Why President Boluarte was dismissed, and how the institutional context looks like.

Why President Boluarte was dismissed, and how the institutional context looks like.

By Fernando Esteche

The unexpected fall of Dina Boluarte

On October 10, 2025, the Peruvian Congress removed Dina Boluarte from office with unprecedented force: 122 votes in favor out of a possible 130, with no votes against. What had seemed unthinkable hours before was accomplished in a marathon session that ended in the early hours of the morning, marking the seventh presidential change in just nine years. The speed of the process—without any prior signs that same day—and the unanimous support of those who had kept her in power for almost three years reveal much more than a security crisis: they expose the profound nature of contemporary Peruvian politics and the concurrent crises that foreshadow a depleted system.

The formal argument for her substitution was Boluarte’s “permanent moral incapacity” in the face of the brutal escalation of citizen insecurity. The exponential growth in extortion and homicides (an average of 6.4 per day) and the establishment of power structures that have colonized Congress, the judiciary, and the government have made the situation so unsustainable, reaching the point that a renowned cumbia band was gunned down on stage during a concert.

The transportation sector is the visible trigger: nearly 50 drivers have been murdered in Lima and Callao in the last twelve months, companies have been paralyzed by threats, and a truckers’ strike blocked the capital days before the dismissal.

However, the security crisis was the pretext, not the cause. The real reason lies in a cold political calculation: Boluarte had become a toxic liability for the right-wing forces that sustained her. With a mere 3% approval rating and 93% disapproval, the president was the most unpopular leader in Latin America. Six months before the April 2026 elections, the conservative parties—Keiko Fujimori’s Popular Force, the Alliance for Progress, and Lima Mayor Rafael López Aliaga’s Popular Renewal—faced a brutal electoral reality: continuing to associate themselves with Boluarte was suicidal.

These same parties had protected her for almost three years, saving her from six previous impeachment motions. They tolerated her even during the more than 50 deaths in the 2022-2023 protests, when police repression was brutal against demonstrators demanding her resignation following the institutional coup against Pedro Castillo. They endured her through corruption scandals, from Rolex watches to accusations of illicit enrichment. But the approaching elections changed everything: calculations of power overcame any political loyalty.

The message is clear: it wasn’t moral outrage that mobilized Congress, but rather the electoral survival instinct of a political class that needs to distance itself from a failed government to maintain its grip on power.

Structures of violence, chaos and institutional colonization

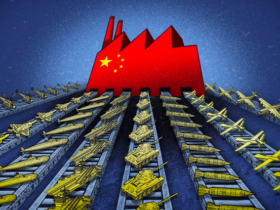

The picture becomes more complex when we look at the structural interests at play. Peru faces a crisis of institutional capture by illegal mafia economies that move approximately $10 billion annually. Illegal mining, which has surpassed drug trafficking as the main illicit activity, generated $4.6 billion in illegal gold alone during 2023, representing 44% of all national gold production.

These criminal economies do not operate in a vacuum: they require territorial control and, above all, a complicit or incapable state. The strategy is not to steal from the state through corrupt contracts (traditional corruption), but to keep it inoperative in the territories they control. To achieve this, they systematically infiltrate politics with campaign financing through front men, shell companies, fake NGOs , and cryptocurrencies; the placement of political cadres in coca, illegal gold, or timber-producing areas—it is virtually impossible for a candidate not to originate from or be supported by these economies; and control over potential regulations, conquering spaces in Congress and the Executive Branch to block oversight and informally legalize their operations.

The Peruvian Parliament represents one of the country’s biggest institutional problems, with a symbiotic relationship with the illegal mafia economies. Strategic inaction in the face of the lack of effective laws against organized crime is not just incompetence; it serves interests that require state weakness. The underfunding of the fight against organized crime is systematic; while illegal economies expand, state resources to combat them are reduced.

The dismantling of DIVIAC (High Complexity Investigation Division) when it began investigating political power is a paradigmatic example. When the State demonstrates a real capacity to combat organized crime, it is deactivated.

The police paradox: effective repression, ineffective security

One of the most revealing contradictions is the asymmetry in police effectiveness. The security forces, who were unable to prevent the murder of 50 drivers in Lima and who failed to dismantle extortion networks operating in broad daylight, demonstrated brutal effectiveness in repressing protests: more than 50 people died during the 2022-2023 demonstrations against the coup against Castillo, and one more recent death in the protests following Boluarte’s ouster.

This selectivity is no accident. The Peruvian state—or more precisely, the interests that control segments of it—prioritizes neutralizing social protest over combating organized crime. This is not incompetence but functionality; illegal mafia economies require a state that is strong against political dissent but weak against economic crime.

The growing policing of the Peruvian state is evident in the militarization of protest responses, the use of armed forces in civil demonstrations, protocols for the use of lethal weapons against unarmed protesters; the criminalization of protest, classifying roadblocks as “terrorism” and prosecuting social leaders; impunity in repression, with none of those responsible for the 50 deaths in 2022-2023 having been prosecuted; and the dismantling of anti-crime capabilities, such as the dismantling of the aforementioned DIVIAC (National Institute of Trafficking in Persons with Disabilities).

