By Mehmet Enes Beşer

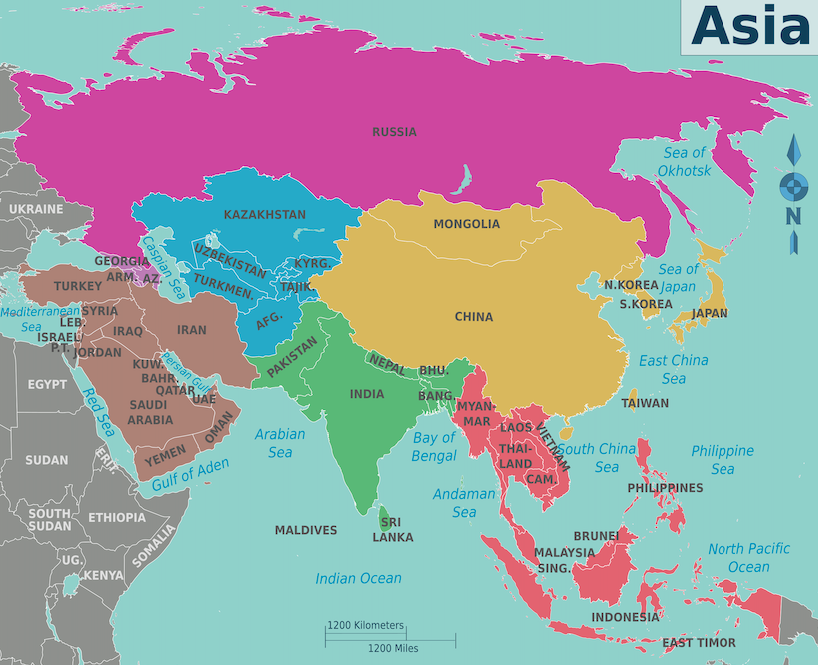

In the 21st century, Asia is not just on the rise—it is remaking the world order. Home to over half the world’s population, the world’s fastest-growing economies, and a rich cultural tapestry of civilizations, Asia is fast becoming the gravitational center of world politics, trade, and technology. But despite its enhanced centrality, Asia is still trapped in an old geopolitics script—where decisions on war, peace, commerce, and security are consistently made or vetoed by powers far away from its coast. In an era of increasing great-power competition, above all between China and the United States, the region is increasingly being used as a chessboard for foreign interests, rather than as a stakeholder in its own destiny. It is time to shatter that template. Asians must determine the future of Asia. It is the turn of countries in the region to reaffirm their sovereignty, remain outside the reach of alien control, and chart their direction on the basis of regional consent instead of transoceanic diktat.

Foreign meddling in Asia is rooted in distant history. Since colonial occupation and Cold War bipolarity, a majority of the region has traditionally lain within empires’ and foreign blocs’ spheres of interest. They have bequeathed political scars, unbalanced growth, and divided security environments. To this day, the majority of the local hotspots—Taiwan, the South China Sea, the Korean Peninsula, and so on—are driven not only by local tensions but by the continued intervention of powers thousands of miles away. This kind of engagement, typically concealed beneath the cloak of freedom, rule-based order, or collective defense, far too frequently is really all about national interest rather than regional stability. Long-term deployments of military bases, freedom of navigation operations, and policies of strategic containment are not politically neutral measures; they are politically motivated measures that limit the strategic agency of Asian states.

But Asia has changed. No longer the passive recipient of global design, the continent is now home to assertive middle powers, diplomatic entrepreneurs, and technologically sophisticated societies. From Indonesia and India to South Korea and Vietnam, Asia is replete with states capable of providing their own security challenges, negotiating their own disputes, and forging their own development models. Foreign troop stationing is more of a habit than a necessity—a hangover mentality which believes the Asians are incapable of looking after themselves unless the West or the East Pacific and the Atlantic instruct them.

There must be a clear shift towards regionalism now, but not as a posturing withdrawal gesture but as a positive turn. The rise of pan-Asian institutions and frameworks—like ASEAN, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—is proof that there is a changing appetite for intra-Asian cooperation. While these institutions are not perfect, they lay the groundwork for a new paradigm for diplomacy and management of conflict predicated on mutual respect, economic interdependence, and non-alignment. These mechanisms need to be reinforced, not under extra-regional arrangements such as the QUAD or AUKUS that can end up polarizing the region in the name of security.

Most importantly, at the heart of this regionalist imagination needs to be the rejection of strategic dependency. For far too long, nations in Asia have been bullied into taking sides in competitions not of their making. However, Chinese-American competition’s bipolar thinking is not conducive to polyphonic Asia’s agenda. Asia is diverse and not homogeneous but a composite of civilizations, states, and strategic options. The continent’s destiny cannot be predetermined by international ideologies or hegemonic alliances. Instead, what is needed is a coexistence model that features multiple foci of influence and respects each state’s sovereign options. This kind of vision can only be possible if the great powers vacate the ground and allow the region to find its own balance.

This is not a plea for isolation or a plea to turn the world’s face away. This is a plea to rebalance. Asian nations need to come to the world on the basis of parity, not as the appendages of someone else’s design. They must develop their own norms on cyber governance, artificial intelligence, climate action, and sea security—issues that will frame the century ahead. Asian values of harmony, community, and respect for sovereignty must guide the voice of Asia as it establishes these norms. From Tokyo to Tehran, from Delhi to Manila, intellectual and moral capital exist for formulating a collective vision of Asia worthy of the history and aspirations of the region.

Already, there are signs that this transformation is already underway. India’s inclination towards “strategic autonomy,” ASEAN’s claim to centrality, China’s focus on multipolarity all reflect a profound discomfort with the continuance of external tutelage. These national trajectories then must be sewn into this larger narrative of shared self-determination—one that is as meaningful for governments as it is for citizens, who must be capable of seeing their place make its own way unadorned by navies of foreign powers or enlightened designers.

Conclusion

Asia’s time has come—not merely regarding expansion and dominance, but regarding autonomy. The continent has endured for centuries under colonialism, Cold War rivalries, and foreign domination. It has endured having its fate discussed in Washington, Moscow, London, and Paris. All of that has to stop now. The new millennium has to be Asia’s—and not as a passive economic giant, but as an independent home of political innovation, cultural initiative, and strategic autonomy.

For that to be possible, Asian states must share the responsibility for leadership. They must eschew the allures of dependence, the delusions of zero-sum competition, and the satisfactions of extrinsic dependence. They must work on building regional institutions, solve conflicts through dialogue, and invest in widely participatory, locally rooted security frameworks. Most of all, they must learn to trust one another more than they trust the ones who come oceans distant with proposals wrapped in strategic calculation.

The great powers can continue to circle, but they will find a region less eager to be shaped and more determined to shape. Asia’s future is not a battlefield—it is a painting. And it is time that Asians themselves grasped the brush.

Leave a Reply