This is Algeria

or desert

From the ancestors that camels carried for thousands of years,

Love

Wisdom

My being is tormented

Oh dates, you have no taste,

Do you hear how the trampled sand cries out?

Get up mom

And woman walk

And son run

To the necessary salvation of meaning…

Fazıl Hüsnü Dağlarca – 1961

The occupation and colonization of Algeria had a special place in French history and politics, from the onset to independence, and it continues to be so. Understanding the mentality of the colonization and the interaction between peoples is as important as covering the series of events. Colonization of a territory brings with itself power struggles, changes in social and political structures, and turmoil in all areas of social life; and all these were present in French Algeria. This article focuses on these more general aspects of the colonization of Algeria from 1830 to 1960, bearing the relation between the mentality and the events in mind, and dealing with the issue under the topics of occupation, colonization, and resistance in an international context.i

The French first colonized Algeria in 1830, and remained within Algeria until 1962. The colonization was supposedly initiated by an Ottoman ruler slapping a French diplomat, but was more importantly a result of the failure of the French to pay their debts to Ottoman Algeria.ii

What did the French really do in Algeria?

With the decay of the Ottoman Empire, the French invaded and seized Algiers in 1830. This began the colonization of French North Africa, which expanded to include Tunisia in 1881 and Morocco in 1912. The occupation of Algeria was initiated in the last days of the Bourbon Restoration by Charles X, as an attempt to increase his popularity amongst the French people, particularly in Paris, where many veterans of the Napoleonic Wars lived. His intention was to bolster patriotic sentiment and distract attention from ineptly handled domestic policies by skirmishing against the dey.iii Even before the decision was made to annex Algeria, major changes had taken place. In a bargain-hunting frenzy to take over or buy at low prices all manner of property homes, shops, farms and factories, Europeans poured into Algiers after it fell.iv

French authorities took possession of the Ottoman lands, from which Ottoman officials had derived income to protect Algerian cities. Over time, as pressure increased to obtain more land for settlement by Europeans, the state seized more categories of land, particularly that used by tribes, religious foundations, and villages. Called either colons, Algerians or later, especially following the 1962 independence of Algeria, black feetv the European settlers were largely of peasant farmer or working-class origin from the poor southern areas of Italy, Spain, and France. Others were criminal and political deportees from France, transported under sentence in large numbers to Algeria. In the 1840s and 1850s, to encourage settlement in rural areas, official policy was to offer grants of land for a fee and a promise that improvements would be made. A distinction soon developed between the great settlersvi at one end of the scale, often self-made men who had accumulated large estates or built successful businesses, and smallholders and workers at the other end, whose lot was often not much better than that of their Muslim counterparts. According to historian John Ruedy, although by 1848 only 15,000 of the 109,000 European settlers were in rural areas, “systematically expropriating both pastoralists and farmers, rural colonization” was the most important single factor in the de-structuring of traditional society.vii Indeed, European migration, encouraged during the Second Republic, stimulated the civilian administration to open new land for settlement against the advice of the army. With the advent of the Second Empire in 1852, Napoleon III returned Algeria to military control. In 1858, a separate Ministry of Algerian Affairs was created to supervise administration of the country through a military governor general assisted by a civil minister.

