research Institute, June 2021). The US and Canada recorded the highest increase in wealth, 12.4%, Europe 9.2%, China, 4.4%. In LAC conversely, wealth decreased 11.4%.

Previously, LAC countries have joined efforts to promote unity among their peoples. There are mechanisms of integration and cooperation of proven track record and effectiveness, active and combative, that still can lead Our America on a path of development in equality. The Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America – Peoples’ Trade Treaty (ALBA -TCP), are the well-known examples, but which have recently become sclerotic, if not neutralized by the conservative and liberal advances in the region.

Precisely, they are still an object of imperial interference and the devastating maneuvers of the local reactionary liberal or conservative elites, who are very clear that any such process must be stopped. Elites and imperialism altogether had confronted our American masses throughout the 20th and 21st century. They, who formed as ruling-ruling classes in diverse oligarchy orders during the 19th century, fighting the exploited and rebellious people, envisage this latent movement clearly and remember well the recent history of the continental articulation headed by Chávez and Fidel.

The debt burden, the insidious power of the WB and the IMF, the corporate trade regime, the dominance of the global intellectual property monopoly, the entire global economic architecture, must be transformed. Meantime, countries of the region must achieve definitive independence and autonomy, which includes the access to financial resources, as a viable way over time to sustain their economy to meet the growing and unresolved needs of their peoples. From a political point of view, it implies building a new force with solid international backrest, to stop or attenuate the imperialist interference and definitively defeat neoliberalism.

The only way to go on that path is, in addition to resolving internal contradictions, to act as a bloc, build regional articulation and joint response, which requires strengthening ties of brotherhood and solidarity, coordination, respect and collaboration between nations.

Leave a Reply