The most crucial innovations will be those which enhance ecosystems, livelihoods, and peoples on the gray fringes of urban life.

The most crucial innovations will be those which enhance ecosystems, livelihoods, and peoples on the gray fringes of urban life.

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

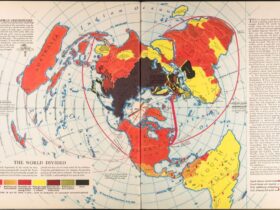

Southeast Asian urbanization is a demographic tendency—it is additionally a political, economic, and ecological milestone. As urban masses swell with countryside-to-city migration, increased incomes, and urban infrastructure expansion, the region grapples with a query squarely at the hub of sustainable growth: can ASEAN urbanize without eroding its ecological carrying capacity? The answer, increasingly, is located in the type of innovation cities employ to hold growth. Not all innovation is equal, however—and the dynamic between native-born innovation and outside technology is shaping up as one of the most defining and delicate in the city transformation.

Across ASEAN, the green cost of swift urbanization is becoming more apparent. Jakarta’s air pollution, Ho Chi Minh City’s flood, Manila’s water shortage, and Bangkok’s heat are not independent crises—each is a symptom of an ecological system experiencing persistent stress. Ecological footprints of urban areas are growing disproportionately because they use more energy, waste, alter land, and use unsustainable transport. The rising environmental impact of Southeast Asian urban agglomerations now threatens biodiversity, dismantles rural-urban resource flows, and exacerbates the very climate risks that urbanization was conceived to mitigate through density and efficiency.

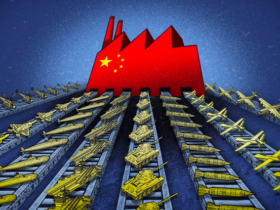

But though the environmental pathology diagnoses are already familiar, remedies remain contentious. Governments, donors, and private firms have encouraged a whole range of technological and policy innovations—from green building codes to smart city initiatives, electric vehicle fleets, and climate-resilient infrastructure. They are predominantly foreign, originating from Japan, South Korea, China, and Western donors. Foreign technologies are capital-intensive, high-tech, and part of international supply chains. They bring system-level transformation, improved data management, and long-term climatic resilience. And yet their actual performance is always behind their marketing hype.

The majority of imported urban sustainability technologies are poorly attuned to the sociocultural and infrastructural realities of ASEAN cities. Smart waste collection systems assume digital literacy and municipal coordination that remains patchy. Climate-resilient drainage designs assume land-use control that is lacking in most peri-urban areas. Even the shift to electric automobiles—a green modernity badge—lurks behind unstable electricity grids, low-level integration with mass transit, and prices well beyond the reach of city poor. Indigenous innovations—improved locally or fashioned by practice-led community—evince a more grounded, if less visible, form of ecological resilience.

In Indonesia’s flood-risk kampungs, for instance, bamboo building and local water harvesting systems are low-technology but resilient adjustments to climate extremes. In Vietnam’s delta regions, traditional aquaculture and floating gardens provide the city fringes a capacity to buffer ecological shocks at minimal capital expense. These forms are embedded in local systems of knowledge, environmental awareness, and cultural memory. They may not possess the overseas investment or status of their global counterparts, but they are environmentally friendly, attentive, and in their effects more inclusive. The problem isn’t that foreign innovations don’t work—it’s that they are dropped in far too often without roots. Local solutions aren’t inherently superior—but they are consistently underinvested in, underfinanced, and excluded from formal urban planning. The discrepancy between these two flows of innovation is a manifestation of broader divergences in how development is imagined and rolled out across ASEAN.

Urban planners are stuck

Foreign technologies bring scale, speed, and access to world finance. It is simpler for donors and investors to fund large-scale smart grid rollouts than bottom-up restoration of the ecosystem. These technologies, nevertheless, have a proclivity to erode indigenous involvement and consolidate centralization. Indigenous innovations are difficult to scale, difficult to standardize, and operate beyond formal economic metrics. But they are likely to be more trust-inducing, behavior-changing, and attuned to the socio-environmental fabric of Southeast Asian urban existence. It is also compounded by politics of legitimacy and knowledge. Foreign technical advisers are better remunerated and influential than local community leaders or NGOs. Urban planning initiatives all around ASEAN continue to prioritize Western models of development at the expense of environmental heritage. This provides a policy culture wherein foreign-sourced innovation is synonymous with modernity and science and local knowledge synonymous with folkloric or old-fashioned.

But for ASEAN cities to be environmentally sustainable, this pyramid must be reversed

The future of Southeast Asia’s urban environment rests on the ability to hybridize—integrating high-tech effectiveness with indigenous know-how. This means integrating indigenous water management into climate-resilient infrastructure design. It means taking green building codes to recognize not only imported certification, but vernacular architectural methods that regulate temperature and air currents without mechanical intervention. It entails building transport systems that are not only electric, but also pedestrian-friendly, green, and attuned to the mobility needs of the informal sector. Some cities are already charting this future course. In Chiang Mai, urban agriculture initiatives are combining digital monitoring systems with traditional irrigation systems. In Manila, disaster risk reduction efforts are combining satellite data and barangay-level intelligence into early flood warning systems. These are preliminary but significant signs of a new paradigm—one that need not choose between the local and the global but combines them into an ecologically rational whole.

Urbanization is not destiny

It is a choice, made time and again, through zoning, infrastructure investment, and planning philosophies. ASEAN can continue to make the choice to prioritize environmental devastation as the bitter price of progress, balancing imprints with smooth green megaprojects that never trickle down into the life of the urban poor. Or it will recognize that sustainable development is not a technical problem, but a learning, governmental, and cultural harmony issue. Perhaps the most crucial innovations will be not those which illuminate city center screens, but those which enhance ecosystems, livelihoods, and peoples on the gray fringes of urban life. That is where sustainability begins—not in unfamiliar systems, but in relearnt origins.

Leave a Reply