The Armenian deportation of 1915 is one of the most politicized historical questions in the field and public sphere. Unfortunately, the historians who support the hypothesis of some Armenians that see the event as an effort at ‘genocide’ are not keen to consult archival sources regarding the issue, but rather repeat the same allegations from a political perspective. This is why the Armenian government did not accept President Erdogan;s offer to bring Armenian historians to Turkey to work in a mutual history commission regarding Armenian question. The invitation was rejected by the Armenian government because labelling the other side guilty seemed less risky than working on archival documents with Turkish historians.[1]

Turkish relations with Armenians in history

TheArmenian people of Anatoli are one of the oldest nations in Turkey. They are known as talented artisans and loyal to the Ottoman State. Ottoman archival documents show that Armenians lived under Ottoman rule for centuries in a peaceful society. However, in the late nineteenth century, like many other nations, Armenians started to rebel for independence.

Apart from archival documents, African newspapers from 1877 to 1917 highlight several points about the Armenian rebellion in Anatolia.

This news shows that Armenian were already provoked by the Russian Empire to attack Turks in the Ottoman-Russian War, 1877.

The Christian Express, 1 December 1876, ” Christians in Armenia”. p. 11, South Africa

According to the documents, the Russian Government provoked Armenians in 1877 and used them against the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War. Russians occupied an Ottoman province, Kars, with the assistance of Armenian soldiers. The occupation lasted more than 40 years. Loyal Armenians became an aggressive nation in Ottoman society. Radical Armenians even tried to kill the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid at Yıldız Mosque, in July 1905 in Istanbul; the Ottoman capital. The media described the incident as “one of the greatest and most sensational political conspiracies of modern times”.Belgian anarchist Edward Joris was among those who were arrested and convicted, but then released due to political pressure from Western states against the Ottoman Government. [2]

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation planned the assassination attempt on the Sultan to enact vengeance. Tashnak members, led by ARF founder Christapor Mikaelian, secretly started producing explosives and planning the operation in Sofia. 26 members of the Sultan’s service died. 58 from his service, as well as civilians in attendance, were wounded. 1905

Ottoman tolerance for minorities like Armenians or Greeks was not enough to sustain the unity of the Ottoman Empire. The minorities’ nationalistic sentiments and desire for autonomy became stronger than the multi-national harmony within the Ottoman society. Professor McCarthy explains the Ottoman tolerance for minorities as follows:

When the Ottoman Empire was struggling to reform itself and survive as a modern state, it was first forced to drain its limited resources to defend its people from slaughter by its enemies, then to try to care for the refugees who streamed into the empire when those enemies triumphed. After the Ottoman Empire was destroyed in WWI, the Turks of what today is Turkey faced the same problems: invasion, refugees, and mortality. Despite the historical importance of Muslim losses, it is not to be found in textbooks. Textbooks and histories that describe massacres of Bulgarian, Armenians, and Greeks do not mention corresponding massacres of Turks. The history that results from the process of revision is an unsettling one, for it tells the story of Turks as victims, and this is not the role in which they are usually cast. The Ottomans received little credit for their long and unique tradition of religious toleration. Ironically, they paid a heavy price for it. Foreigners used the excuse of protection of the Christian Millets and Christian brotherhood as pretexts for intervention in Ottoman internal affairs. Members of Christian Millets drew upon this sense of religious separation to create an anti-Ottoman nationalism.[3]

What really happened in 1915?

Levon Patnos Dabagyan, a Turkish historian of Armenian origin, noted that the “Armenian question was created as Russian policy but supported by almost all Western states against Turkey before 1915”. Indeed, Dabagyan’s statement remarkably explains a politized question so called Armenian Genocide.[4]

In fact, in order to establish an independent state in Anatolia, the Armenian nation revolted against the Ottoman State. It is reported in Turkish police reports that Tashnak and Hincak groups attacked civilians in Van, Muş and Erzurum. During the war, the Ottoman government had to defend and protect Muslim civilians and deported the Armenians to the Damascus province. There was no order of any systematic massacre of Armenians; it was clearly stated that the deportation order applies only to the rebellious ones.

