Yes, a very significant portion of the New Testament was written in Anatolia. This is one of the fundamental truths that makes Anatolia “sacred” for early Christianity.

By Dr. Halim Gençoğlu

Pope Leo XIV’s visit to Türkiye was planned due to the 1700th anniversary of the First Council of Nicaea, which holds a very important place in Christian history. The council, which convened here in 325, is considered one of the earliest and most significant meetings in which church doctrine was shaped. This visit carries not only religious meaning but also historical and interdenominational ecumenical significance. Pope Leo XIV’s aim is to demonstrate unity, dialogue, and solidarity among different Christian denominations. The visit is the Pope’s first international trip during his papacy, and the Nicaea program stands as the focal point of this journey. Pope Leo XIV’s predecessor, Pope Francis, had previously expressed a desire to visit Nicaea, but after his passing, this visit was taken over by Pope Leo. This means that the visit is, in a sense, the fulfillment of a “testament” and the continuation of an earlier plan.

Nicaea is a center where “unity of faith and the shaping of doctrine” took place in Christian history, and the Pope’s choice to go there symbolically conveys a message of “inter-church unity and dialogue.” At the same time, this visit is seen as a step toward shaping Pope Leo’s papacy. The fact that the new Pope chose Türkiye as his first destination and visited Nicaea is viewed as both a diplomatic and religious message to the Catholic world and to Türkiye.

The Place of Anatolia in the Christian World

One must not forget that a large portion of the books of the New Testament was written on the territory of present-day Türkiye namely, Anatolia. This is no coincidence, for the geographical and theological center of early Christianity was Anatolia. Let us explain this from a theological perspective with references. Of the 27 books of the New Testament, thirteen are traditionally attributed to Paul. Most of these were addressed to churches in Anatolia and many were written there. Galatians (Konya, Ankara, Eskişehir region), Ephesians (Selçuk, İzmir), Colossians (near Denizli). Timothy served in Ephesus, and the letters were likely written in Ephesus.

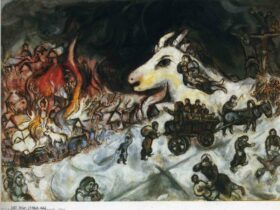

The First Letter of Peter is addressed to five Roman provinces in Anatolia (Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, Bithynia). Traditionally, it is said to have been written from “Babylon.” Early church writers like Papias or Eusebius say this “Babylon” was Rome, but some modern scholars discuss whether it symbolically referred to a central location among the Anatolian churches. Revelation was definitely written by John while he was in exile on the island of Patmos off the coast of İzmir. The first three chapters of the book directly address the seven churches in Anatolia: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea.

Thus, at least 7–8 books of the New Testament were written in Anatolia, and 15–20 were addressed to Anatolian churches. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were written mostly in the Antioch–Jerusalem–Syria–Palestine region.

In the first 150 years after the crucifixion of Jesus, Christianity experienced its fastest growth in Anatolia. Cities such as Antioch (Hatay), Ephesus, Smyrna (İzmir), Nicaea (İznik), Chalcedon (Kadıköy), and Constantinople (Istanbul) were centers of theological debates and councils. By the end of the first century and the beginning of the second, the largest Christian population in the Roman Empire lived in Anatolia.

The “Hellenization” of Christianity and the development of its philosophical language occurred largely through the influence of the Hellenistic Jewish and Greek culture of Anatolia.

Why Is the West Hostile Toward Turks?

This historical fact can be interpreted as one of the psychological and historical backgrounds of certain Islamophobic or Turkophobic narratives in the West. When the Turks arrived in Anatolia in the eleventh century, the world they encountered was not merely Byzantium, but the sacred lands of Early Christianity. In Crusader propaganda, “Holy Land” meant not only Jerusalem but also the sacred sites of Anatolia, such as Paul’s churches, the “Seven Churches,” and the House of Mary in Ephesus. After the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Western Christian world saw Anatolia as a “lost Christian homeland.” This sentiment, combined with twentieth-century nationalism, strengthened the narrative that Anatolia was originally Christian Greek/Roman territory. Even today, in certain far-right or Orthodox nationalist circles, the dream of “retaking Anatolia from the Turks” (Megali Idea, etc.) persists. This is a reflection of a historical trauma. As the late historian Halil İnalcık said: “As a historian, I warn you—The West has never given up on Hagia Sophia and Istanbul.”

Thus, the idea that “most of the New Testament was written in Anatolia, but now Turks and their Muslim civilization live there” became one of the subconscious sources of alienation and a sense of loss in the West. This feeling can easily transform into political hostility. Between the 7th and 11th centuries, with Turkish and Arab incursions, the population diminished, churches were abandoned or converted into mosques. Even though the call to prayer rises in these lands today, the stones of these seven cities still bear witness to the faith struggles of 2,000 years ago. From Osman Hamdi Bey to Ekrem Akurgal, Turkish archaeologists have meticulously uncovered these sites, and today millions of Christian tourists visit these churches to touch their roots.

