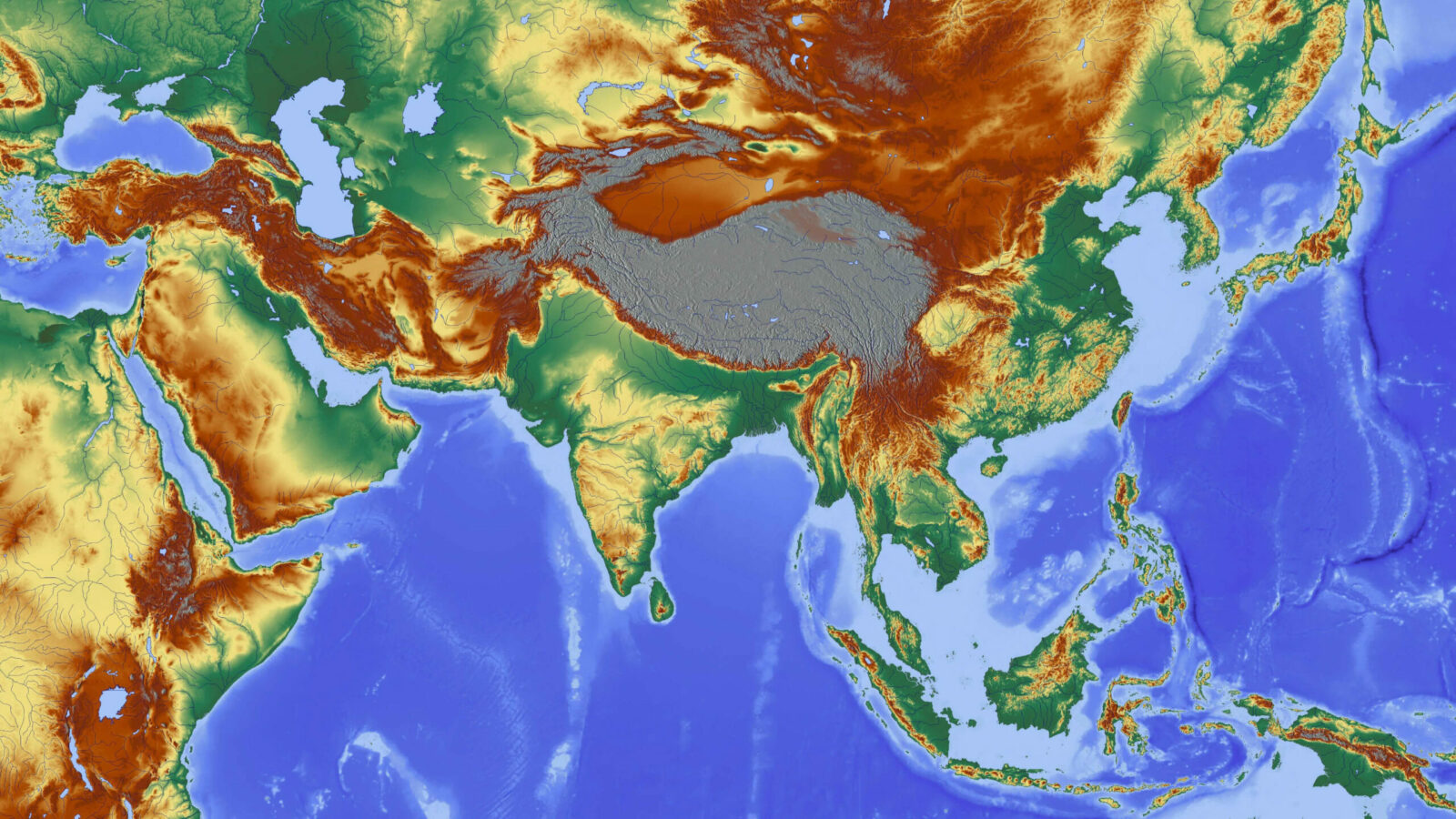

From Pakistan over Nepal to Indonesia…

From Pakistan over Nepal to Indonesia…

This year, 2025, saw the United States escalate its actions in Asia to unprecedented levels. In April, India and Pakistan continued their long history of conflict following the attack by the Resistance Front (TRF), an offshoot of the Pakistani terrorist group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, in Kashmir, which left 26 Indian tourists and a local worker dead and more than 20 injured.

In response, India accused Pakistan of supporting cross-border terrorism by expelling Pakistani diplomats and recalling its own diplomats from Islamabad. Visa issuance was suspended, borders were closed, and New Delhi withdrew from the Indus Waters Treaty . Pakistan denied the accusations and responded with trade restrictions, closure of airspace and border crossings, and the suspension of the peace treaty signed between the two countries on July 2, 1972, known as the Shimla Agreement.

Between 24 and 29 April, the Indian and Pakistani armies engaged in skirmishes and exchanged small arms fire, but on 6 May 2025, India launched Operation Sindoor, which involved missile strikes against Pakistan , targeting what it termed “terrorist infrastructure” in Pakistani Kashmir.

An agreement was reached on May 10, ending the fighting. However, both countries maintain tension-causing measures, such as the suspension of trade agreements and bilateral treaties. Both countries claimed victory, but while Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif thanked the United States for its “proactive role” in negotiating the agreement, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made it clear to US President Donald Trump that the ceasefire was achieved through talks between the two militaries and not through US mediation, as the US president had shamelessly announced to the world.

Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri was emphatic in a press release: “Prime Minister Modi clearly told President Trump that during this period, there were no discussions at any point on issues such as the India-US trade agreement or the US mediation between India and Pakistan.” This, coupled with pressure from Washington for New Delhi to stop buying oil from Russia, has strained bilateral relations and distanced two countries that have once been solid allies.

