Why the Bandung Conference was a turning point.

Why the Bandung Conference was a turning point.

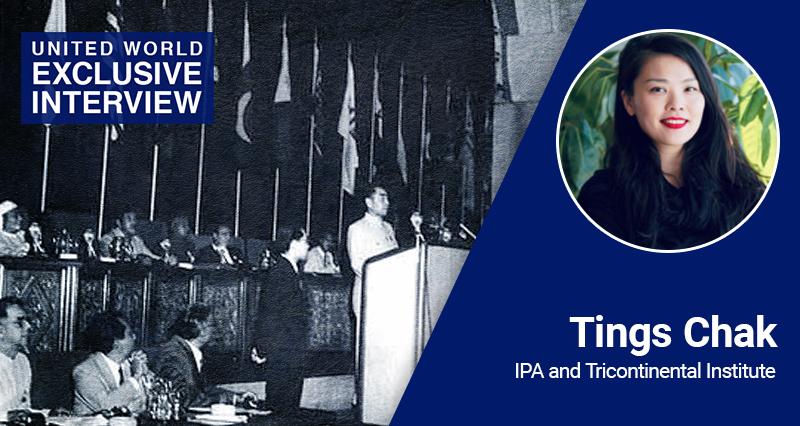

Multipolarity appears to be a contemporary concept of struggle. But Tings Chak begs to ffer. According to her, the struggle against unipolarity is as old as the struggle against colonialism, and she emphasizes the Bandung Conference as a major turning point.

Here’s what Tings Chak, who is Asia Coordinator at the Tricontinental Institute, told us.

You make a point about the history of the struggle for multipolarity. Can you explain that very briefly?

Yes, I think the struggle for multipolarity is not just a part of this current political conjuncture, not even the time since the fall of the Soviet Union, with this so-called unipolar world that emerged. Rather, it emerges out of the struggle of national liberation of Third World countries, struggling to become independent, struggling to have the right to self-determination, to have economic, political sovereignty. And this new world order is something that we have been fighting for, for the last century.

At what time would you locate this struggle? The beginning of the struggle for multipolarity? To give a date or events.

I wouldn’t want to periodize it, but since this year is a very important anniversary, the 70th anniversary of the Bandung Conference that united 29 newly or nearly independent countries across Africa and Asia as the first time to assert that we, representing half the world’s population, were standing on our own feet and also have a say in how the world is structured politically, economically, as well as self-determinations for all of our peoples and nations that were just emerging into the world stage.

So it will be the Bandung Conference?

I would call it Bandung as one of the starting moments, but of course Bandung Conference was also an accumulation of many anti-colonial struggles from Pan-Africanist movements to anti-war movements across Asia, Africa, of course later Latin America as well. Movements across Asia, Africa, of course later Latin America as well.

70 years ago, this year in a city named Bandung in Indonesia, when 29 newly or nearly independent Asian and African countries inaugurated this Bandung conference. And the leaders met with the teeming masses, walked along this Africa-Asia Road to the conference center in the building named Freedom Building. And these leaders represented the collective standing up of third world nations that had risen out of this history of brutality and colonial domination. And at the time, it represented about half of the world’s population. It was the first time on the territories of the Third World where we were claiming our nation’s right to exist, our nation’s right to self-determination, and for peaceful coexistence. I think words that are still very important for our conference and forum right now, but of course, what do we think about the so-called Bandung spirit today as we are trying to struggle for a multipolar world? We know that the Global South, what we call the Global South today, isn’t just one thing. And what we imagine this multipolar world is also not one thing. And similarly, during the Bandung period, what these leaders and countries were marching forward towards was also not one thing. And I think there’s something we can learn from that history, in particular around the capacity to unite across diversity. I think it’s that Bandung spirit that has taught us that unity across diversity is still possible.

As the host, Indonesian President Sukarno, opened the conference, and he said, and I quote, colonialism is not dead. And he noted that different forms, modern forms, through economic, intellectual, or physical control by foreign powers, and that these diverse nations united in a rather common opposition to colonialism and neocolonialism and what he called the lifeline of imperialism. He also said that we, as nations of the global south, still know very little about each other and our struggles, and I think that’s something relevant today. And at the time, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, representing the newly formed People’s Republic of China, played a really important role. And he promoted this principle called seeking common ground while reserving differences. So seeking common ground being the main principal objective.