Napoleon III visited Algeria twice in the early 1860s. He was profoundly impressed with the nobility and virtue of the tribal chieftains, who appealed to the emperor’s romantic nature, and was shocked by the self-serving attitude of the colon leaders. He decided to halt the expansion of European settlement beyond the coastal zone and to restrict contact between Muslims and the colons, whom he considered to have a corrupting influence on the indigenous population. He envisioned a grand design for preserving most of Algeria for the Muslims by founding an Arab kingdom with himself as the king of the Arabs. He instituted the so-called politics of the grand chefs to deal with the Muslims directly through their traditional leaders. To further his plans for the Arab Kingdom,viii Napoleon III issued two decrees affecting tribal structure, land tenure, and the legal status of Muslims in French Algeria. The first, promulgated in 1863, was intended to renounce the state’s claims to tribal lands and eventually provide private plots to individuals in the tribes, thus dismantling “feudal” structures and protecting the lands from the colons. Tribal areas were to be identified, delimited into douars administrative units and given over to councils. Arable land was to be divided among members of the douar over a period of one to three generations, after which it could be bought and sold by the individual owners. Unfortunately for the tribes, however, the plans of Napoleon III quickly unravelled. French officials sympathetic to the colons took much of the tribal land they surveyed into the public domain. In addition, some tribal leaders immediately sold communal lands for quick gains. The process of converting arable land to individual ownership was accelerated to only a few years when laws were enacted in the 1870s stipulating that no sale of land by an individual Muslim could be invalidated by the claim that it was collectively owned. The cudah and other tribal officials, appointed by the French on the basis of their loyalty to France rather than the allegiance owed them by the tribe, lost their credibility as they were drawn into the European orbit, becoming known derisively as béni-oui-oui.ix The second decree, issued in 1865, was designed to recognize the differences in cultural background of the French and the Muslims. As French nationals, Muslims could serve on equal terms in the French armed forces and civil service and could migrate to France proper. They were also granted the protection of French law while retaining the right to adhere to Islamic law in litigation concerning their personal status. But if Muslims wished to become full citizens, they had to accept the full jurisdiction of the French legal code, including laws affecting marriage and inheritance, and reject the authority of the religious courts.x In effect, this meant that a Muslim had to renounce some of the mores of his religion in order to become a French citizen. This condition was bitterly resented by Muslims, for whom the only road to political equality was perceived to be apostasy. Over the next century, fewer than 3,000 Muslims chose to cross the barrier and become French citizens. Thus, assimilation policy in Algeria partially worked after 300 hundred years Ottoman Rule.xi

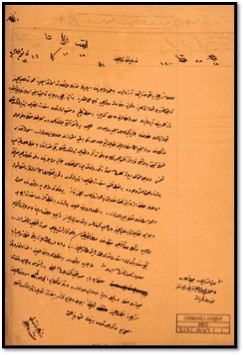

Ottoman Rule in Algeria

Algeria was an Ottoman territory centred on Algiers, in modern Algeria from the early sixteen century to nineteenth century. In 1516, the Spaniards later led numerous unsuccessful expeditions to take Algiers in the Algiers expedition and another failed expedition in 1541. Around the same time, the Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç Reis and Hayreddin were operating successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids.xii In 1516, Oruç moved his base of operations to Algiers and asked for the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1517 but was killed in 1518 during his invasion of the Kingdom of Tlemcen. Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers. The country was initially governed by governors appointed by the Ottoman Sultan rulers appointed by the Odjak of Algiers and then Deys elected by the Divan of Algiers.xiii

While the province continued to recognize the Turkish Sultan as suzerain, political control remained in the hands of the Janissaries until the French conquest of Algeria in 1830. The fiction of direct Ottoman control was eventually abandoned when in 1710 the Sultan issued a decree that vested executive authority in a Dey elected by the Turkish soldiers stationed in Algeria. Despite the dominant role played by the Janissaries in Algeria, their economic dependence on the activities of the Ta’ifa ul-Ru’asa (corporation of corsair captains) forced them to share some political power with that body. The Ta’ifa ul-Ru’asa was ultimately responsible for the institution of the Deylik in 1671 when the army failed to keep order in the Pasalik. The country did not suffer greatly from the political changes that occurred throughout this period, since the administration of the state remained in the hands of a bureaucracy which competently carried out the duties of government and maintained law and order. Indeed, though over half of the thirty elected Deys were assassinated, Algeria still functioned as a solvent, effective and generally well-ordered state. Eventually, however, the Pasalik’s preoccupation with piracy and the designs of an Empire-conscious French minister l led Ottoman Algeria to the fatal conflict with France and to ultimate extinction.xiv

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers had greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and of the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on French credit. In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria’s ruler, demanded that the French pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 by purchasing supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic Campaign in Egypt.The French consul Pierre Deval refused to give satisfactory answers to the Dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey touched the consul with his fan. Charles X used this as an excuse to break diplomatic relations. The Regency of Algiers would end with the French invasion of Algiers in 1830, followed by subsequent French rule for the next 132 years.xv