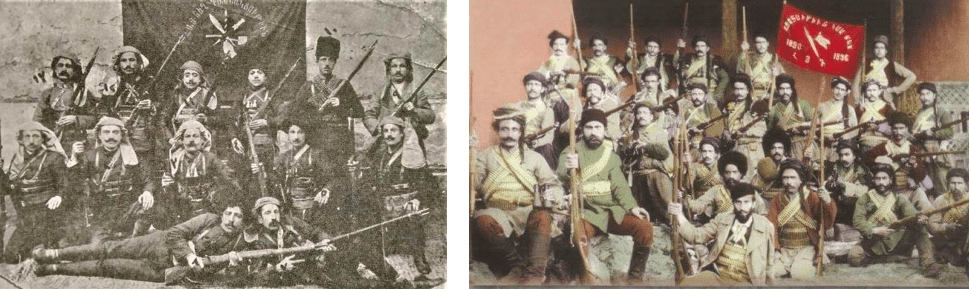

The Hinchak Committee in 1887 (left) and the Tashnak Committee in 1890 (right). Their terrorist activities disturbed the security in the region,which intensified over time and damaged the unity of the Ottoman Society.

What do the Ottoman archival documents say?

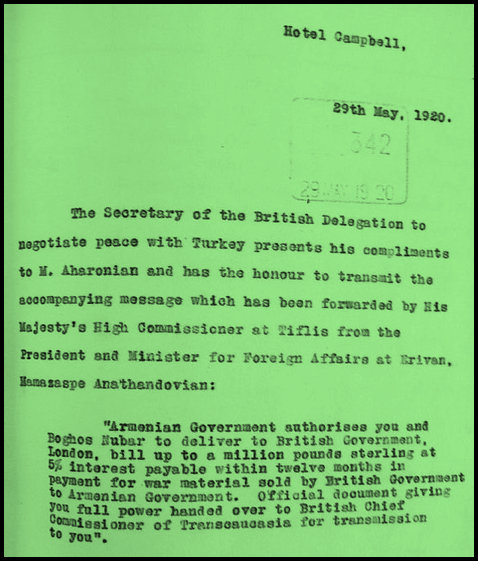

Archival records are the most valuable sources for us to understand the conflict between Turks and Armenians. According to archival documents, during the First World War, Armenian soldiers in the Russian Army attacked Turkish civilians in the Eastern frontiers. Turkish and Kurdish families were massacred by the Armenian soldiers. Ottoman police reports between 1914-1919 reported many Armenian crimes in Anatolia against Turkish civilians.[5]The clash between the Muslim people and the Armenians damaged the feelings of trust between the two communities.[6]However, publications like “the Blue Book” misrepresent the treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. This particular book was written by Viscount Bryce and Arnold J. Toynbee, first published in 1916, that contains a compilation of statements regarding Armenian issue from the British Government’s perspective. The correspondences between Armenian Government and British Government show the British policy in Asia Minor during the First World War.

An Archival document about British relations with Armenian Government in 1920. The document shows that the British were selling weapons to Armenians while British historians were writing “The Blue Book” in England.

Why is the term “Genocide” false?

Genocide is best understood as a systematic method of killing which intends to fully eliminate a people, nation, or ethnic group. Firstly, the Turkish nation has not believed itself to have racial superiority over minorities in history. There are many Armenian, Greek or Jewish people who served in the Ottoman Empire as commanders, viziers or medical doctors. Prof. Lewis stated that “the term ‘genocide’ is misleading because what happened to the Armenians did not happened to all Armenians. Relocations were limited to certain areas. Armenians living elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul and other cities away from the areas of relocation were not affected. There was no anti-Armenian ideology or propaganda comparable with the Nazi doctrines. Turkish complaint about Armenian was quite specific-that they were disloyal to the Ottoman Empire and were sympathizers or active supporters of Russia with which the Empire was at war. The Turks saw them as a security risk and therefore decided to remove them at whatever the cost from strategic and vulnerable areas in the Russian line of advance”. [7]

Some Armenian commanders in the Ottoman army (On the left: General Karabet Artin Davutyan)