How did the Us react back then?

So interestingly then, the US Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, explicitly feared that China’s presence would be an opportunity to spread, and I quote, communism among the naive anti -colonial nations. So Western powers violently countered Bandung’s ideal, and we saw it with decades of covert and overt operations and coups across the Third World, but the Bandung spirit still persisted in the political imagination of the Global South.

So 70 years on, this new world order, what we’ve been calling at the Tri-Continental Institute as a new mood, is emerging, it’s slowly emerging, and I think it’s aspiring towards some of Bandung’s core ideas that I already mentioned before. And this new mood is backed by material changes. We’ve seen the center of gravity of the world’s economy shift eastward, with China but also other Asian countries becoming the engines of global growth. We’ve seen institutions like BRICS, which with its continual expansion now represents nearly half of the world’s population and a third of the global economy. Furthermore, we are seeing initiatives led by China like the Belt and Road Initiative, which has mobilized 1 .17 trillion dollars in a decade not to finance war and destruction, but to build connectivity and much -needed infrastructure across 145 countries, and providing a possible alternative to this Western -centric system of the IMF, the World Bank, which we know have done nothing but to impoverish in debt and further place our countries into submission. But we know this multipolar vision faces significant resistance. Notably, of course, under the United States with Trump’s administration, which has escalated its trade war through aggressive tariff policies imposed both on friends and foes. And in a strong-arming fashion, he has announced a series of these so -called retaliatory tariffs while, of course, doubling down on China.

And we’re seeing while the US no longer has any carrots to offer, it is increasingly wielding its stick to impose its order or maintain what’s left of its hegemony. And we’ve seen this, of course, with its criminal attack on Iran and taking the world to the brink of World War III. Indeed, much like Dulles in 1955, the U.S. establishment fears the emergence of a China, perhaps then that served as an ideological threat for being the largest Communist Third World Nation, today it is seen as an economic and existential threat.

The fact that China is standing up to the US.’s bullying tactics and defending its national sovereignty isn’t just about defending China’s sovereign path. It’s also a defense of a possibility for the global South and a defense of the possibility of a multipolar world. But does this mean that the Bandung spirit is still alive today? How can we recuperate this Bandung spirit? And this contemporary rise of the Global South, though economically and politically significant, still lacks the mass-driven, anti-imperialist solidarity that marked the Bandung moment.

How do you see the role of BRICS today in that context?

Initiatives like BRICS still largely remain at the level of states and lacks extensive popular mobilization that defined the earlier era of national liberation struggles. So ultimately, in order to transform these existing multipolar trends, we are seeing emerge and to transform that into a Bandung-inspired global movement requires sustained efforts. Not only at the level of states and leaders, but through grassroots movements, people’s struggles, and the revival of a culture of solidarity and unity across diversity among peoples of the world. And Tri-Continental Institute for Social Research was founded in 2018 as a pillar of the International People’s Assembly to produce knowledge alongside these people’s struggles around the world. And now we have over 200 mass -based political organizations from around the world with the aim of building this anti-imperialist agenda and an action and revive this anti-imperialist, internationalist, and yes, Bandung spirit. And I’ll just wrap up here with a quote that I really love from President Sukarno.

He said, if the bantang, or the bull, of Indonesia can work together with the sphinx of Egypt, with the Nandi ox of the country of India, with the dragon of the country of China, with the champions of independence of other countries. If the Bantam of Indonesia can work together with all the enemies of international capitalism and imperialism around the world, oh surely end of international imperialism is coming fairly soon. So we the people of the global South and nations are no one’s backyard and no one’s front yard. We’re not the jungle surrounding the garden. We are representing the majority of the world and increasingly its economic engine, and we claim our rightful place in shaping history, in shaping the future, and pushing forward a new world order. And may we see this unfinished project of national liberation, most highlighted by the brave and courageous struggle of the Palestinian people, see its full conclusion. And may we all, comrades, mobilize towards the eventual and inevitable and necessary end to imperialism.

Leave a Reply