By Gökalp Erbaş

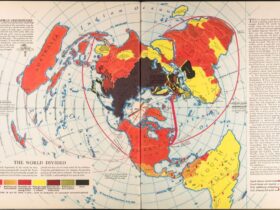

The foreign agent law, as it is known in the public opinion, appears under different names and scopes in the laws of each country where it is in force. Although it came into force in the Russian Federation in 2012 and a similar law was discussed in Ukraine in 2014, it is actually a much older law. Now, in the mainstream media, the foreign agent law is often presented as a Russian-invented dictatorial mechanism. This is very convenient both for keeping the Western examples of the law out of sight and for labelling the people responsible in the countries that are debating the foreign agent law in their parliaments as Russia’s allies.

So, what does the foreign agent law do? Although the scope, enforcement and conditions vary, countries use these laws to monitor the activities of foreign-funded organisations and individuals within the country, to ensure financial transparency, and to ensure that the foreign connections of the person or organisation concerned, as well as their political, cultural or financial goals, are known to the public. The inventor of this law is the US. In this part of our article, we will try to outline the laws of some of those countries where the law has been in force for a long time. In the second part, we will try to analyse countries where the foreign agent law / influence peddling law is relatively new or on the agenda of parliaments or the public. While analysing the laws, I have tried to make use of primary sources in particular.

First example: FARA

The USA enacted FARA (Foreign Agents Registration Act) in 1938, which we can call the ancestor of these laws. The reason for the law was the Nazi and Soviet influence in the USA. Four years before FARA, the McCormack Committee was established to oversee foreign propaganda mechanisms within the United States. In the 1960s, the USA felt the need to further develop FARA. Because, as stated by American administrators themselves, “the old foreign agents have now been replaced by professional lobbyists”. The US was aware of what this could lead to through its own foreign influence activities and wanted to protect the United States from it. Another important FARA configuration came in 2016. Rumours of Russian influence in the US Presidential elections also paved the way for the expansion of the scope of the law. Again, various additions have been made to FARA until today.

The language of FARA is quite vague, as is the case in other countries. FARA obliges organisations defined as “foreign principals”. These entities can be an NGO, a political party, a foreign government, or even a US citizen living outside the borders of the US. Individuals and organisations that operate “for or in the interests of” these foreign entities are defined as “foreign agents”. Although the law requires registration for everyone under FARA, it also includes a set of actions that it defines as “political activity”. The definition of these activities is quite broad. Political activity is defined as intending or attempting to influence “any official or agency of the Government, or any segment of the American public”.

FARA is not primarily intended to prevent the activities of foreign agents. Its main purpose is to make these individuals, organisations and activities visible and auditable by the public. Subjects under FARA are obliged to report all their activities, all income and expenditures, the amount and type of foreign funds they receive, and the purpose for which they are used to the state every six months. Subjects engaged in political activities are prohibited by law from carrying out these activities without registration.

Publications and commentators on this issue point out that although FARA is not “prohibitive”, the stigma of “foreign agent” has a negative connotation in society and often evokes “spying” activities in the intelligence sense. FARA is also particularly favourable for discrediting its Chinese and Russian-linked subjects in the American public. Vague definitions give the FARA governing body a lot of flexibility.

Funds on target: The Indian case

India was the first country to enact the law after the US. The FCRA (Foreign Contributions Regulation Act), which entered into force in 1976, underwent significant amendments in 2010 and 2020. The law differs significantly from its American equivalent. Unlike FARA, it also gives the state the power to block such activities. The Indian Government focuses on foreign funds in particular. It controls whether funds received by individuals and organisations are compatible with “the sovereignty of a free and democratic republic”. With the latest update, the government also has the legal power to prohibit “any activity prejudicial to the national interest”. The government also allows foreign funding – but only for administrative purposes – up to a maximum of 20 percent of total expenditure; it also reserves the right to ban foreign funding altogether if deemed appropriate. Unregistered organisations are prohibited from receiving foreign funding. The registration must be renewed every five years. The organisations in question must keep the funds they receive in a separate special bank account and must specify where and for what purpose every cent is to be used.

