The history of Ottoman Jews in Asia Minor, particularly the Sephardim, began when they migrated to Turkey from Europe after the Alhambra decree in Spain of 1492. After the fall of Andalusia, today Spain, Jews struggled to continue living not only in Spain, but also encountered difficulties in other European countries in the late fifteenth century.[i] Eventually, the Sephardim (in Turkish, Sefarad) were forced to move out of Spain.[ii] By the order of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II, an imperial decree was issued in order to help the Jews in Spain and the Western world.[iii] Sultan Bayezid II sent a naval force to the Mediterranean under the command of Captain Kemal Reis and thereupon Ottoman general Kemal Reis gathered most Jews from Spain and brought them to Istanbul.[iv] First Sephardim Jews, later Ashkenazi and then Marronos settled down all over the Ottoman land but especially, Istanbul, Izmir, Salonika and Edirne.[v]

Jewish People in the Ottoman World

Ottoman Jews have lived more than 500 years in the Ottoman territory and following the Ottoman Russian War, in 1877-78, after the Ottomans were defeated by Russia, some Jews began to seek a new beginning in other continents as well as in Africa. From this particular time to the second world war, some Ottoman Jewish families thus moved to Southern Africa and settled in Salisbury, Johannesburg and at the Cape of Good Hope. This paper aims to reveal this neglected jewish community in South African history.

Ottoman – Jewish relationships in history

The Ottomans initially established a bridgehead in Anatolia in the 1300s, and then expanded relentlessly from there through south-eastern Europe all the way to Danube. They had bypassed Constantinople but under Mehmet II finally conquered the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire in 1453, continuing their campaigns under Selim I with the capture of Syria and Egypt. As its peak of expansion, the Empire encompassed approximately 250,000 Jews. Her sultans, Mehmet II, Yavuz Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent were dynamic, farsighted rulers who were delighted to receive the talented, skilled Jewish outcasts of Europe.[vi] When the Ottomans took over Edirne, the Jewish population living in surrounding regions also immigrated to the city. An Ottoman Jewish intellectual, Professor Abrams Galantine, author of the book Turks and Jewish gives an eyewitness account of the Jewish history as a Jewish historian,

The arrival of Turks [in Asia Minor] meant a lot to Jewish communities located in the area. It immediately changed the conditions surrounding their lives. As opposed to Europe, they found genuine equality and freedom under Ottoman rule. The Jewish considered the Turks not as conquerors but as brothers due to similarities in both religions. On the other hand, Jewish people were highly trusted by the Turks, because their religion carried concepts such as the simplicity of holy places, fasting and circumcising of children which are not very different from the ones in the Muslim religion.[vii]

As it is also indicated above, Ottoman Jews played a prominent role in the social-economic context and developed the banking system in the Ottoman State.[viii] One of the most significant innovations that Jews brought to the Ottoman Empire was the printing press. In 1493, only one year after their expulsion from Spain, David and Samuel ibn Nahmias established the first Hebrew printing press in Istanbul.[ix]

Additionally, Ottoman diplomacy was often carried out by Jews. Joseph Nasi, appointed the Duke of Naxos, was the former Portuguese Marranos Joao Miques. Another Portuguese Marranos, Alvaro Mendes, was named Duke of Mytylene in return for his diplomatic services to the Sultan.[x] Salomon ben Nathan Ashkenazi arranged the first diplomatic ties with the British Empire. Jewish women such as Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi “La Seniora” and Esther Kyra exercised considerable influence in the Ottoman Court.[xi]

Ottoman archives provide further information for us to better understand the general situation of Jews during the Ottoman period.[xii] Due to antisemitism against Jews in Western World, sometimes christians and jewish communities had religious conflicts in the Ottoman Empire. For instance, “Blood Accuation” was one of the most problematic allegations for jews people in history and according to this rumor, jewish killed and sacrificed christian children in passover because of a prophecy. On October 27, 1840 Sultan Abdulmecid issued his famous decree (ferman) concerning the “Blood Label Accusation” saying: “… and for the love we bear to our subjects, we cannot permit the Jewish nation, whose innocence for the crime alleged against them is evident, to be worried and tormented as a consequence of accusations which have not the least foundation in truth…”[xiii]

Although Ottoman Empire was an Islamic State, the sultans never showed more tolerance to their co- religionists for better opportunities in the society. One of the court cases shows remarkable tolerance towards jewish people in the empire. Religious day of Jewish in the week, basically, Saturday became a problem in izmir city because two Ottoman jewish could not attend the public market in Saturday to sell their goods. Thereupon, they applied to the Ottoman governor in the city and magistration court eventually changed the day from Saturday to Tuesday for public market. This kind of administration understanding was valid for all the minorities in the Ottoman Empire. In several imperial decrees, Ottoman Sultans involved social affairs in order to provide better ruling throughout Empire.

