A historical review.

A historical review.

By Dr. Halim Gençoğlu

American politician Malcolm X said that in 1964 “You can’t understand what’s going on in Mississippi if you don’t understand what’s going on in the Congo. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare”…

Indeed, the United States has long presented itself as the champion of democracy and human freedom, yet its policies toward Southern Africa during the Cold War and beyond reveal a far more cynical agenda: the preservation of white minority regimes, the protection of strategic mineral resources, and the ruthless containment of any revolutionary movement that threatened Western corporate interests, even when those movements were fighting the most blatant forms of racial oppression. Two emblematic episodes expose the hollowness of Washington’s moral posturing. Che Guevara’s bitter experience in the Congo in 1965 and the fact that the United States kept Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) on its terrorist watch list until 2008.

Che Guevara in the Congo

In 1965 Ernesto “Che” Guevara arrived in eastern Congo to support the Lumumbist rebellion against the U.S.-backed Mobutu regime. What he encountered was a devastating revelation about the real priorities of Washington and its allies. In his Congo diaries (later published as The African Dream), Guevara repeatedly expressed frustration and disgust at the lack of material and political support from supposedly sympathetic African states, but his sharpest criticism was reserved for the United States and its regional proxies.

The CIA had been instrumental in the 1960 assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the Congo’s democratically elected prime minister, and in installing Mobutu Sese Seko, a corrupt dictator who would plunder the country for 32 years. While Guevara and his Cuban comrades fought alongside the Simba rebels with extraordinary courage (often the only disciplined force on the battlefield), the United States poured weapons, money, and white mercenaries (including South African and Rhodesian fighters) into crushing the rebellion. Guevara wrote that the revolution was being strangled not just by local disorganization but by a concerted imperialist effort led by Washington, Brussels, and their white-ruled allies in Pretoria and Salisbury.

By November 1965, disillusioned by the lack of revolutionary consciousness and betrayed by neighboring regimes that feared U.S. pressure more than they supported pan-African solidarity, Guevara withdrew. His conclusion was brutal: the United States would rather back racist, fascist-leaning regimes across the region (Mobutu in Congo, Smith in Rhodesia, Vorster in South Africa) than tolerate even the remotest possibility of a socialist-oriented government in mineral-rich Central and Southern Africa. The Congo operation became, in Che’s own words, a “lesson in what must not be done,” but more importantly it exposed the real hierarchy of American values: strategic resources and anti-communism always outweighed any rhetorical commitment to freedom or anti-colonialism.

From Apartheid’s Best Friend to Mandela the “Terrorist”

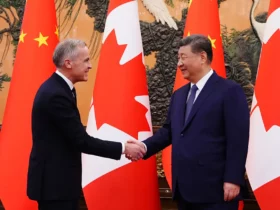

The same logic governed U.S. policy toward South Africa itself. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, while the Reagan and Bush administrations spoke of “constructive engagement” with the apartheid regime, the CIA and the Pentagon treated the ANC, the leading anti-apartheid organization, as a Soviet proxy and therefore an enemy. Nelson Mandela, imprisoned since 1962, was not simply ignored by Washington; he was actively demonized.

In 1986, Congress overrode President Reagan’s veto to impose limited sanctions on South Africa, but the administration continued to classify the ANC as a terrorist organization. Mandela himself remained on the U.S. terrorist watch list, a designation that required special State Department waivers for him to even visit the United States after his release in 1990. This absurd situation persisted for 18 years after he walked out of Victor Verster prison, 15 years after he became president of South Africa, and even five years after he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Only in July 2008, under intense pressure and with considerable embarrassment, did Congress finally pass legislation removing Mandela and the ANC from the terrorist list, a full 44 years after his conviction in the Rivonia Trial. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice famously called the lingering designation “embarrassing,” but the delay was no bureaucratic oversight. It reflected the same Cold War calculus that had led the U.S. to prop up Mobutu, arm Renamo terrorists in Mozambique, fund UNITA’s Jonas Savimbi in Angola, and veto UN resolutions condemning apartheid dozens of times.

