Global decarbonization, industrial resilience, and consumer access hang in the balance.

Global decarbonization, industrial resilience, and consumer access hang in the balance.

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

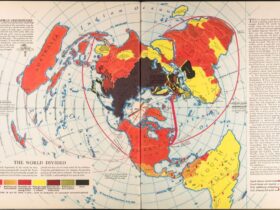

As electric vehicles (EVs) make their way from the fringes to the mainstream of the mobility revolution, a tectonic shift is happening—both in terms of technology and geopolitics. Few issues capture this shift as colorfully as the escalating trade tension between China and the European Union surrounding EVs. What initially began as a policy response to industrial competition has now evolved into a deeper debate over the future of globalization, green technology, and the essence of fair competition.

Europe’s anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric cars, and the looming spectre of retaliatory tariffs, represent a troubling turn towards protectionism. At a time when cooperation between the two is so urgently needed to support the green transformation, the present standoff risks devastating one of the foundations of international climate ambition and pushing the two countries towards industrial isolation.

The concerns of the EU are not baseless—Europe’s automotive industry is a core part of its identity and employment structure—but its present trajectory misdiagnoses Chinese drivers of competitiveness and risks sacrificing long-term interest for short-term political optics.

Misdiagnosing the Problem: The Myth of ‘Overcapacity’

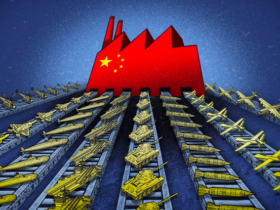

One of the principal justifications for Europe’s assertive turn has been that China’s EV sector is overproducing and “dumping” spare capacity on European markets. However, such an assertion does not stand up. Only 4.5% of Chinese new energy vehicle (NEV) production found its way to the EU in 2023, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. Moreover, China’s indigenous EV market is far from saturated—with more than 30% of the market penetrated, there is vast room for local growth.

This proof refutes the theory that China is exporting unmarketable overcapacity to other nations. Chinese EV exports to Europe are actually driven by structural benefits in battery technology, supply chain integration, and economies of scale, not overcapacity. These are not artificially produced by state subsidy alone.

Subsidies: Not a One-Sided Story

Brussels critics argue that China’s EV boom is artificially created by the aggressive government support. Granted, Beijing was an early and instrumental player in creating the EV industry—via subsidies, infrastructure investment, and research incentives. It is not correct, however, to single out China. The EU and U.S. also provided generous subsidies, spearheaded by green industrial policies like the European Green Deal and the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act.

The real difference lies not in the occurrence of subsidies, but in the application and ecosystem that they create. China’s ability to translate policy rapidly into industrial response, coupled with hyper-competition for local brands, has created a market-led, robust EV industry. Tesla, BMW, and Renault have each chosen to make or grow in China for a reason—it is not because they have been allowed to cheat unfairly, but because of scale, efficiency, and innovation.

Strategic Industry, Not Nationalism

The anxiety in Europe is not economic—it’s existential. The automotive industry has been the hallmark of European greatness for decades. German, French, and Italian brands have represented what it means to drive stylishly and comfortably. The sudden rise to prominence of Chinese EVs, especially in price-sensitive markets, is a psychic wound as much as a business obstacle.

But the answer isn’t building walls. Tariffs won’t magically restore Europe’s comparative advantage. Though they’ll temporarily slow Chinese imports, they’ll also raise prices on consumers, stifle EV adoption, and spur Chinese counter-retaliation—maybe against European luxury products and Chinese green tech.

Instead, Europe must gamble larger on its own capabilities: design, security, brand awareness, and regulatory competences. Competitive sectors must be protected not by shielding, but by bets on competitiveness—education of the workforce, R&D development, and scaling up battery production.

From Competition to Collaboration

The irony is that both China and the EU share a common interest: the decarbonization of transport. The magnitude of climate change calls for partnership, not competition. Europe cannot meet its ambition of leading the world green transition on its own. Neither can China become climate neutral without engaging with mature markets like the EU.

Instead of diving into an industrial trade war, the two sides need to consider structures for formal debate on subsidies, environmental protection norms, and intellectual property. A standing EU-China Industrial Policy Forum can help in intermediation and discover areas of co-investment, from charging infrastructure to green hydrogen.

Second, cooperation in third markets—above all, in Africa and Southeast Asia—would yield mutually beneficial outcomes. Cooperation on EV charging infrastructure, smart grid technology, and clean logistics would establish sustainable development opportunities while reducing irritation at home.

Conclusion: Saving the Future, Not the Past

Europe’s motor industry stands at a crossroads. It can attempt to preserve its legacy by imposing temporary barriers, or it can grab the future by accepting the challenge of global competition. China’s EV dominance is no illusion, merely disruption. The appropriate response is not pullback, but reinvention.

Rather than spinning wheels in cycles of protectionism, Europe and China need to push toward shared opportunity. The future is electric—and whether one of division or of co-operation depends on the politics of the day.

Global decarbonization, industrial resilience, and consumer access hang in the balance. It is not too late yet to shift gears, but only if the two sides choose dialogue over dogma, and strategy over passion.

Leave a Reply