This solidarity between different nations and religions coursed a remarkable attachment in the Ottoman society. So that, in 1892, Ottoman Jews commemorated their 400 years since their arrival on the Ottoman soil and their peaceful life in a Muslim state. After the Ottoman Russian war, Ottomans lost their northern provinces, Moldova and Romania (Eflak- Bogdan), and many Jews had to move to Turkey.[xiv] During the Ottoman Russian War, an Ottoman jewish citizent Ishak Pasha attended the Ottoman Russian Campnaigs and served successfully as an Ottoman General.

During the Ottoman Russian War in 1877-1878, Ottoman Empire lost its provinces Moldovia and Romania and Polonies (Eflak – Boğdan, Lehistan) in northwest frontiers. The result of this battle did not only affected Ottoman State but also the Jewish minorities who lived in northern side of Black Sea under the Ottoman rules for centuries. After the Russian occupation, Jews citizen were forced to live their homeland. Ottoman archival sources highlight the issue in detail that shows how Russian badly treated to Jewish in order to let them leave the territory.[xv] Interestingly some of them moved to South Africa too. There are a number of Ottoman Jewish families in South Africa amongst whom previous generations could speak Turkish.

Ottoman Jewish in South Africa

The migration of the Ottoman Jewish from Ottoman territories to Southern Africa began in the nineteenth century when Ottoman Empire lost the war against Russia and jewish were running away from the Russian borders. The Jewish community mostly moved to countryside of the Ottoman state but some of them wanted to have a new beginning in different continents. That’s how some jewish families moved to South Africa in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Due to multi language skills, ottoman jews were well connected with other jewish communities in the world. The South African Jews society of the nineteenth century was also aware of the barbaric treatment of Russian soldiers in spite of the lack of communication despite great geographic distinct. According to South African local news, during the Ottoman Russian War, Ottoman War prisoners were treated badly and feed with pork.[xvi] On the other side, South African Standard and Mail proclaimed an interesting charity to gathered financial aid for the Ottoman Jewish in Bulgaria and Russia. The news remarkably reveals the general situation of Ottoman Jews as the following correspondence below will show the distressing position of the sufferers from that desolating war:

I am informed that amongst the Fugitives who have arrived at Adrianople (Edirne) and elsewhere are number of Jewish Families who have suffered almost as much as the Muhammadans from most cruel treatment at the bands of the Bulgarians and Russians. They are chiefly from Eski Sangha and Kısanlık (Eski Sahra and Kızanlık in Turkish, suburbs) at the latter place many Jews are stated to have been massacred. Turkish authorities have done their best to protect them and many of Fugitives have assured him that the Turkish regular troops treated them kindly gave them their own blankets and cloaks for their children. One Jewish girl of 18, years of age died from the outrages… These poor Jews persecuted by Christians and helped and protected by the Muhammadans alone are in the greatest misery… I am directed by the Early of Derby to transmit to you a copy of a dispatch from her majesty’s ambassadors at Constantinople, relative to the sufferings of a number of Jewish families who have fled from their villages and have arrived at Adrianople and other towns in Romania. … In compliance with the earnest request of the London Jewish Board of Deputies and the Anglo Jewish Association, the Reds, Samuel Hardey and Joel Rahnowitz beg most respectfully to appeal to the generous public of South Africa for aid to alleviate the dire distress of the inhabitants of the Turkish Empire, caused by the War which is now raging in that Country. Thousands of families have been deprived of all their worldly possessions and are now without shelter and food. .. The found collected will be distributed by an independent Board in conjunction with lady Burdett Coutts and lady Strangford to all the sufferers without distinction of creed or nationality.[xvii]

Synagogue Chambers, Cape Town

October, 22nd. 5638. 1877

As mentioned earlier, in the second quarter of the twentieth century, Jewish people were still suffering because of the implementation of anti-Semitic western policies in Europe. The Ottoman Russian war was a turning point of the Ottoman jewısh and theır migrations to other continents as far as Afrika. Therefore, Separdim jews migrated to other states to survive in better conditions.