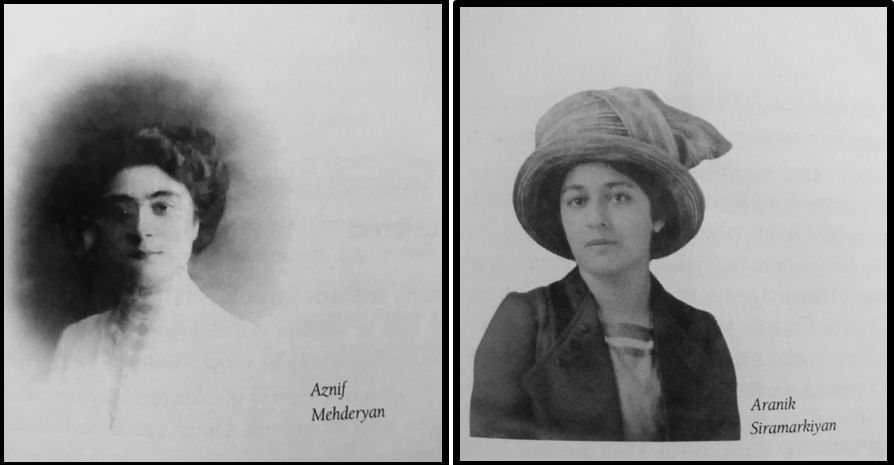

Indeed, at the time of deportation in 1915, several Ottoman Armenians were living in Istanbul and many Armenian students were sent to Europe for educational purposes. For instance, Ottoman students of Armenian origin Aznif Mehderyan and Aranik Siramarkiyan studied in Europe with an Ottoman bursary and became teachers in Istanbul in the 1920s. This begs the question: Why and how would such a tolerant state implement a genocide against an ethnic group which it had taken care and even provided equal access to resources such as education for centuries? The case of Armenian Question thus serves as a rhetorical question.

Ottoman students of Armenian origin Aznif Mehderyan and Aranik Siramarkiyan 1920s.

Armenians were never deported from Istanbul in spite of the Armenian rebellion. More importantly, many Armenian diplomats were working in the Ottoman’s foreign affairs sectors. They not only continued to work until the decline of the Empire, but also worked in the Republic of modern Turkey. For instance, Ottoman diplomat of Armenian origin, Leon Surenyan Effendi, received his silver medal when he was working as a Secretary of Foreign Affairs in Istanbul in 1915. He continued to work in the foreign ministry of the Ottoman Empire and received another award, Şir ü Hurşid,in 1919. After the decline of the Ottoman Empire, Leon Effendi started his new job in the Republic of Turkey in May, 1924. Another Ottoman diplomat of Armenian origin, Hrand Abro Bey, worked in the Ottoman government and was awarded with a gold medal in 1917. He retired and died in Istanbul in 1940. Similarly, Azak Effendi or Ohannes Effendi worked in the Ottoman Foreign Affairs Ministry between 1910 and 1920. Apart from Armenian diplomats, many Armenian families continued to live in Turkey during the WWI and also after the emergence of modern Turkey.

How many people died?

According to Ottoman archival records, 517,955 Turkish were killed by Armenians between 1916 and 1922. On April 19, 1915, Armenian irregulars attacked Muslim villages and killed 30,000 Muslims in Van. The Ottoman Empire was fighting against Britain, France, Italy, Greece and Russia at the same time. In order to stop their attacks, the Minister of Interior Affairs, Talat Pasha had to order the deportation of Armenians from Anatolia to the Damascus province on April 27, 1915.[8]While Armenians were deported from Anatolia, all the needs for Armenians such as transportation or food were prepared by the Ottoman government until the last station in Damascus. Girls between 20 and 30 and boys between 10 and 20 were excluded from the deportation. [9]Armenian deputies in the Ottoman parliament were also not exiled from Istanbul.

Similarly, Protestant and Catholic Armenians were not deported, because they had not joined the rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. According to American reports, 520,000 Armenians out of 1.2 million arrived in Damascus after the deportation.

700,000 Armenians died of illness and conflict during the First World War. In 1980, it was believed that 700,000 Armenians died in total. However, in 1990, the figure became 1 million, and in the 2000s it became 1.5 million. Professor Stanford Shaw noted that the Armenian rebellion destroyed the historical city Van and caused tremendous animosity between Turks and Armenians. Prof. Shaw’s house in Britain was bombed by Armenians extremists in the 1970s because of his statement against extremist Armenians. [10]

As such, the Armenian question was created by the West, but in a way that highlighted the Armenian betrayal towards the Ottoman government. Archival documents from Istanbul clearly highlight the Armenians extremists’ massacre in Anatolian villages in (year) as far as Caucasia. [11] However, in terms of civilian deaths among Armenians, the archival documents report that Armenian propaganda against Muslims.