It is worth noting that in March, Pakistan announced the purchase of a stake in the New Development Bank (NDB), the financial institution of the BRICS group. It has also expressed its willingness to join this conglomerate. Similarly, it has been a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) since 2017. India, for its part, is a founding member of BRICS and has also participated in the SCO since 2017.

More recently, fighting erupted on the Thai-Cambodian border in July of this year, marking the most serious clash between the two countries in more than a decade. The violence has reignited a long-standing territorial dispute and tested ASEAN’s ability to manage sudden security crises with direct economic consequences.

The conflict has its roots in colonial-era demarcations and the disputed sovereignty of the Preah Vihear Temple. Although the International Court of Justice ruled in favor of Cambodia in 1962 and reaffirmed the decision in 2013, ambiguities over adjacent lands continue to generate tension.

The Association of Southeast Asian States (ASEAN) played a pivotal role in helping to stem this border conflict, but its hands were largely tied, as the underlying causes of the conflict are rooted in the internal dynamics of both sides.

Although it may seem that both China and the United States intervened to calm tensions, the truth is that both countries in conflict are active members of the Silk Road. Moreover, since 2014, Thailand has shown a closer relationship with China, which has made significant investments in the country. It is worth noting that Thailand joined the BRICS bloc as a Partner Country starting January 1, 2025, after accepting an invitation from Russia, then the group’s pro tempore president.

Cambodia, for its part, has been a traditional and long-standing ally of China. Its ties have strengthened since 2010, when Beijing built a deepwater seaport along 90 km of coastline in the Gulf of Thailand, accessible to cruise ships, bulk carriers, and warships.

Cambodia’s diplomatic support for China has been invaluable in Beijing’s efforts to reclaim disputed areas in the South China Sea. As a staunch ally of China, Cambodia acts as a counterweight to Southeast Asian nations that maintain closer ties with the United States.

Further west, on the borders between Asia and Europe, but also along the Silk Road route, a peace agreement was signed between Armenia and Azerbaijan on 8 August 2025 to end the 37-year-old Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The agreement included provisions for border delimitation, security cooperation, and measures to normalize relations between the two countries.

So far, everything seems normal and positive for achieving peace in this highly conflict-ridden region of the South Caucasus. But in parallel with this agreement, the United States government affirmed that Armenia would grant it exclusive rights for 99 years to develop the Zangezur Corridor, renamed the Trump Route to International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP), with the goal of connecting the now enclave of Nakhichevan with the rest of Azerbaijan through Armenia, bypassing Armenian checkpoints. This corridor would allow the transit of people and goods from Europe to Azerbaijan and the rest of Central Asia without having to go through Russia or Iran. This agreement could be considered the most important—and perhaps the only—achievement achieved by American diplomacy, and a blow to the interests of both Russia and Iran.

Indonesia on August 25th as a result of broader social unrest that began in early 2025 due to the country’s general economic situation and the proposed increase in housing subsidies for parliamentarians. The protests, which were mainly concentrated around the capital, Jakarta, intensified and spread throughout the country.

The end of the protests that prevented President Prabowo Subianto from attending the SCO Summit in Tianjin, China, earlier this month does not mean the end of the conflict. In Indonesian history, social and political processes (including the most important one that led to the end of Haji Suharto’s dictatorship in 1998) arise from the accumulation of forces and experiences that lead to higher stages of struggle.

But on the geopolitical level, it is important to note that Indonesia formally joined the BRICS bloc of emerging countries on January 7 of this year as a full member, becoming the tenth member and the first from Southeast Asia to join the group.

Finally, it is necessary to mention Nepal, the second-poorest country in South Asia after Afghanistan. It is a new republic that only achieved this status in 2008 after a decade of civil war led by a military force calling itself “Maoist” that claimed the lives of more than 17,000 people. However, the country has not achieved the desired economic and political stability. Power has been distributed between the Communist Party and the Nepali Congress, which have squandered the political capital acquired in the struggle against the monarchy. This was at the root of the protests that began on September 8 and led to the resignation of Prime Minister Sharma Oli, at a cost of more than 50 deaths, almost all of them young people, and financial losses that could amount to some $21.3 billion, almost half of the country’s GDP.

According to Hong Kong-based Sri Lankan journalist and writer Nury Vittachi, the United States recently spent more than $1 million training journalists to accuse the government of corruption, as well as training young people from the so-called Generation Z in political activism. All of this is in response to the government’s decision to express its desire to establish an independent internet model, similar to what China has done.

The instability in Nepal is having a negative impact on its powerful neighbors, China and India. At first glance, India is the big winner, given that the interim prime minister, Sushila Karki, appointed after Oli’s resignation, belongs to the elite trained in India. Furthermore, two of the three interim ministers chosen to govern Nepal until the elections are close to Indian interests. On the contrary, China, which strengthened relations with the new Himalayan republic after the end of the monarchy and recently signed important cooperation agreements with Prime Minister Oli, has seen its influence in the neighboring country diminished. One of the institutions burned by the protesters’ fury was the headquarters of the New Silk Road in Kathmandu.

For its part, the U.S. Embassy expressed its satisfaction with Nepal’s political turnaround, although it hopes to be even more so following the elections scheduled for six months from now.

Beyond the fact that some of these protests have their origin in just demands of the social movement against the economic crisis, corruption and nepotism, it is necessary to warn that although not all of them have their origin in the destabilizing will of the United States and Europe in the region, it is evident that the West is watching the events in order to get into the hearts and minds of these people to guide them towards geopolitical objectives that have nothing to do with the popular demands.

Any person of good will has the right to assume that all these facts are coincidental and that it is not valid to link them as part of an unbalancing imperial action, but as a popular saying attributed to Miguel de Cervantes says: “Witches do not exist, but they fly… they fly.”

Leave a Reply