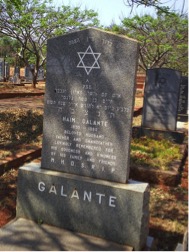

An Ottoman Jewish benefactor Haim Galante in South Africa

In 1890, the mine industry began to develop gold and diamond fields in South Africa. These economic developments acted as a catalyst for the Anglo-Boer campaign’s colonial powers in the territory. Ottoman jews who were expert in the field of jewelry, were interested to use this opportunity for their profession.[xviii] Like Ottoman jewish, Haim Galante, several sephardim families decided to move to Southern Africa.[xix] Firstly Moses and Gabriel Benatar from Rhodes island moved to Salisbury in 1895. From the same family, Solomon Benatar moved to Kongo from Rhodes in 1905. On the other hand, the family archives prove that the Ottoman jewish still used the Turkish fez in South Africa despite the territorial distance. Profesor Ralph Tarica stated that, many religious scholars like Rabbi Avraham Tarica and Rabbi Mosheh HaCohen lived in peace in Rhodes island from 1652.[xx] According to Ralph, another part of the Tarica family lived in Izmir city as welknown attorneys and accounters until they settled in Southern Africa.[xxi] In the same way, Haim Galante settled in Salisbury but Ottoman archival documents show that he had a close relationshipwith the Ottoman Government when he was living in Rhodessa.

Haim Galante was known as prominent leader in jewish circles. He rapidly established remarkable relations with muslims who were already attached to the Ottoman caliphate due to religious affairs. According to a Turkish archival source, Haim Galanti gathered donations from the jewish and muslim community in South Africa.[xxii] The most populer Ladino journal called “El Tiempo of Constantinople” notedthatgalante collected donations from muslims and jewish in Natal, Juhannesburg, Cape Town and sent them for the ottoman navy.[xxiii] With the donations, Haim Galanti Efendi’s letter clarified jewish relations with the Ottoman State.

His Excellency,

In order to support our navy, I gathered some money from the Indian Muslim community and the Ottoman Jewish in South Africa and it is a honor for me to send the amount of 27 thousands British pounds as a bank paper. In this region, muslim indians are very grateful to contribute to the Ottoman naval in this difficult days for our state. We, the ottoman jewish are always very thankful to the Ottoman administration. Thank goodness with the help of the Hamdiyye warship, Edirne city is rescued from the Russian attack. We always desire to see the Ottoman state in good conditions.[xxiv]

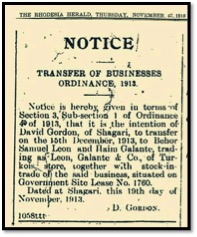

As it is understood from these sentences above, Galante Effendi did collect remarkable donations for the Ottoman Navy because the Ottoman Naval force had saved the city Edirne where mostly jewish people lived during the Ottoman period. This important letter is sufficient evidence to understand the positive relations in Ottoman Empire. In spite of great distance to the Ottoman territory, Jews in Southern Africa supported the Ottoman state durng the Ottoman Russian Wars.[xxv] Therefore, Turkish Jews in South Africa sent donation to the Ottoman state from Salisbury and thus showed their support to the Ottoman Sultans.[xxvi] As a prominent jewish leader, Haim Galante Effendi also named his business primacies as Turkoise Mine or Turquoise Tennis Club, another fact that also indicates his attachment to his country.[xxvii]

Additionaly, another important matter proves the significance of Ottoman – Jewish relationship in history. During the Balkan war, Turkish Jews in South Africa protested and boycotted Greek nationalist rebellions and supported the ottoman state. This was reported to British Empire and by the order of colonial government in South Africa, Jewish in Salisbury were arrested by police force. Thereupon, Turkish Jews in Salisbury sent a letter to chief rabbi in Johannesburg in order to resolve this unfair treatment. Chief Rabbi took a risk for Turkish Jews and declared that all responsibility belongs to him in condition of release these Jewish citizens in Salisbury. Turkish Jews were only released on condition of signing a paper in the police station every day during the war.[xxviii] In the same year in Anatolia, ottoman Jews strictly defended the Turkish Empire and when Greek occupied Izmir they were also killed by Greek soldiers. Christians always hated Jews, but they also did so specifically because Jews were attached to Turks like an ancient friend of the same destiny, as jewish historian stated.[xxix]