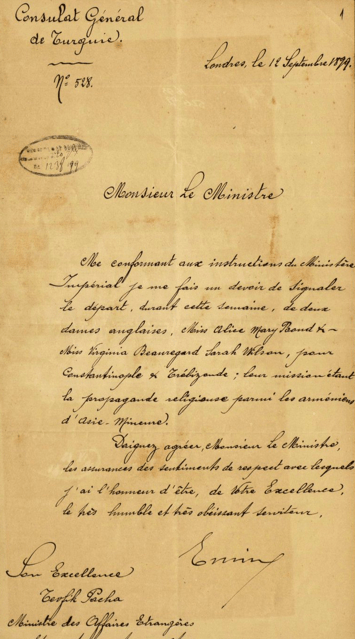

Two British women are being sent to Constantinople and Trabzon on a mission to spread religious ideas among Armenians in Turkey. 1899 (Ottoman State Archives)

There were plenty of Armenian musicians, artists and merchants in Turkey during the conflict between radical Armenians and Ottomans. For instance, the Turkish government sent a donation to Armenia in 1926. According to a Turkish archival document, 60,000 Armenian people became homeless due to the earthquake in Gyumri on October 22, 1926. Based on the report of Embassy in Moscow and Consulate in Gyumri, it is declared in the report of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, dated November 21, 1926 and numbered Political Relations 545, that it was decided that a certain amount of timber trees would be given to the Armenian Government for the construction of dilapidated houses in response to the friendship shown by the Soviet Government. It was deemed suitable to give two hundred tons of trees according to a report issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, dated Kanun al-Awwal 25, 1926. Even this attitude shows Turkish humanitarian sentiments towards the Armenian State.

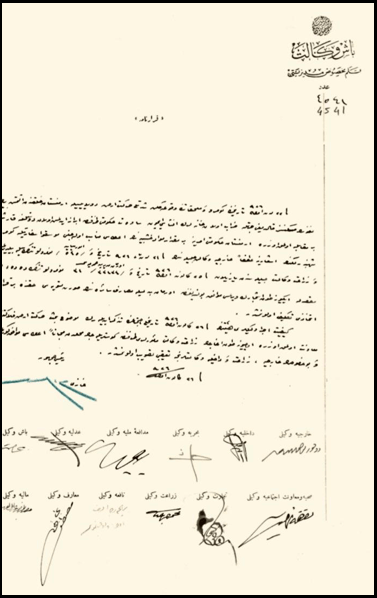

Sending 200 ton-timber trees to the Armenian Government as assistance for the victims of earthquake in Gyumri/Republic of Turkey Prime Ministry Private Office Number: 4541, December 26, 1926

A well-known Turkish classic musician of Armenian origin, Bimen Dergazaryan, was born in 1873 and died in Istanbul on August 26, 1943. He was one of the most popular musicians at the time of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and even received an honorary surname Şen (which means cheerful) from Atatürk himself. Similarly, Turkish opera singer Ruhi Su, Turkish actor Nubar Terziyan and Turkish photographer Ara Ruler were of Armenian origin and lived in modern Turkey. They were always loved by Turkish people and they rejected such a claim as “Armenian Genocide” in Turkey.

It is probably the most remarkable point made by a Turkish historian of Armenian origin, Levon Patnos Dabagyan, who stated that “most substantial proof against the so called “Armenian Genocide” is he himself, and that the claims of genocide are imperialist propaganda. [12]

Another matter brings a new dimension to the Armenian question. If Turks are “racist” as radical Armenians claim, then one could ask why they allowed so many Armenian diplomats and musicians to live in Turkey during the deportation; and why the Turks choose such a precarious period for the State, WWI, for the massacre for Armenians who had lived with Turkish people in the same territory for centuries. [13]

We might also ask why the Turks ignored Jewish and Greek and Suryani Christians, yet “killed” Armenians simply for being Armenians? These questions highlight some reasons why the Armenian genocide story has been fabricated for political goals. This political propaganda was created in order to establish an independent Armenian State, which was realized in 1918. Unfortunately, some western states like France and England also used this propaganda against Turkey, not only in their mainland but also in their colonies in Africa. Therefore, many old newspapers from Uganda, Nigeria or South Africa promoted the Armenian propaganda. However, ironically, while local people in Uganda were battling against poverty in the middle of Africa, the Armenian issue had, for some reason, even featured in the Ugandan newspapers in the 1900s. What could be the point of publishing Armenian news every week in Uganda, other than promoting Armenian propaganda.[14]