Cobalt, Diamonds, Gold, and Geopolitical Dominance

Southern Africa sits atop some of the world’s most critical minerals: cobalt and coltan (essential for electronics and missiles), platinum, chromium, gold, diamonds, uranium. During the Cold War, the Pentagon repeatedly argued that losing access to these resources to “Marxist” governments would be catastrophic for Western defense industries. This was the real driver behind U.S. policy not human rights, not democracy, not even sincere anti-communism, but the defense of corporate access and white minority control that guaranteed it.

The same pattern continues today in subtler forms: AFRICOM’s expanding military presence, “counter-terrorism” partnerships that conveniently secure mining regions, and diplomatic pressure on governments that threaten Western mining concessions (Zimbabwe, DRC, Tanzania). The rhetoric has changed, now it is about “responsible investment” and “governance” but the underlying objective remains remarkably consistent with the era when Washington helped kill Lumumba, abandoned Che’s Congo revolutionaries, armed apartheid’s allies, and branded Nelson Mandela a terrorist until 2008.

Che Guevara left Africa convinced that genuine liberation would require confronting American imperialism head-on. History has largely vindicated his analysis. The United States did not support African freedom when it conflicted with its economic and strategic interests, and the scars of that betrayal from Kinshasa to Cape Town are still visible today.

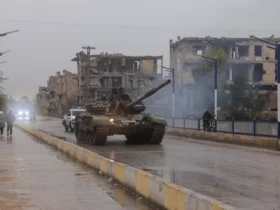

The United States’ Role in the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002)

The Angolan Civil War, one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts in post-colonial Africa (over 500,000 dead, millions displaced), was fundamentally a Cold War proxy war. The United States played a central, aggressive, and sustained role on the side of the anti-government forces (primarily UNITA and, for a shorter period, FNLA) against the Soviet- and Cuban-backed MPLA government.

Support for apartheid South Africa and keeping Nelson Mandela on the U.S. terrorist list until 2008. Arming and funding Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA in Angola (1975–2002), prolonging a civil war that killed over 500,000 people. Backing the Rwandan and Ugandan invasions of Congo in the 1990s (the Clinton administration gave a “green light” and military training, contributing to the same 5.4 million deaths). But in terms of deliberate destruction of an entire nation’s future for cold strategic gain, the overthrow of Lumumba and the decades-long sponsorship of Mobutu remain the most catastrophic and cruel American intervention in African history. The Congo has never recovered; it is still one of the poorest and most violent countries on earth sixty-five years later. The Democratic Republic of Congo alone should be one of the richest countries on earth by resource wealth; instead, it has a GDP per capita of ~$600 because of the chain of events that began with the CIA killing Lumumba in 1961. In one sentence: Washington chose oil, anti-communism, and alliance with apartheid over Angolan lives, and deliberately prolonged one of Africa’s worst tragedies.

The United States, in pursuit of Cold War victories and corporate resource access, deliberately installed or prolonged some of the most brutal regimes and wars in African history and the continent is still paying the price in blood and poverty today.

References

1. Guevara, Ernesto “Che”. The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, 2006.

3. Prashad, Vijay. The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New Press, 2007

4. Minter, William. Apartheid’s Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique. Zed Books, 1994.

5. Gleijeses, Piero. Conflicting Missions: Havana and Washington in Africa, 1959-1976. University of North Carolina Press, 2002

6. Saunders, Christopher & Southey, Nicholas. Historical Dictionary of South Africa. Scarecrow Press

7. U.S. Congress. “A Bill to Remove Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress from the Terrorism Watch Lists” (H.R. 5690), 110th Congress, 2nd Session, 2008.

8. Rice, Condoleezza. Statement on the removal of Mandela from terrorist watch list, U.S. Department of State, July 1, 2008.

https://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2008/07/106372.htm

9. Weiner, Tim. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. Doubleday, 2007

10. United Nations Security Council resolutions vetoed by the United States on apartheid-related issues (1970-1988), UN Digital Library

11. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Band 2, Part 2: “The State and Its Allies Outside the Security Forces”

12. Borstelmann, Thomas. Apartheid’s Reluctant Uncle: The United States and Southern Africa in the Early Cold War. Oxford University Press, 1993.

13. Massie, Robert Kinloch. Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years. Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1997.

Leave a Reply