Even after the first world war, when Istanbul was occupied by British Empire, France and other allies, the British Empire employed Ottoman Greek and Armenian translators to communicate with Turkish soldiers in 1919. In spite of their multi-language skills, the British did not employ Jews as translators because they knew that Jews were totally against the British occupation in Turkey.[xxx] Even after the war, Jews always supported Turks even during the Lausanne treaty in 1923.[xxxi]

Besides that, after the decline of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Jews contributed to the emergence of modern Turkey. The founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, supported the Jewish community not only in the new industrial sectors, but even in state affairs.[xxxii] In one of his speeches, he stated that; we have some non-Muslim citizens who attached their destinies with Turks. Especially the Jewish people have proven their loyalty to this state and they lived in peace under the Ottoman rule, and will live in welfare and happiness after this as well.[xxxiii]

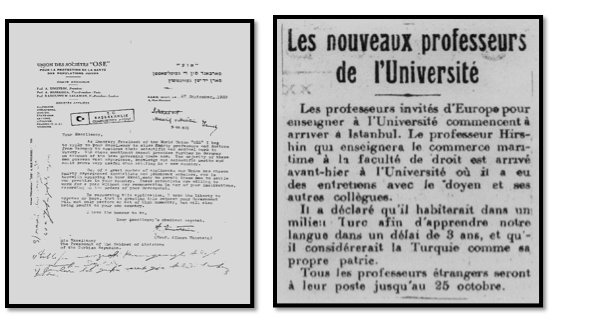

During that period, Germany occupied a Turkish island, Rhodes which was mostly inhabited by Sephardim Jewish that migrated to Turkey from Spain. The Turkish consulate of Rhodes Island, Selahattin Ülkümen was a Turkish diplomat during the Second World War in Rhodes. Turkish and Greek Jews alike were deported to death camps from the island of Corfu but on the island of Rhodes, Turkey’s Consul, Selahattin Ülkümen, saved the lives of close to 50 people, among a Jewish community of some 2000 after the Germans took over the island. Jews had prospered on Rhodes during 390 years of Ottoman rule until 1917, and under the succeeding Italian occupation until 1943, when the Germans took over. By the 1940s, the ethnic Jewish community numbered about 2000, made up of people from Turkey, Greece, Italy and other Mediterranean countries, as well as those native to the island. After the German occupation, Ottoman Jewish people could not stay in Rhodes Island anymore and moved other countries. While some Jewish moved to Istanbul, others migrated to South Africa and Argentina. During the tragic days of World War II, Turkey managed to maintain its neutrality. As early as 1933, Ataturk invited numbers of prominent German Jewish professors to flee Nazi Germany and settle in Turkey.[xxxiv]

Before and during the war years, these scholars contributed a great deal to the development of the modern Turkish university system.[xxxv] Additionally and more importantly, in 1934, by the request of great scientist Albert Einstein, 40 great Jewish scholars were accepted at universities in Turkey.[xxxvi]

Several Ottoman Sephardim Jewish of Rhodes island now live in Cape Town with Turkish traditions. As an old tradition, they still offer Turkish coffee and Turkish delight to their guests on special occasions. They express their gratitude towards the judicious administration of Ottoman Empire. The head of the Sephardim Jewish community, Osvalto Sultani states that “if we didn’t have the Ottoman passport we wouldn’t reach Argentine and other countries in our immigration.” Maurice Sauriano, the head of the 35-person Jewish community who remained in Rhodes after the war, recently stated that he is “indebted to the Turkish consul who made extraordinary efforts to save my life and those of my fellow countrymen.” In retaliation, German planes bombed the Turkish consulate on Rhodes. Killed in the bombing was Ülkümen’s pregnant wife Mihrinissa Ülkümen, as well as two consular employees. The Germans quickly detained and deported Ülkümen to Piraeus on mainland Greece and confined him there for the remainder of the war.[xxxvii]

Finally, early in January 1945, the German commander Kleeman learned that representatives of the International Red Cross were to visit Rhodes to look into the situation of its population. He ordered the remaining Jews on the island to go to Turkey, which they did the next day, traveling in small boats across a stormy sea to safety at the port of Marrnaris. The German occupation followed Benito Mussolini’s defeat in Italy and its armistice with the Allies. After the German occupation, Ottoman Jewish people could not stay in Rhodes Island anymore and moved other countries. While some Jewish moved to Istanbul, others migrated to South Africa and Argentina.