The ugly duckling: The Russian Case

The most controversial version of the law is in force in Russia. The first example in Russia was a 2006 law requiring NGOs to state the amount, source and purpose of foreign funding received. The law took a more comprehensive form in 2012. It is known as FAL (Foreign Agent Law), although this is not its official name. The law covers only non-commercial organisations engaged in political activities. Similar to FARA, the law defines political activities as activities carried out for the purpose of influencing the executive power and public opinion. The law excludes apolitical activities such as science, health services, and nature conservation. The main purpose of the law is to make organisations that carry out activities in pursuit of foreign interests explicit. Foreign agents covered by the law must comply with similar registration and reporting requirements in other countries. Government officials also have the right to conduct unscheduled inspections. The amount of foreign funding is irrelevant. Funds received in any amount still require reporting. The law aims to make foreign activities transparent in order to protect Russia’s sovereignty. However, as of 2022, there are some restrictions for subjects with the status of foreign agents. For example, such persons or organisations are prohibited from participating in state or municipal services or providing pedagogical services for minors. As in other cases, the Russian law has been criticised for “discrediting” and “stigmatising the subjects covered.

Other examples

A similar law has been in force in Israel since 2011. The law in Israel is even broad enough to cover inter-governmental organisations such as the UN, the EU and the SCO. With the 2016 update, the law includes additional requirements for organisations that receive more than fifty per cent of their donations from abroad. These organisations must display a specific sign in their activities indicating that they receive foreign funding.

The Foreign NGO Law, the Chinese version of the law, came into force in 2017. Although commercial and non-commercial organisations were regulated under an old 1984 law, this new law provides a more effective and regular regulatory oversight of NGOs. In China, it is legal for foreign NGOs to operate in areas such as economy, culture, science and health, but it is forbidden to engage in profit-making, political or religious activities. In addition, foreign NGOs cannot be established directly on Chinese territory. They must have tax-exempt NGO status in their country of origin and must have been operating for at least two years. In order to operate, a foreign NGO must be registered and receive official approval from the Professional Supervision Unit (PSU) for registration. This approval is usually assessed on a case-by-case basis rather than a general procedure. Unlike other countries, Chinese law prohibits foreign NGOs from fundraising in China. Other periodic reporting and transparency requirements are similar to other laws. The powers of the PSU are also broader in China compared to other laws. The activities of the NGO in concern can be banned in cases that may pose a threat to national security.

Although the example of the law in Germany may not be considered in the same category as other foreign agent laws, Germany also has a lobby registration law. According to the law, NGOs must register before entering into a relationship with a member of parliament or government representing foreign interests. There are no special regulations for external funding in Germany. All NGOs that receive more than twenty thousand euros in annual donations must declare their donors. If they refuse to comply with this transparency, they are registered in a separate class. Although we cannot fully include this law in the group of foreign agent laws, we can recognise it as a strong example of agency registration laws.

Common necessities for different countries

Although the social structure and the ideological and international positioning of the governments vary, the current situation shows that these governments recognise the potential of unregulated foreign NGOs to harm national interests and have taken appropriate legal actions. The dates of the enactment or significant restructuring of most laws coincide with the same periods, after 2010. Now the law is again on the world agenda and further restructuring is on the table of most parliaments. This illustrates the crucial role of civil organisations in the changing world. In the second part of the article, we will look at the examples of Türkiye, Georgia, Hungary and Slovakia to illustrate why these countries need this law and how the national and international debate on this issue is developing.

• Nägele, C. A. (2022). Non-Governmental Organizations as Foreign Agents – Foreign Funding of NGOs in Domestic and International Law [Dissertation]. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

• Frequently asked questions. (2023, April 10). https://www.justice.gov/nsd-fara/frequently-asked-questions

• FCRA Online Services. (n.d.). https://fcraonline.nic.in/home/index.aspx

• New law on activities of foreign agents. (2022, June 29). The State Duma. http://duma.gov.ru/en/news/54760/

Leave a Reply