“‘To the one who overcomes, I will grant to eat of the tree of life, which is in the paradise of God.’ (Revelation 2:7)”

These words seem still to echo in the wind among the ruins of Ephesus… In this sense, the proposition that Christianity is an “Anatolian religion” is largely true. The Book of Revelation was written on Patmos (Aegean Sea, administratively tied to Aydın). The lesson is that the origin of Christianity is not the “West” but the “East,” and the heart of this East is Anatolia.

Saint Nicholas—known as Santa Claus—lived in the 4th century in Myra, a city of the Lycian region, today’s Demre in Antalya. This period corresponds to the Roman and Byzantine eras, when Christianity spread early and densely in Anatolia. Thus, the tomb in Demre is a concrete indicator of the deep historical and geographical roots Christianity has in Anatolia. It also shows that the modern figure of Santa Claus originates from this Christian saint of Anatolia. Especially in the 19th century, with diplomatic relations in Europe, the protection of archaeological and religious heritage became a matter of international prestige. For this reason, structures like the Church of Saint Nicholas in Demre were restored during various periods and attracted interest from Europe.

The Europe-centered Christian narrative (Rome, Constantinople, the Vatican, etc.) developed later. The theological centers of the first three centuries were definitely in Anatolia (Ephesus, Antioch, Cappadocia, Nicaea, Chalcedon—these councils were all held in Anatolia). Therefore, Christianity is not the “religion of Europeans” but a Near Eastern religion born within the Anatolia–Palestine–Syria triangle.

The Turks are the inheritors of the land on which Christianity’s sacred texts were written. This geography is now Türkiye. This means that Turks live on land where both the most sacred texts of Islam and those of Christianity were written and where the most important churches were established. This gives Turkish society a very special historical responsibility and richness.

In the context of Christianity, the perception of it as a “foreign religion” is historically incorrect. In Türkiye, Christianity is sometimes seen as a “Greek–Armenian religion” or “the religion of the West.” Yet much of the New Testament was written on lands inhabited today by Turks, by Anatolian natives who spoke Greek. In other words, Christianity is one of the “native” religions of this land; not an incoming faith, but one that emerged from here.

How Did the Ottomans Embrace This Heritage?

It is more accurate to divide the Turkish approach to Christianity into two categories: The Ottoman Empire was a multi-religious, multi-ethnic state. For this reason, Orthodox Greeks continued to preserve figures like Saint Nicholas as part of their religious identity. The Ottomans generally did not interfere with the functioning of the Orthodox churches and even allowed them to maintain their patriarchates. Christian sacred sites were often allowed to remain in use or to be restored.

In this sense, the Ottoman Empire did not deny the Byzantine-Christian past of Anatolia but positioned it as part of the historical identity of the region within its own political order. For the Ottoman state, the ancient or Christian past of a region was accepted as part of its historical character.

In summary, Türkiye can comfortably claim to be “not only the cradle of Islamic civilization but also the cradle of Christianity.” This does not mean Christianization or abandoning Islam; it is simply an acknowledgment of historical truth. Cappadocia, Ephesus, Antioch, Tarsus, and the Seven Churches are already living evidence of this reality.

If much of the New Testament was written in Anatolia, then these lands belong not only to Muslim Turks but also to all of Christianity—granting Turkish society an extraordinary historical richness and a mission to act as a universal bridge.

This awareness opens the door not to hatred, but to a confident peace. From the Seljuks to the Ottomans and to the Republic, we are responsible for preserving this cultural heritage—just as we preserve the 1,500-year-old Hagia Sophia.

Conclusion

Yes, a very significant portion of the New Testament was written in Anatolia. This is one of the fundamental truths that makes Anatolia “sacred” for early Christianity. The Islamization of this geography after 1071 created a sense of “loss” in the Western Christian world. This perception is one of the historical-cultural foundations of modern Western hostility toward Turks and Muslims. The Ottomans, however, embraced this heritage not religiously but within a framework of administrative tolerance, cultural diversity, and political pragmatism. This shows that Anatolia is a multi-layered historical geography that does not belong to any single civilization.

Sources

F. F. Bruce, New Testament History (1983)

H. Gençoğlu, Ottoman Cultural Legacy in Southern Africa, TTK (2020)

W. M. Ramsay, The Church in the Roman Empire Before A.D. 170 (1893) and St. Paul the Traveller and Roman Citizen (1895)

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity (1996)

Adolf von Harnack, Die Mission und Ausbreitung des Christentums (1902)

Leave a Reply