Conclusion

The foregoing story is somewhat evocative of a development four-and-a half centuries earlier. The Ottoman Empire had always been a polyglot, multiracial country, with wide religious tolerance. The Empire’s footprint at its peak resembled that of Rome at its peak, including Anatolia, the Middle East, the Balkans, North Africa, and lands ringing the northern coast of the Black Sea. In the 16th century the Mediterranean was referred to as the “Ottoman Lake.” In 1492, Spain, fresh from expelling the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula, made it clear to the Jews they were no longer welcome: “convert or leave!” The resulting Jewish exodus led in two directions, east to the Ottoman Empire and northeast to Eastern Europe.

Likewise some Ottoman Jewish immigrated to South Africa from Rhodes Island during the Second World War. This small Sephardim Jewish community in Sea Point is not only aware of its historical background but the old generations can still speak Turkish. They say that their favourite food is still the Turkish kebab which is one of the common links between Sephardim Jewish and Turks in present day South Africa.

Notes

[i] In 1394, due to anti-Semitic events against Jewish in France, Ottoman Rabbi (Hahambasi) Isak Sarafati called Jews to Turkey as “from the shadow of cross to the shadow of crescent”.

[ii] In the beginning of Turkish control in Mediterranean, Jews Armenian and Turkish merchants replaced the Venedik- Ceneviz merchants in the territory. Halil inalcik, 2015, Devlet-i Aliyye, Osmanlı imparatorluğu üzerine Araştırmalar, p. 310, Istanbul

[iii] Appendix III. The document illustrates the satisfaction and gratefulness of the Ottoman Jewish on Ottoman territory for 400 years, 1892.

[iv] In Balkan territory, Serbian, Jewish and Greek tax assessor worked in the era of Fatih Sultan Mehmet under the Ottoman Rule. See, Halil inalcik, 2015, Devlet-i Aliyye, Osmanlı imparatorluğu üzerine Araştırmalar, p.243 istanbul

[v] Settled Jewish to Ottoman territory according to the Ottoman registration book. See, Ottoman State Archives, C. İKTS. 29/Z/1255 (Hijree) No: 22/1059

[vi] Uzuncarsili Ismail Hakkı 1987, Osmanlı Tarihi, volum II . P. 203. Ankara

[vii] Galanti Avram, 1947 Türkler ve Yahudiler, (Turks and Jewish) Page 9, Istanbul

[viii] Gerber Haim, 1981, Jews and Money-Lending in the Ottoman Empire, The Jewish Quarterly P. 101.

[ix] Yunus Özger, 2011, Sicili Ahval Defterlerine Göre Bazı Yahudi memurlarının sosyo kültürel durumları, P, 3

[x] Gershon Scholem Sabbatai Sevi, the Mystical Messiah 1629- 1676 Page 121. ( Princeton, 1973)

[xi] Eroglu Ahmet Hikmet,1997 Osmanlı Devletinde Yahudiler, (Jewish in Ottoman State) Page 104, Ankara

[xii] Ottoman State Archives; YA, Hususi, 1312, 10/13, 323/129, The document is related the court case on Jewish Passover. According to the document Jewish kidnaps a child to drink his blood in this holy day and for this gossip Sultan Abdulmejid issued a decree to protect the Ottoman Jewish.

[xiii] Ottoman State Archives, Irade Adliye Mezahip, 1310 No; 20.