This state model serves multiple simultaneous interests. Mafia-like economies maintain territories without oversight; traditional parties avoid investigations that compromise them; external geopolitical interests, whatever they may be, prefer a weak state that cannot negotiate from a position of strength.

Presidents who defraud and right-wing continuity

Pedro Castillo’s imprisonment represents more than the incarceration of a president. It symbolizes the closing of a cycle of popular hopes that the political system could be transformed from within. Castillo, a rural teacher from Cajamarca, embodied the aspirations of “deep Peru”—that Andean, rural, impoverished country systematically excluded from the Lima elite—which for the first time in decades saw the possibility of accessing power.

Before Castillo, Ollanta Humala had raised similar expectations. With nationalist rhetoric and promises of inclusion, Humala channeled popular discontent in 2011. However, once in government, he quickly aligned himself with corporate interests and traditional elites, betraying his electoral base. Humala’s government demonstrated that even an outsider with anti-establishment rhetoric can be co-opted by existing power structures.

Castillo repeated the pattern with even greater drama. Elected with just 50.1% in a polarized runoff against Keiko Fujimori, he never managed to build governability. His government was systematically sabotaged by Congress, but he also made egregious management errors. The institutional coup of December 2022—when he attempted to dissolve Congress and was immediately arrested—abruptly ended the experiment.

Castillo’s fall represents the structural impossibility of Peru’s deep political transformation from positions of government. The implicit message is brutal: they can vote, but they cannot govern. They may win elections, but real power remains in the hands of bureaucratic elites who control Congress, the media, the judicial system, and the armed forces.

This accumulated frustration—Humala defrauding, Castillo being overthrown—fuels a corrosive political cynicism.

The inauguration of José Jerí, the Speaker of Congress, sends clear signals. At 38 years old, this lawyer from the right-wing Christian Democratic party Somos Perú promised “war on crime” and called for the cooperation of the judiciary. However, he is saddled with a complaint filed two months ago for alleged sexual assault.

Jerí represents minimal institutional continuity, but also the fragility of a political system where technical leaders lack popular support or real capacity for transformation. His term until April 2026 will likely be one of administrative transition rather than structural change. Peru will most likely continue the cycle that has characterized its politics since 2016: changes of government without structural change.

The devil sticks his tail in the popular protest

Boluarte ‘s dismissal reveal an additional and paradoxical dimension of the Peruvian crisis: the simultaneous nature of legitimate demands and mobilization patterns that replicate characteristics observable in other, more distant geographical contexts. Peruvian Generation Z has emerged, supported by major news networks, as a leading actor in these demonstrations, utilizing an iconography and repertoire of action that raises questions about the organizational autonomy of these movements.

It’s striking that the protests in Lima share symbolic elements with recent mobilizations in Nepal, Madagascar, and other seemingly unrelated geographies. The use of the skull and crossbones as a pirate flag, taken from the anime “One Punch Man,” is striking. The aesthetics of posters with similar fonts, analogously structured hashtags, and virtually identical digital mobilization techniques, speak of a learned logic.

This symbolic homogenization in such diverse contexts can hardly be explained by spontaneous convergence. The algorithms of digital platforms operate as vectors of cultural standardization, prioritizing content that has already proven viral in other contexts, but this instrumentalization speaks to a hybrid warfare combined with cognitive warfare.

Generation Z, natively digital, consumes this content without necessarily understanding its genealogy. The aesthetics of resistance become a cultural commodity that circulates globally, disconnected from the historical and cultural particularities of each territory. This doesn’t invalidate the concrete demands—insecurity in Peru is real and urgent—but it does raise questions about who defines the repertoires of action and with what strategic objectives.

There are documented indications of the presence of organizations linked to the software American power in the training ecosystem of young Latin American activists. CANVAS (Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies), a direct heir to the Otpor! movement that overthrew Slobodan Milošević in Serbia, has conducted workshops in several countries in the region. Open Society George Soros’s Foundations has funded “youth empowerment” and “citizen participation” programs in Peru for over a decade. Freedom House maintains fellowship programs for “emerging leaders” that include training in digital mobilization and nonviolent action.

These organizations don’t operate clandestinely; their activities are public and legal. The question isn’t conspiratorial but methodological: what kind of training do they offer and what conceptual frameworks do they use? This is precisely the kind of repertoires that organizations like these promote and that are known as color revolutions.

What is remarkable is that the post-Boluarte Peruvian protests have followed patterns with almost textual precision, including their timing: demonstrations that do not seek to overthrow the system but rather to force a change that keeps the power structures intact. In the Peruvian context, this does not imply that each protester is a conscious agent of the State Department, but rather something more subtle and effective: the creation of an ecosystem where certain repertoires of action are presented as “natural” or “universal,” while others—traditional union mobilization, peasant organizations, indigenous movements—are perceived as “obsolete” or “undemocratic.”