Beginning of the French occupation

On December 1, 1830, King Louis-Philippe named Duc de Rovigo as head of military staff in Algeria. De Rovigo took control of Bône and initiated colonisation of the land. He was recalled in 1833 due to the overtly violent nature of the repression. Wishing to avoid a conflict with Morocco, Louis-Philippe sent an extraordinary mission to the sultan, mixed with displays of military might, sending warships to the Bay of Tangier. An ambassador was sent to Sultan Moulay Abderrahmane in February 1832, headed by the Count Charles-Edgar de Mornay and including the painter Eugène Delacroix. However, the sultan refused French demands that he evacuated Tlemcen.xvi In 1834, France annexed as a colony the occupied areas of Algeria, which had an estimated Muslim population of about two million. Colonial administration in the occupied areas the so-called government of the swordxvii was placed under a governor-general, a high-ranking army officer invested with civil and military jurisdiction, who was responsible to the minister of war. Marshal Bugeaud, who became the first governor-general, headed the occupation. Soon after the occupation of Algiers, the soldier-politician Bertrand Clauzel and others formed a company to acquire agricultural land and, despite official discouragement, to subsidize its settlement by European farmers, triggering a land rush. Clauzel recognized the farming potential of the Mitidja Plain and envisioned the large-scale production there of cotton.xviii As governor-general (1835–36), he used his office to make private investments in land and encouraged army officers and bureaucrats in his administration to do the same. This development created a vested interest among government officials in greater French involvement in Algeria. Commercial interests with influence in the government also began to recognize the prospects for profitable land speculation in expanding the French zone of occupation. They created large agricultural tracts, built factories and businesses, and hired local labour. Among other testimonies, Lieutenant-colonel Lucien de Montagnac wrote on 15 March 1843, in a letter to a friend:

“All populations who do not accept our conditions must be despoiled. Everything must be seized, devastated, without age or sex distinction: grass must not grow any more where the French army has set foot. Who wants the end wants the means, whatever may say our philanthropists? I personally warn all good soldiers whom I have the honour to lead that if they happen to bring me a living Arab, they will receive a beating with the flat of the saber. This is how, my dear friend, we must make war against Arabs: kill all men over the age of fifteen, take all their women and children, load them onto naval vessels, send them to the Marquesas Islands or elsewhere. In one word, annihilate everything that will not crawl beneath our feet like dogs.”xix

The letter above shows the French attitude against the natives in Algeria. Whatever initial misgivings Louis Philippe’s government may have had about occupying Algeria, the geopolitical realities of the situation created by the 1830 intervention argued strongly for reinforcing French presence there. France had reason for concern that Britain, which was pledged to maintain the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, would move to fill the vacuum left by a French withdrawal. The French devised elaborate plans for settling the hinterland left by Ottoman provincial authorities in 1830, but their efforts at state-building were unsuccessful on account of lengthy armed resistance.xx

The capture of Constantine by French troops

The most successful local opposition immediately after the fall of Algiers was led by Ahmad ibn Muhammad, bey of Constantine. He initiated a radical overhaul of the Ottoman administration in his beylik by replacing Turkish officials with local leaders, making Arabic the official language, and attempting to reform finances according to the precepts of Islam. After the French failed in several attempts to gain some of the bey’s territories through negotiation, an ill-fated invasion force, led by Bertrand Clauzel, had to retreat from Constantine in 1836 in humiliation and defeat. However, the French captured Constantine under Sylvain Charles Valée the following year, on 13 October 1837.xxi

Historians generally set the indigenous population of Algeria at 3 million in 1830. Although the Algerian population decreased at some point under French rule, most certainly between 1866 and 1872, the French military was not fully responsible for the extent of this decrease, as some of these deaths could be explained by the locust plagues of 1866 and 1868, as well as by a rigorous winter in 1867–68, which caused a famine followed by an epidemic of cholera.xxii

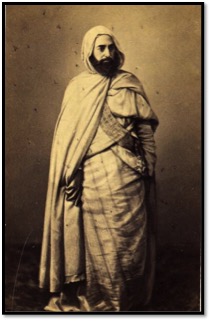

Emir Abd al Qadir

The French faced other opposition as well in the area. The superior of a religious brotherhood, Muhyi ad Din, who had spent time in jails for opposing the bey’s rule, launched attacks against the French and their makhzen allies at Oran in 1832. In the same year, jihad was declared and to lead it tribal elders chose Muhyi ad Din’s son, twenty-five-year-old Abd al Qadir. Abd al Qadir, who was recognized as Amir al-Mu’minin, quickly gained the support of tribes throughout Algeria.xxiii

He was also supported by the Ottoman Empire and even moved his family to Bursa, an Anatolian city. However, Emir Abd al Qadir always operated his plans between Damascus, Istanbul, and Algeria against French occupation in his motherland. A devout and austere marabout, he was also a cunning political leader and a resourceful warrior. From his capital in Tlemcenxxiv, Abd al Qadir set about building a territorial Muslim state based on the communities of the interior but drawing its strength from the tribes and religious brotherhoods. By 1839, he controlled more than two-thirds of Algeria. His government maintained an army and a bureaucracy, collected taxes, supported education, undertook public works, and established agricultural and manufacturing cooperatives to stimulate economic activity.