[xiv] Ottoman State Archives; YA, Hususi, 1309, 10/17, 206-112 -1, The document illustrates the satisfaction and gratefulness of the Ottoman Jewish on Ottoman territory for 400 years, 1892

[xv] Ottoman State Archives, Y. PRK. AZJ. No: 55/88, Rusya Devleti tarafından Sürgün edilen yahudilerin Suriye topraklarında arazi istemeleri (Regarding some persecuted Jewish from Russia to Ottoman land and their request to have some land in Syria) See also, Ottoman State Archives, C. İKTS. 29/Z/1255 (Hijree) No: 22/1059 Lehistandan çıkıp Türkiyeye ceste ceste gelen Yahudilerin terki vatan etmeleriinin sebep ve hikmeti hakkında tahkikatı mutazammın Buğdan Kapı kethüdası tarafından. (Regarding the helping Jewish refugees who are treated badly by Russian and therefore immigrate from Belarus (Lehistan) to the Ottoman province Boğdan (Moldavia)

[xvi] The Standard and Mail, Tuesday, June, 5, 1877 (Our Portfolio,) The Uitenlage Malays are greatly exercised in respect of the Turkish – Russian War. They have had special services at the Mosque for the last week or so, praying for the success of the Turks. On receipt of the last telegram, some wiseacre informed them that the Russians had taken 17.000 Turks prisoners and were feeding them on nothing but pork. The Malay were horrified at the supposed enormity and immediately had all the services doubled. P. 3

[xvii] The Standard and Mail, Tuesday, October, 23. 1877 Turkish Sufferers Relief Fund….)

[xviii] Louis Herrman, 1930, A History of the Jews in South Africa, from the earliest times to 1895, s. 274. London

[xix] Richard Mendelshon- Milton Shain, 2008, The Jews in South Africa. S. 182 Cape Town

[xx] Ayr. Bkz. http://www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org/museum/family-photos

[xxi] Ralph Tarica, 2000, In Search of the Family Name Tarica: A Genealogical Adventure, s 8

[xxii] BOA, BEO 4180/313427 Hicri, (29/C/1331)

[xxiii] Nathan Shachar, 2013 The lost Worlds of Rhodes, Greeks, İtalians, Jews, and Turks between Tradition, s.73. England

[xxiv]“Buradaki küçük Hint cemaati Islamiyesinin sevgili vatanımıza karşı hissiyati mevcudiyet perverlerini uyandırmak için calışmaktan geri kalmadım. Biz Osmanlı Musevilerinin Türkiye’ye olan muhabbetlerinin derecesi fevkeladedir. Son muharebenin gavailini Kemal-i ihta ile takip ederek vatani azizimizin felaketine iştirak ettik. Edirnenin istirdadı bizim için mucibi teselli olduĝu gibi Hamidiye Kruvazörü Humayununun kahramanlıĝı dahi ayrıca maddei ihtiharım olmuştur. Memleketimizin ila ve saadeti hali uĝrunda daimi temenniyatta bulunmakta kusur etmiyoruz.. Selahattin özçelik, 2000, Donanmayi Osmani Muaveneti Milliye Cemiyeti, s. 213 Ankara Ayr, Bkz. Ahmet Uçar, 2008, Güney Afrika’da Osmanlılar, s. 537 Istanbul.

[xxv] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p. 67, 70 istanbul

[xxvi] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p. 67, 70 istanbul

[xxvii] The Rhodesia Herald, Tesday, December 23 , 1919, see also, http://www.rhodesjewishmuseum.org/museum/family-photos)

[xxviii] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p.79 istanbul

[xxix] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p. 58 istanbul

[xxx] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p.79 istanbul

[xxxi] Avram Galanti, 1947, Türkler ve Yahudiler, Tan matbaası, p. 67 istanbul

[xxxii] For Instance, one of the Ottoman Jew and anti-Zionist, Rabbi Haim Naum was appointed to go to Lozan treaty by the order of M.K Ataturk in 1923. See, Dünden Bugüne İstanbul Ansiklopedisi, Vol. 6, Page. 27-28, TC Kültür Bakanlığı ve Tarih Vakfı 1994

[xxxiii] Turkish Newspaper, Saday’ı Hak ve Anadolu. 3 Şubat 1923

[xxxiv] Horst Widmann: 1973, Exil und Bildungshilfe. Die deutschsprachige Emigration in die Türkei nach 1933. Mit einer Bio-Bibliographie der emigrierten Hochschullehrer im Anhang Peter Lang, Frankfurt