Conclusion

The Armenian question is a form of political propaganda on a global scale against Turkey. Even though France is known to have left behind a cruel legacy in Africa, one seldom talks of its massacres in Senegal or Algeria. Why does the Armenian issue cause such a stir in the former colonising country? On the one hand, France returns the skeletons of Algerian heroes to Algeria, on the other hand, it has a law that states “saying there was no Armenian genocide is a crime”. At the same time, one might wonder why France doesn’t discuss the massacres they orchestrated in Algeria where there were 1.5 million deaths. They even imprisoned British historian Bernard Lewis in Paris because of his statement in 1915 that the “Armenian conflict of Anatoli was not a genocide”. In fact, Armenian hypotheses contradict archival documents.

The Armenian question needs to be studied by honest historians. If a historical matter is tossed around like a ball bouncing between France to Germany; from Uganda to America, it should be clear it has already been subject to broader politics. For this reason, instead of studying the real reasons for the deportation in the Ottoman archives, Armenian historians prefer to use secondary Western sources regarding the Armenian-Ottoman conflict in Anatolia. Thus, a historical question has been politicized and become the basis for international propaganda against Turkey.[15]

[1]Armenian issue exploited to blackmail Turkey, President Erdoğan says, https://www.dailysabah.com/diplomacy/2016/06/04/armenian-issue-exploited-to-blackmail-turkey-president-erdogan-says, accessed 19. 07. 2020.

[2] ALLOUL, H., ELDEM, E., & DE SMAELE, H. (2018). To kill a sultan: a transnational history of the attempt on Abdülhamid II (1905).London (GB), Palgrave Macmillan.

[3] MCCARTHY, J. (2014). Death and exile: the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Muslims 1821 – 1922. P. 6,8. Princeton, New Jersey Darwin Press

[4] DABAĞYAN, L. P. (2007). Emperyalistler kıskacında Ermeni tehciri. Cağaloğlu, İstanbul, IQ Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık.

[5] https://www.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/varliklar/dosyalar/eskisiteden/yayinlar/osmanli-arsivi yayinlar/arsiv_belgelrine_gore_kafkaslarda_ve_anadoluda_ermeni_mezalimi_3_1919_1920-(tıpkıbasım).pdf, accessed in 2020. 07. 18.

[6] Halim Gencoglu, Afrika basınında Ermeni meselesi (1876-1922) https://www.aydinlik.com.tr/afrika-basininda-ermeni-meselesi-1876-1922-ozgurluk-meydani-aralik-2019, accessed in 2020. 07. 18.

[7] LEWIS, B., & CHURCHILL, B. E. (2013). Notes on a century: reflections of a Middle East historian,New York: Penguin Books

[8] Ottoman State Archives, DH ŞFR, Nr: 3822

[10] https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1982/05/17/armenian-terrorism/2b448a6c-20ab-452f-89dc-af7e2282557d/), accessed, 23.07.2020.

[11] See, Arşiv Belgelerine Göre Kafkaslarda ve Anadolu’da Ermeni Mezalimi, T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri, Yayın No: 23, 24, 34, 35.

[12] DABAĞYAN, L. P. (2007). Emperyalistler kıskacında Ermeni tehciri I: Türk Ermenileri. Istanbul, IQ Kültür Sanat.

[13] MEHMET PERINÇEK. (2018). The 1915 Events In The Light Of The Russian Archives And International Court Decisions. Review of Armenian Studies.117-148.

[14] DABAĞYAN, L. P. (2010). Tarihin ışığında Ermeni meselesi ve 1915 kaosu. İstanbul, Yedirenk.

[15] It is likely that Armenians will not accept to study on Armenian-Turkish conflict of 1915 with Turkish historians, not only for Armenian Genocide is a historical lie of the 20 century but also Armenian Diaspora makes amazing profit out of Armenian genocide claims as an organization which is also admitted by the minister of Armenia. See, Why Armenians are successful everywhere except Armenia said, Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/why-armenians-are-successful-everywhere-except-armenia/, accessed in 2020. 07. 18.

Leave a Reply