The French in Algiers viewed with concern the success of a Muslim government and the rapid growth of a viable territorial state that barred the extension of European settlement. Abd al Qadir fought running battles across Algeria with French forces, which included units of the Foreign Legion, organized in 1831 for Algerian service. Although his forces were defeated by the French under General Thomas Bugeaud in 1836, Abd al Qadir negotiated a favourable peace treaty the next year. The treaty of Tafna gained conditional recognition for Abd al Qadir’s regime by defining the territory under its control and salvaged his prestige among the tribes just as the shaykhs were about to desert him. To provoke new hostilities, the French deliberately broke the treaty in 1839 by occupying Constantine. Abd al Qadir took up the holy war again, destroyed the French settlements on the Mitidja Plain, and at one point advanced to the outskirts of Algiers itself. He struck where the French were weakest and retreated when they advanced against him in greater strength. The government moved from camp to camp with the Amir and his army. Gradually, however, superior French resources and manpower and the defection of tribal chieftains took their toll. Reinforcements poured into Algeria after 1840 until Bugeaud had at his disposal 108,000 men, one-third of the French army.xxv

By 1875, the French occupation was completed throughout the country. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830. A long shadow of genocidal hatred persisted, provoking a French author to protest in 1882 that in Algeria, “we hear it repeated every day that we must expel the native and, if necessary, destroy him” As a French statistical journal urged five years late, “the system of extermination must give way to a policy of penetration.”

French colonial policy in Algeria

Colonization and genocidal massacres proceeded in tandem in Algeria. Within the first three decades of the conquest, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Algerians, out of a total of 3 million, were killed by the French due to war, massacres, disease, and famine. Atrocities committed by the French against Algerians include deliberate bombing and killing of unarmed civilians, rape, torture, executions through “death flights” or burial alive, thefts and pillaging. Up to 2 million Algerian civilians were also deported in internment camps. During the Pacification of Algeria French forces engaged in a scorched earth policy against the Algerian population. Colonel Montagnac stated that the purpose of the pacification was to “destroy everything that will not crawl beneath our feet like dogs” The scorched earth policy, decided by Governor General Bugeaudhas, had devastating effects on the socio-economic and food balances of the country: “we fire little gunshot, we burn all douars, all villages, all huts; the enemy flees across taking his flock.” According to Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, the colonisation of Algeria lead to the extermination of a third of the population from multiple causes massacres, deportations, famines or epidemics that were all interrelated. Returning from an investigation trip to Algeria, Tocqueville wrote that “we make war much more barbaric than the Arabs themselves […] it is for their part that civilization is situated.”xxvi French forces deported and banished entire Algerian tribes. The Moorish families of Tlemcen were exiled to the Orient, and others were migrated elsewhere. The tribes that were considered too troublesome were banned, and some took refuge in Tunisia, Morocco and Syria or were deported to New Caledonia or Guyana. Also, French forces also engaged in wholesale massacres of entire tribes. All 500 men, women and children of the El Oufia tribe were killed in one night, while all 500 to 700 members of the Ouled Rhia tribe were killed by suffocation in a cave. The Siege of Laghouat is referred by Algerians as the year of the “Khalya”, Arabic for emptiness, which is commonly known to the inhabitants of Laghouat as the year that the city was emptied of its population. It is also commonly known as the year of Hessian sacks, referring to the way the captured surviving men and boys were put alive in the hessian sacks and thrown into dug-up trenches.xxvii

Towards independence

The French invasion was met with hostility, but the French were able to defeat the Ottomans. Approximately one third of the Algerian population died as a result of colonization, whether from direct warfare, disease, or starvation. Some governments and scholars have called France’s conquest of Algeria a genocide, such as Ben Kiernan, an Australian expert on the Cambodian genocide who wrote Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur on the French conquest of Algeria.xxviii