[xxxv] Reisman Arnold 2007, Jewish Refugees from Nazism, Albert Einstein, and the Modernization of Higher Education in Turkey (1933–1945) No. 7 p. 266 Selahattin Ulkumen was the Turkish consul-general on the island of Rhodes which was under German occuaption. In late July 1944, the Germans began the deportation of the island’s 1,700 Jews. Ulkumen managed to save approximately 50 Jews, 13 of them Turkish citizens, the rest with some Turkish connection. In protecting those who were not Turkish citizens, he clearly acted on his own initiative. In one case, survivor Albert Franko was on a transport to Auschwitz from Piraeus. Whilst still in Greek territory, he was taken off the train thanks to the intervention of Ulkumen, who was informed that Franko’s wife was a Turkish citizen. Another survivor, Matilda Toriel relates that she was a Turkish citizen living in Rhodes and married to an Italian citizen. On July 18, 1944, all the Jews were told to appear at Gestapo headquarters the following day. As she prepared to enter the building, Ulkumen approached her and told her not to go in. It was the first time she had ever met him. He told her to wait until he had managed to release her husband. As her husband later told her, Ulkumen requested that the Germans release the Turkish citizens and their families, who numbered only 15 at the time. However, Ukumen added another 25-30 people to the list whom he knew had allowed their citizenship to lapse. The Gestapo, suspecting him, demanded to see their papers, which they did not have. Ulkumen however returned to the Gestapo building, insisting that according to Turkish law, spouses of Turkish citizens were considered to be citizens themselves, and demanded their release. Matilda later discovered that no such law existed, and that Ulkumen had simply fabricated it in order to save the Jews. In the end, all those on Ulkumen’s list were released. All the rest of the Jews on the island, some 1,700, were deported to Auschwitz.

[xxxvi] Hungarian musician Licco Amar, Chemist Fritz Arndt, writer Erich Auerbach, economist Fritz Baade, artist Rudolf Belling, numismatist Clemens Bosch, biologist Hugo Braun, botanic scientist Leo Brauner, chemist Friedrich L. Breusch, genetic scientist Ernst Wolfgang Caspari, biophysicist Friedrich Dessauer, novel writer Herbert Dieckmann, professor of German language and literature Liselotte Dieckmann, professor of law Josef Dobretsberger, linguist Wolfram Eberhard, theatre Carl Ebert, medical doctor Albert Eckstein, medical doctor Herbert Eckstein, medical doctor Erich Frank, professor of astrophysics Erwin Freundlich, artist Traugott Fuchs, archaeologist Hans Gustav Güterbock, biochemist Felix Michael Haurowitz, musician and compositor Paul Hindemith, professor of mercantile law Ernst Eduard Hirsch, architect Clemens Holzmeister, economist Alfred Isaac, sociologist Gerhard Kessler, biologist Curt Kosswig, philologist Walther Kranz, archaeologist Benno Landsberger, economist Marianne Laqueur, diplomat Kurt Laqueur, professor of medical scientist Wilhelm Liepmann, dermatologist Alfred Marchionini, professor of mathematics Richard von Mises, economist Fritz Neumark, professor of surgery Rudolf Nissen, professor of architecture Gustav Oelsner, physiologist Wilhelm Peters, professor of medical sciences Paul Pulewka, philosopher Hans Reichenbach, medical scientist Margarethe Reininger, engager of biophysical scientists Walter Reininger, mayer Ernst Reuter, businessman (general manager of Daimler-Benz AG) Edzard Reuter, pathologist Rosa Maria Rössler, economist Wilhelm Röpke, linguist Georg Rohde, economist Alexander Rüstow, archaeologist Walter Ruben, architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, medical scientist Phillipp Schwartz, medical doctor Maz Sgalitzer, novel writer Leo Spitzer, architect Bruno Taut, Turcologist Andreas Tietze, psychologist Edith Weigert, professor of law Oscar Weigert, medical doctor Carl Weisglass, physiologist Hans Wilbrandt, linguist Hans Winterstein and musicologist Eduard Zuckmayer. B. Şimşir, 2010, Türk Yahudileri Cilt ll. S. 522. lStanbul , Also see, Arnold Reisman, 2013, Turkey’s Modernization. Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk’s Vision New Academia, Washington

[xxxvii] B. Şimşir, 2010, Türk Yahudileri Cilt ll. S. 522. lStanbul

Leave a Reply