The legitimacy of protest and its instrumentalization

It is crucial not to fall into the error of delegitimizing social protest because it may be exploited by external actors. The demands of the Peruvian protesters are legitimate: insecurity is real, corruption is systemic, inequality is obscene, and the economic future of young people is precarious. These objective conditions are sufficient to generate mass mobilization without the need for external engineering.

However, there is no contradiction between recognizing the legitimacy of demands and critically analyzing their repertoires, timing, and potential instrumentalizations. A movement can have justified reasons and simultaneously be channeled toward objectives that do not respond to the interests of its participants.

The soft Power operates precisely in this gray area: it doesn’t create discontent—which is genuine—but rather channels it, shapes it, provides it with repertoires of action, defines strategic enemies, and orients its results toward changes that don’t alter fundamental power structures. In the Peruvian case, Boluarte’s fall does not represent any structural change. José Jerí, her successor, is part of the same political establishment that sustained him for three years.

The strategic question is: who benefits from the fact that legitimate protest does not result in structural transformation but merely in the replacement of figures? The answer includes both the domestic elites who maintain control of the hijacked state and external geopolitical actors who prefer a weak and unstable Peru to one capable of sovereignly negotiating its integration into global production chains.

The geopolitical dispute over Peru

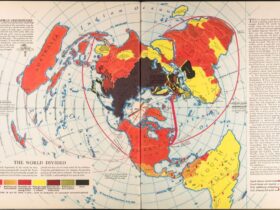

Peru has become a point of contention between the United States and China at a time of restructuring the international order. Chinese megaprojects—the Port of Chancay and the future Bioceanic Railway—are not mere commercial investments but rather pieces of a long-term strategy to reshape global trade flows.

For the United States, Chinese consolidation in Peru represents a multiple strategic threat: control of critical infrastructure—China handles 100% of the energy in Lima and almost 70% nationwide, in addition to the port of Chancay; access to strategic resources—Peru is rich in lithium, copper, and rare earths, all of which are essential for the global energy transition; logistics platform—Chancay and the bioceanic railway would turn Peru into a hub connecting the Brazilian Atlantic with the Pacific, bypassing the US-controlled Panama Canal; and regional precedent—if China consolidates its presence in Peru, other Andean countries could follow suit.

In this context, Peru’s political instability is not necessarily a problem for Washington but potentially a tool. A weak government, beset by protests and surviving crisis after crisis, lacks the capacity to negotiate from a position of strength with Beijing. The alternative—a strong nationalist government that negotiates sovereignly with both powers—would be less manageable for US interests.

The U.S. Embassy in Lima and Southern Command maintain deep ties with Peruvian military, police, and intelligence sectors. These ties, built over decades of “counternarcotics cooperation,” provide channels of influence that don’t require visible intervention. A leaked report, a timely journalistic investigation, funding for specific NGOs, scholarships for emerging leaders: these are the tools of soft power, more effective than any military coup because they are invisible and deniable.

Between the Scylla of mafia capture and the Charybdis of geopolitical instrumentalization

Peru faces a strategic trap: its state is simultaneously being captured by mafia-like criminal economies and contested by global powers, while its legitimately indignant population protests in the streets using repertoires that may be being exploited.

The way out of this trap would require rebuilding state capacity—a state that can effectively combat organized crime without repressing legitimate social protest; strategic sovereignty—the ability to negotiate with China and the United States from positions of strength, not weakness; profound political reform—institutions that genuinely represent the Peruvian heartland without being captured by illegal economies or corrupt elites; and the autonomy of social movements—grassroots organizations capable of defining their own repertoires of action without depending on transnational NGOs with their own agendas.

However, given the current configuration of forces—corrupt elites, infiltrated organized crime, external geopolitical pressures, and social movements lacking strategic coordination—it is difficult to foresee how this alternative project might emerge. The April 2026 elections will likely produce another weak government, incapable of addressing structural crises, doomed to repeat the cycle of institutional decline that has characterized Peru for a decade.

The security crisis is real and urgent, but it is also a symptom of a deeper malaise: the loss of the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence, the colonization of entire territories by criminal economies, and the inability of traditional politics to represent and defend the national interest in the face of illicit private interests and external pressures.

The April 2026 elections will not just be an electoral contest; they will be a battle to determine whether Peru can regain its viability as a nation-state capable of governing its territory and negotiating its integration into global chains, or whether it will continue its drift toward a model of criminal feudalism with a democratic facade, transformed into a logistics platform for trade flows that transit untransformed, while its population remains trapped between criminal extortion and state ineffectiveness.

The devil, as the analysis of the popular protest suggests, is indeed involved: not to deny the legitimacy of the demands but to distort their results, to channel transformative energies into cosmetic changes, so that everything changes without anything actually changing. Given the current political landscape, one cannot harbor optimism about the direction this nation is taking.

Leave a Reply