From May 8 to June 26, 1945, the French carried out the Sétif and Guelma massacre, in which at least 30,000 Algerian Muslims were killed. Its initial outbreak occurred during a parade of about 5,000 people of the Muslim Algerian population of Sétif to celebrate the surrender of Nazi Germany in World War II; it ended in clashes between the marchers and the local French gendarmerie, when the latter tried to seize banners attacking colonial rule. After five days, the French colonial military and police suppressed the rebellion, and then carried out a series of reprisals against Muslim civilians.xxix The army carried out summary executions of Muslim rural communities. Less accessible villages were bombed by French aircraft, and cruiser Duguay-Trouin, standing off the coast in the Gulf of Bougie, shelled Kherrata. Vigilantes lynched prisoners taken from local jails or randomly shot Muslims not wearing white armbands (as instructed by the army) out of hand. It is certain that the great majority of the Muslim victims had not been implicated in the original outbreak. The dead bodies in Guelma were buried in mass graves, but they were later dug up and burned in Héliopolis. During the Algerian War the French used deliberate illegal methods against the Algerians, including beatings, torture by electroshock, waterboarding, burns, and rape.xxx Prisoners were also locked up without food in small cells, buried alive, and thrown from helicopters to their death or into the sea with concrete on their feet. Claude Bourdet had denounced these acts on 6 December 1951, in the magazine L’Observateur, rhetorically asking, “Is there a Gestapo in Algeria?”. D. Huf, in his seminal work on the subject, argued that the use of torture was one of the major factors in developing French opposition to the war. Huf argued, “Such tactics sat uncomfortably with France’s revolutionary history, and brought unbearable comparisons with Nazi Germany.xxxi

Post-colonial relations

Relations between post-colonial Algeria and France have remained close throughout the years, although sometimes difficult. In 1962, the Evian Accords peace treaty provided land in the Sahara for the French Army, which it had used under de Gaulle to carry out its first nuclear tests (Gerboise bleue). Many European settlers (pieds-noirs) living in Algeria and Algerian Jews, who contrary to Algerian Muslims had been granted French citizenship by the Crémieux decrees at the end of the 19th century, were expelled to France where they formed a new community. On the other hand, the issue of the harkis,xxxii the Muslims who had fought on the French side during the war, still remained unresolved. Large numbers of harkis were killed in 1962 during the immediate aftermath of the Algerian War, while those who escaped with their families to France have tended to remain an unassimilated refugee community. The present Algerian government continues to refuse to allow harkis and their descendants to return to Algeria.xxxiii On February 23, 2005, the French law on colonialism was an act passed by the Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) conservative majority, which imposed on high-school (lycée) teachers to teach the “positive values” of colonialism to their students in North Africa. The law created a public uproar and opposition from the whole of the left-wing and was finally repealed by President Jacques Chirac (UMP) at the beginning of 2006, after accusations of historical revisionism from various teachers and historians.xxxiv

Algerians feared that the French law on colonialism would hinder the task of the French in confronting the dark side of their colonial rule in Algeria because article four of the law decreed among other things that “School programmes are to recognise in particular the positive role of the French presence overseas, especially in North Africa.” Benjamin Stora, a leading specialist on French Algerian history of colonialism and a pied-noir himself, said “France has never taken on its colonial history. It is a big difference with the Anglo-Saxon countries, where postcolonial studies are now in all the universities. We are phenomenally behind the times.” In his opinion, although the historical facts were known to academics, they were not well known by the French public, and this led to a lack of honesty in France over French colonial treatment of the Algerian people.xxxv

Current political problems between Algeria and France

The French national psyche would not tolerate any parallels between their experiences of occupation and their colonial mastery of Algeria. General Paul Aussaresses admitted in 2000 that systematic torture techniques were used during the war and justified it. He also recognized the assassination of lawyer Ali Boumendjel and the head of the FLN in Algiers, Larbi Ben M’Hidi, which had been disguised as suicides. Bigeard, who called FLN activists “savages”, claimed torture was a “necessary evil”. To the contrary, General Jacques Massu denounced it, following Aussaresses’s revelations and, before his death, pronounced himself in favor of an official condemnation of the use of torture during the war. In June 2000, Bigeard declared that he was based in Sidi Ferruch, a torture center where Algerians were murdered. Bigeard qualified Louisette Ighilahriz’s revelations, published in the Le Monde newspaper on June 20, 2000, as “lies.”xxxvi An ALN activist, Louisette Ighilahriz, had been tortured by General Massu. However, since General Massu’s revelations, Bigeard has admitted the use of torture, although he denies having personally used it, and has declared, “You are striking the heart of an 84-year-old man.” Bigeard also recognized that Larbi Ben M’Hidi was assassinated and that his death was disguised as a suicide. In 2018 France officially admitted that torture was systematic and routine.xxxvii

