The future depends on commitments.

The future depends on commitments.

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

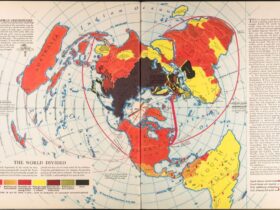

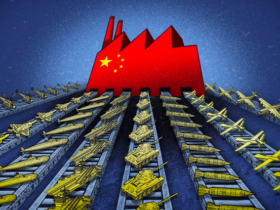

Southeast Asia stands at the intersection of two compelling forces: the world’s rapidly accelerating demand for strategic minerals and increasingly integrated regional economies through trade agreements. Bauxite and nickel, copper and rare earth elements – ASEAN’s mineral resources are more strategically valuable than ever before. As the world shifts to low-carbon technologies—electric vehicles, solar panels, battery storage, and green infrastructure—the minerals beneath ASEAN ground are being reconfigured not as extractive curses, but as geopolitical assets. And driving this new dynamic is a less visible but no less vital mechanism: regional trade agreements.

Trade agreements have long been touted as tools of tariff elimination, market access, and investment liberalization. But in mineral resource development, particularly in ASEAN, they are now acting as templates that prescribe how, where, and on what conditions mining and processing investments are made. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand Free Trade Area (AANZFTA), and the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) are not merely trade agreements—they are institutions of rule-making for the new mineral economy.

What these agreements do is bring certainty to investment environments across ASEAN. For investors looking to invest funds in long-term, capital-intensive mining projects, legal certainty and protection against arbitrary regulation are near the top of the list. RCEP, for instance, offers investment guarantees and dispute settlement mechanisms that reduce sovereign risk and allow firms to plan decades in advance, not quarters. This is particularly important in frontier economies such as Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia, where local governance institutions remain nascent. Combined with the second layer of protection through the law under trade agreements, Japanese, South Korean, and Australian investors are poised to make smart investments in ASEAN’s untapped mining sector.

No less important is how trade agreements generate infrastructure and logistics incentives. The minerals sector has an obvious dependence on processing plants, rail, roads, and ports. With programs such as the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC) and through China’s Belt and Road-related cooperation under ACFTA, cross-border infrastructure projects are all the rage. Mineral deposits are no longer conceived in discrete national border compartments, but as belonging to an integrated regional value chain. Thus, for example, Indonesia’s nickel is increasingly being linked with Malaysian downstream processing and Thai battery manufacturing, supported by partially harmonized rules of origin and lowered intra-ASEAN trade barriers. Moreover, trade agreements are reconfiguring ASEAN’s position in the global mineral value chains.

Previously, many of the Southeast Asian countries were stuck as raw material exporters, shipping to China or Japan the unprocessed ore and returning with finished goods at a premium. But trade deals are now making it easier to try to move up the value chain. As capital equipment tariffs are lowered, joint ventures with foreign firms, and special economic zones for mineral processing are created, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines are actively seeking investment in refining and value-added production. RCEP and AANZFTA provisions for technology transfer and services liberalization are key to this transition, allowing ASEAN to transition from a resource supplier to a manufacturing and export base for key minerals. Trade agreements, however, do more than bring in capital—they shape policy behavior.

Obligations under regional trade pacts have a way of demanding regulatory convergence and domestic adaptation. This is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, ASEAN governments are compelled to put in place more transparent, investor-friendly mining codes, elevate environmental standards, and ease licensing. Others, however, warn that regulatory convergence under free trade agreements can shrink policy space for the sovereign state, especially where disputes are settled by arbitration tribunals outside national jurisdiction. The challenge is to shape agreements that are conducive to investment without undermining space to regulate in the public interest, and more specifically in relation to environmental protection and Indigenous land rights. Environmental, social governance (ESG) standards are ever more the decisive factor in this calculus.

International investors and consumers are on the hook to make mineral production sustainable. ASEAN governments are beginning to mainstream ESG into investment and trade policy—whether through Philippine mining sustainable codes, Thai green infrastructure law, or Indonesian carbon-trailing export incentives currently under discussion. Trade agreements can be used to drive this process further by incorporating provisions on sustainability, making tariff preference dependent on compliance with environmental standards, and encouraging regional certification for “green minerals.” Nevertheless, there is a risk of some of the smaller or less developed ASEAN members being left behind.

Trade liberalization would be appropriate for economies with the capacity to absorb investment, provide infrastructure, and enforce contracts. In the absence of the regional institutions to redistribute the benefits, nations like Myanmar or Cambodia could just remain raw material frontiers with few benefits to citizens. It underscores the need for cooperation at the ASEAN level—not just at the level of signing agreements, but in terms of shaping how mineral investment is harnessed to advance broader development agendas. Regional development finance, mining governance capacity building, and benefit sharing mechanisms are all tools ASEAN might consider deploying across its trade system. As mineral mania deepens—fueled by decarbonization, electrification, and geopolitical insurance—ASEAN stands at the crossroads.

Its trade agreements are no longer silent documents limited to tariff schedules; they are maps to an energy-demanding future. Whether that future will be one of inclusive prosperity, environmental sustainability, and regional coherence—or one of resource dependence, environmental unsustainability, and fragmented development—will hinge not just on what ASEAN commits to do, but how it commits. The foundations are being laid today, and choices made today will determine if Southeast Asia merely powers the world’s energy transition—or contributes to defining it.

Leave a Reply