For an autonomous Mediterranean, the Italo-Turkish Axis as the core of a new geopolitical architecture.

For an autonomous Mediterranean, the Italo-Turkish Axis as the core of a new geopolitical architecture.

by Fabrizio Verde, Naples, Italy

In the current rapidly evolving global landscape, relations between Italy and Türkiye have gained increasing importance as both countries navigate the complexities of an emerging multipolar world. Geopolitical factors play a crucial role in shaping their interactions, as both nations seek to assert their influence in key regions and establish themselves as major players on the global stage. However, Italy has long seen its room for maneuver drastically shrink due to its subordinate relationship with the EU and the U.S./NATO alliance.

Italy and Türkiye share a long history of diplomatic ties and cultural exchanges, which have laid the foundation for a robust bilateral relationship. Both countries occupy strategic crossroads: Italy serves as a gateway to Europe, while Türkiye bridges Europe and Asia. This geographic proximity has led to closer economic and political cooperation, as both aim to capitalize on shared interests and align their policies in key areas such as defense, energy security, counterterrorism, and migration management.

An Increasingly Strategic Mediterranean

The recent summit between Giorgia Meloni and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has the potential to mark a significant turning point in bilateral relations between Rome and Ankara. The meeting, which resulted in new agreements on trade, technology, and infrastructure, should not be seen merely as a formal diplomatic gesture but as a symptom of a profound redefinition of the Mediterranean’s political geography. In an increasingly polarized international context, where Western powers seek to drag Europe into destabilizing conflicts, the Rome-Ankara axis presents a tangible opportunity to build an autonomous pole – independent of Atlanticist logic and open to a multipolar vision.

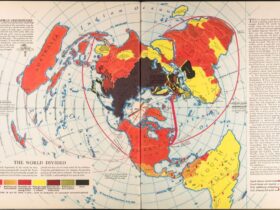

The Mare Nostrum is reclaiming its role as a focal point of global dynamics, not only as a vital trade route but also as an energy, geopolitical, and cultural crossroads. The Mediterranean today serves as a meeting point for Europe, Africa, and Asia, where competing interests collide: on one side, Atlantic powers (the U.S., France, the UK); on the other, emerging powers (Türkiye, Russia, China) that view the Mediterranean as a strategic bridge to Africa and the heart of Central Asia.

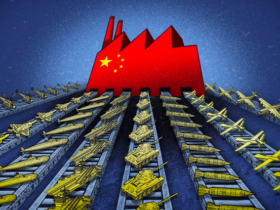

The exponential growth in trade flows over the past 15 years—driven largely by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—has transformed the Mediterranean into a key hub for global goods distribution. Türkiye, with its access to the Black Sea and the Levant, and Italy, with its Tyrrhenian ports and proximity to the Strait of Gibraltar, are central players in this scenario. Structured cooperation between the two could coordinate maritime hubs, improve trans-Mediterranean rail routes, and turn the basin into an area of collaboration rather than competition.

Economic Collaboration and Shared Security

Tangible outcomes of the summit include trade agreements such as the $40 billion bilateral trade target for the medium term, a Leonardo-Baykar joint venture for drone development, and plans for a trans-Mediterranean digital backbone via Sparkle and Turkcell. These initiatives extend beyond the private sector, reinforcing a shared vision of industrial and technological autonomy in the Mediterranean.

Cooperation in energy—from natural gas and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to renewables and hydrogen—further consolidates this partnership. Türkiye’s critical role in curbing irregular migration flows adds strategic value to the alliance in terms of security. But the potential goes deeper: an Italy-Türkiye partnership could redefine regional balances and counter external pressures from Washington and Brussels.

The Cyprus Question

While the summit did not address recognition of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), the issue remains a delicate and symbolic sticking point. Rather than reiterating conventional positions dictated by Brussels, Italy could seize this as a strategic opportunity. De facto recognition of Northern Cyprus would break with a decades-old European dogma that blocks pragmatic solutions—and weaken the Franco-Greek bloc, which, with U.S. and Israeli backing, seeks to isolate Ankara in the Eastern Mediterranean.

A bold Italian move would align with a multipolar approach prioritizing dialogue and cooperation among sovereign states over external interference. It would also strengthen ties with Türkiye, paving the way for deeper collaboration in energy, infrastructure, and defense.

Italy and Türkiye Toward Eurasia

Perhaps the most significant – and least publicly debated – aspect is the role Italy and Türkiye could play in forging a multipolar Mediterranean system open to cooperation with China and the broader Eurasian bloc. China’s growing influence in the Mediterranean – via investments in ports like Piraeus, Gioia Tauro, Valencia, and Alexandria – is an undeniable reality. United, Rome, and Ankara could champion a new regional architecture where access to Asian markets bypasses U.S.- and NATO-controlled corridors in favor of direct connections to Shanghai, Moscow, Tehran, and Islamabad.

Greater integration with BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) could offer Italy and Türkiye alternatives to the declining Atlantic order. Italy’s earlier participation in the BRI, for instance, delivered concrete economic benefits. However, the Meloni government has unwisely decided to withdraw from the New Silk Road agreement signed under the Conte administration.

A Counterweight to Brussels’ Warmongers

As Brussels doubles down on a foreign policy subservient to Atlanticist pressures – dragging Europe to the brink of economic and social collapse over the Ukraine war – Italy and Türkiye could offer an alternative vision: diplomacy rooted in dialogue, neutrality, and strategic autonomy.

The Ukraine conflict has not only pitted two nations against each other but also reinforced U.S. hegemony over Europe, weakened continental economies, and dismantled hopes of a culturally united yet strategically independent Europe. Italy, with its history of neutralism and Mediterranean vocation, could break this cycle – much as Türkiye has maintained bilateral ties with Moscow despite NATO membership.

Building a 21st-Century Equilibrium

Ultimately, Italy-Türkiye collaboration must transcend individual trade deals or joint statements. It should form the core of a broader vision: an autonomous, multipolar Mediterranean capable of mediating between blocs without permanently aligning with any. It must model interaction among sovereign states that prioritizes economy, culture, and peace over war and subordination.

To achieve this, Italy must take risks by adopting positions that may displease Paris, London, Brussels, or Washington. It must escape the ideological cage that reduces international relations to a binary of “good vs. evil” and embrace a foreign policy grounded in facts, concrete opportunities, and independent narratives.

Türkiye, with its geographic position, historical legacy, and ability to navigate diverse worlds, is the natural partner for this challenge. Together, Rome and Ankara could forge a new pole of stability in the heart of the Mare Nostrum, a pole that speaks Italian and Turkish but also listens to Russian, Persian, Arabic, and Mandarin.

Leave a Reply