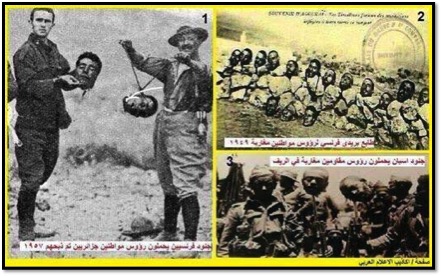

In 2017, President Emmanuel Macron described France’s colonization of Algeria as a “crime against humanity”. He also said: “It’s truly barbarous and it’s part of a past that we need to confront by apologizing to those against whom we committed these acts.” Polls following his remarks reflected a decrease in his support. In July 2020, the remains of 24 Algerian resistance fighters and leaders, who were decapitated by the French colonial forces in the 19th century and whose skulls were taken to Paris as war trophies and held in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, were repatriated to Algeria and buried in the Martyrs’ Square at El Alia Cemetery.

However, France will not apologize for its colonization of Algeria and will instead commemorate the violent history of its occupation of the North African country. “There will be no repentance, there will be no apologies,” an adviser to French President Emmanuel Macron said that ahead of the release of a much-anticipated report on the history of colonization and the Algerian War.xxxix

Notes

i MacLean, Gerald M. 2004. The rise of oriental travel: English visitors to the Ottoman Empire, 1580-1720. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

ii Simon, Rachel. 1987. Libya between Ottomanism and nationalism: the Ottoman involvement in Libya during the war with Italy (1911-1919). Berlin: K. Schwarz.

iii The term Dey from the Turkish honorific title dayı, literally meaning uncle, was the title given to the rulers of the Regency of Algiers.

iv Sessions, Jennifer E. 2015. By Sword and Plow: France and the Conquest of Algeria. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press

v Literally called ‘pieds noirs’ in French history.

vi It is called grands colons in French.

vii Ruedy, John. 1967. Land policy in colonial Algeria: the origins of the rural public domain. Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press.

viii Usually called as ‘royaume arabe’ in French colonial history.

ix Béni-oui-oui was a derogatory term for Muslims considered to be collaborators with the French colonial institutions in North Africa during the period of French rule.

x A similar law implemented White Skin Muslims if they want to classify as White in Apartheid South Africa between 1948 and 1994.

xi Christelow, Allan. 2016. Muslim law courts and the French colonial state in Algeria. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Pres.

xii They are both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or “Red Beard”. See, Bradford, Ernle, and Zehra Ağralı. 1970. Barbaros Hayrettin kaptan-ı derya Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa’nın hayatı. İstanbul Sander Yayınları.

xiii Kunt, Metin. 2014. An Ottoman imperial campaign: suppressing the Marsh Arabs, central power and peripheral rebellion in the 1560s (Bir Osmanlı sefer-i hümayunu: Ceza’ir-i Arab kalkışmasının bastırılması, 1560’larda merkezi güç ve uçlarda isyan). ISAM / 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi.

xiv Ayhan Afşin ÜNAL. 2002. “XVI.ve XVII.Yüzyıllarda Cezayir-i Bahr-i Sefid (Akdeniz, Ege Adaları) ya da Kapdan Paşa Eyaleti”. Erciyes Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. 1 (12): 251-261.

xv Gençoğlu, Halim. 2020. Türk arşiv kaynaklarında Türkiye – Afrika = Turkey – Africa in the Turkish Archival Sources. İstanbul SR Yayınevi

xvi Gordon, David C. 1966. The passing of French Algeria. London: Oxford University Press.

xvii In French ‘régime du sabre’.

xviii Clauzel, Bertrand. 1831. Observations du Général Clauzel sur quelques actes de son commandement à Alger. Paris: A.-J. Dénain.

xix De Montagnac, Lucien-François, and Élizé Louis De Montagnac. 2016. Lettres d’un soldat: Neuf années de campagnes en Afrique. Paris: BnF-P.

