The Missing Link in Global Climate Ambitions

The Missing Link in Global Climate Ambitions

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

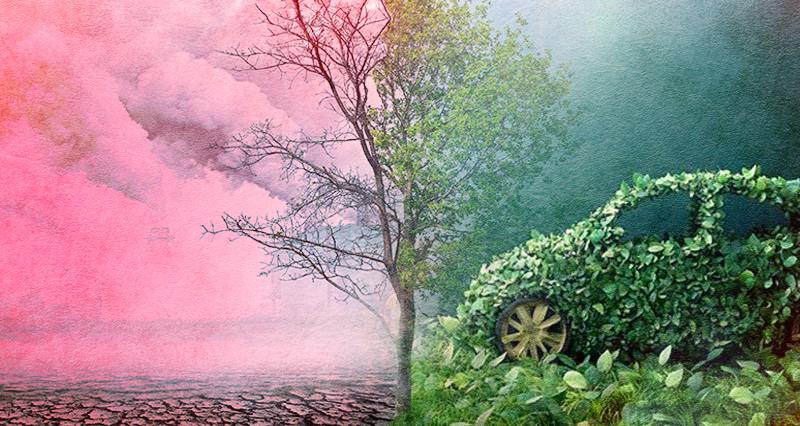

The green transformation in the car industry is no longer a vision of the future but a here-and-now necessity. Transport emissions account for almost a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, and the decarbonization of mobility is at the heart of both European and Asian climate policy. Rhetorical sustainability talk is now part of industrial policy on both continents, however, rather than the cooperative architecture—especially in the car supply chains—being still fragmented, precarious, and far from future-proof.

Europe and Asia both have complementary but not identical positions in the global auto value chain. Europe, led by Germany and Scandinavia, is expert in clean automobile design, standards of regulation, and safety norms. Concurrently, Asia, led by China, Japan, South Korea, and increasingly Southeast Asia, is the master of battery production, processing of rare earth minerals, and mass production of parts. If the goal is to build greener, more sustainable, and geopolitically resilient supply chains, then these two blocs must see themselves as not competitors, but co-designers of the new mobility regime.

This is easier said than done. Recent years have seen rising trade tensions, rising techno-nationalism, and protectionist industrial strategies such as the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act and the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. These measures—designed to secure domestic supply chains and reduce dependence on strategic rivals—have increasingly caused friction rather than cooperation. For China and wider Asia, the emergence of “friend-shoring” and demands for local content in Western markets has been a cause of worry about being left out of high-value parts of the green economy.

The risks of fragmentation are genuine, however. No country or region can produce by itself all the parts necessary for electric cars (EVs)—from semiconductors and lithium-ion batteries to high-tech software and green steel. Localizing full supply chains are not only inefficient economically but also environmentally counterproductive, potentially re-creating emission-intensive production models across borders. Further, the pace of climate deadlines—like the EU’s plan to end internal combustion engine passenger car sales by 2035—requires expediting, not industrial silos.

Asia–Europe cooperation must thus be redefined not just as a trade imperative but as a climate and security need. To begin, there are areas of common interest where both can benefit. Battery technology is a good candidate. While Asia is still dominant in battery manufacturing—China alone produces over 70% of global EV batteries—European carmakers bring technological complexity and growing regulatory pressure toward circular battery economies. Joint ventures that combine European ESG standards with Asian scale and efficiency can deliver products that are commercially viable and environmentally friendly.

No less important is cooperation in raw material extraction and production. The majority of the world’s cobalt, lithium, and nickel—precious inputs for EVs—are produced from politically unstable or ecologically fragile locations. Europe and Asia must cooperate to invest in green mining, secure diversification through joint ventures in Africa and Latin America and create open certification schemes. Initiatives such as the Global Battery Alliance and the EU–ASEAN Green Deal partnership can provide platforms for such cross-continental collaboration.

Digitalization presents yet another bridge for collaboration. As vehicles increasingly get software-defined, the automobile industry is increasingly integrated with digital ecosystems. Cybersecurity, autonomous driving algorithms, and data governance now determine the competitive edge of automakers. Here, Europe’s rigorous data protection rules and Asia’s fast-evolving technology landscape offer rich soil for collaboration on standards, interoperability, and regulatory convergence.

However, institutional trust is necessary for technology and trade collaboration to thrive. Having a Europe–Asia Green Mobility Council—consisting of governments, industry, civil society, and researchers—could institutionalize dialogue and nip conflicts in the bud before becoming broader trade issues. Such an institution could make efforts to coordinate environmental standards, align incentive frameworks, and synchronize public investment in EV infrastructure, such as cross-compatible charging systems.

Small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) should not be left out, either. They are generally the weakest point in global supply chains, but are full of potential to innovate and create jobs. Bilateral funding initiatives, green technology transfer projects, and matchmaking platforms can help SMEs from both hemispheres to engage better with the world green auto industry.

Above all, the conversation on green automotive supply chains has to engage the Global South. Southeast Asia in particular is being made into a production hub and an up-and-coming consumer marketplace in the forthcoming. Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam are presently making investments into battery hubs as well as EV manufacturing plants that tend to be funded by European or Asian funds. Ensuring these economies gain not only menial assembly employment but also due to technology transfer and value capturing is paramount in making a fair green transition.

The global contest toward electric mobility is also an innovation test in terms of institutional forms and political imagination. Asia and Europe have the technology, aspiration, and money to drive the transition but fall short on developing the infrastructure of trust, cooperation, and cooperative governance necessary for connecting these continents. Without that, green value chains will instead become battlegrounds of rivalry and exclusion rather than cooperation and inclusivity.

In order to flourish, both continents have to move beyond transactional trade and embrace strategic interdependence. That is to pair up climate ambition with trade policy, invest in common standards, and establish platforms for enduring conversation. It means accepting not only but celebrating each other’s weakness—Asia’s manufacturing prowess, Europe’s regulatory fineness, and the innovative strength of both continents.

Green growth is not going to be driven by supply chain nationalism or isolationist industrial strategies. It will be driven by collaboration that recognizes the complexity of value chains today and the urgency of the climate crisis. At its core, a greener automobile future is not about building more efficient cars—it’s about forging better connections. And to accomplish that, Europe and Asia need to drive together.

Leave a Reply