xx Ganimgil, Atilla Hakan. 2006. Gizli belgelerle Fransa’nın Cezayir soykırımı. İstanbul: Digital Kültür.

xxi Valée, Sylvain Charles. 1957. Correspondance du maréchal Valée, gouverneur général des possessions françaises dans le Nord de l’Afrique 5, 5. Paris: Ed. Larose.

xxii Gallois, William. 2008. The administration of sickness: medicine and ethics in nineteenth-century Algeria. Basingstoke [England]: Palgrave Macmillan.

xxiii Azan, Paul. 1925. L’Émir Abd el Kader 1808-1883: du fanatisme musulman au patriotisme français. Paris: Hachette.

xxiv Tlemcen was a vacation spot and retreat for French settlers in Algeria, who found it far more temperate than Oran or Algiers.

xxv Blunt, Wilfrid. 1947. Desert hawk: Abd el Kader and the French conquest of Algeria. London: Methuen.

xxvi Le Cour Grandmaison, Olivier. 2019. “Ennemis mortels”: représentations de l’islam et politiques musulmanes en France à l’époque coloniale. Paris: La Découverte, DL.

xxvii UCL – SST/ELI/ELIE – Environmental Sciences, Houyou, Zohra, Bielders, Charles, Dellal, Abdelkader, Boutmedjet, Ahmed, and Colloque international “Erosion éolienne dans les régions arides et semi-arides africaines: processus physiques, métrologie et techniques de lutte”. 2013. Impact de la céréaliculture en pluvial sur l’érosion éolienne à Laghouat Steppe algérienne°. http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/134112.

xxviii Valentino, Benjamin. 2000. “Final solutions: The causes of mass killing and genocide”. Security Studies. 9 (3): 1-59.

xxix Shabafrooz, Miriam. 2010. Oil and the Eruption of the Algerian Civil War: A Context-sensitive Analysis of the Ambivalent Impact of Resource Abundance. Series: GIGA Working Papers; No.118. Hamburg: German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

xxx As described by Henri Alleg, who himself had been tortured, and historians such as R. Branche.

xxxi. Lorcin, Patricia M. E. 2006. Algeria & France, 1800-2000: identity, memory, nostalgia. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

xxxii Harki is the generic term for native Muslim Algerians who served as auxiliaries in the French Army during the Algerian War of Independence from 1954 to 1962. The word sometimes applies to all Algerian Muslims who supported French Algeria during the war.

xxxiii Flood, Maria. 2019. France, Algeria and the moving image: screening histories of violence 1963-2010. Cambridge: Legenda, an imprint of the Modern Humanities Research Association.

xxxiv Chirac, Jacques. 1996. France and the new Euro-Asian partnership: speech given by Mr Jacques Chirac, President of the French Republic, Singapore, February 29, 1996. [Singapore]: [R. Brunet].

xxxv Stora, Benjamin, and Benjamin Stora. 1998. Algérie, formation d’une nation: suivi de, Impressions de voyage: notes et photographies, printemps. Biarritz: Atlantica.

xxxvi Hargreaves, Alec G. 2005. Memory, empire, and postcolonialism: legacies of French colonialism. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

xxxvii Stora, Benjamin, and Abdelwahab Meddeb. 2014. A history of Jewish-Muslim relations: Boston, Massachusetts: Credo Reference, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

xxxviii Hannoum, Abdelmajid. 2010. Violent modernity: France in Algeria. Cambridge, Mass: Center for Middle Eastern Studies of Harvard University Press.

xxxix France was the colonial power in Algeria for 132 years and Algerians won their independence in 1962, after a seven-year war marked by atrocities including acts of torture. This bloody history has overshadowed relations between the countries. As a presidential candidate, he called colonization a “crime against humanity” while on a visit to Algiers, which drew the ire of the far right. But since assuming office, he has not repeated the statement, even though he has said he fully stands by it. He has also overseen the return of the skulls of 24 Algerian resistance fighters decapitated during France’s conquest and kept as war trophies by French officers. Macron was also the first president to recognize that Maurice Audin, a French communist and anti-colonial activist who disappeared in Algeria in 1957, was “tortured then killed,” which was made possible by a “legally instituted system.” However, it seems that Macron will continue to play his political game with avoiding any positive action in order to genuinely resolve the issue between two countries France and Algeria. Otherwise, it seems France will continue to fight the ghosts of the Algerian War which French started.

Leave a Reply