Changing Priorities from the Monroe Doctrine to Trump.

Changing Priorities from the Monroe Doctrine to Trump.

By Orçun Göktürk

The foreign policy of the United States (US) has gone through various phases throughout history, establishing itself as a dominant imperial power both on its own continent and in other regions of the world. The evolution of US foreign policy, particularly through a strategy of dominance over maritime routes and ports, has taken on a new dimension in today’s multipolar world, especially in the context of competition with China.

During the Trump era, US foreign policy strategy has seen significant shifts driven by realpolitik, challenging traditional norms and altering America’s global role. Trump’s claims over Canada, Panama, and Greenland, along with his attempts to rename the Gulf of Mexico, suggest that the Atlantic alliance could be entering a period of fragmentation far beyond mere distrust. To better understand Trump’s foreign policy, we must examine the key strategic turning points in history of US international relations.

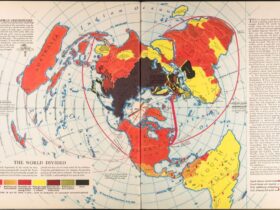

The Monroe Doctrine (1823): Protecting the American continent

The foundation of US foreign policy was laid with the announcement of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. Under President James Monroe, this doctrine rejected European imperialist intervention in the Americas, declaring that the continent should remain within the US sphere of influence.

This policy was a product of the US’s focus on continental priorities at a time when it was still economically and militarily weak. The Monroe Doctrine served both as a defensive strategy and as a long-term imperial objective, reflecting America’s ambition to establish dominance over the Western Hemisphere. The principles of “isolation” or “non-intervention” included in the doctrine were, in reality, a reflection of the US’s temporary pacifist stance, which it was “forced to adopt” until it gained sufficient power. Throughout the 19th century, the US remained largely dependent on the British Royal Navy while working to build its own military strength.

Turning point: The 1895 Venezuela Crisis

By the late 19th century, the US had begun to implement its foreign policy in a more active and aggressive manner. Having achieved the anticipated economic and military development, the Monroe Doctrine underwent changes.

In 1895, European powers sought to exploit newly discovered valuable minerals in Venezuela and expand their influence in the Caribbean. The US perceived this as a direct challenge to the Monroe Doctrine and intervened in a border dispute in Guyana, taking a stance against Britain.

This crisis accelerated the recognition of the US as the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere. British Foreign Secretary Lord Salisbury’s admission that “The US has now become the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere” marked the beginning of a new era. Following this event, the US pursued policies that expanded both its economic and military power in the region.

Roosevelt and a new phase

Under President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, the Monroe Doctrine was reinterpreted through the Roosevelt Corollary. This new doctrine asserted that the US had the right to act as an “international police force” in the Western Hemisphere whenever conflicts or interventions arose.

This shift paved the way for the US to become a global power, increasing its economic and political influence in Latin America. Roosevelt emphasized the importance of controlling maritime routes and ports, leading the completion of the Panama Canal project. The canal’s construction enabled the US to establish strategic dominance between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, both economically and militarily.

The Trump Era: A global contraction strategy

Under Donald Trump’s presidency (2017-2021), US foreign policy entered a new phase. His “America First” slogan reflected a strategy in which US international interests were largely defined by economic and military priorities.

The clearest example of this shift was the US’s withdrawal from Afghanistan following the 2020 Doha Agreement with the Taliban, which was widely perceived as a US defeat.

With Trump’s re-election in November 2024, his proposals—such as buying Greenland, emphasizing control over the Panama Canal, and attempting to rename the Gulf of Mexico—suggest a growing US focus on securing maritime routes and ports in its immediate surroundings.

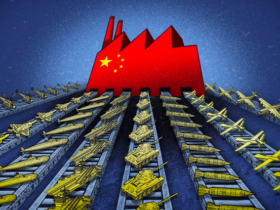

China’s increasing influence in global trade routes, particularly through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and its rise as the world’s leading naval power may have pressured Trump to develop regional strategies. The “Indo-Pacific Strategy”, which involves forming alliances to counter China’s growing maritime dominance and increasing the presence of the US Navy in the region, underscores the intensifying competition between the two superpowers.

Stopping decline through a ‘perimeter’ strategy

US foreign policy has historically been built upon a doctrine of “dominance” that began with the Monroe Doctrine and evolved through the Roosevelt Corollary. During the Trump era, the US adopted a “global contraction strategy” to protect its interests in a multipolar world and developed new competition strategies centered around maritime routes. The effectiveness of this strategy against China’s rising influence will depend on how global power balances shift in the coming years.

Recently, Chinese President Xi Jinping inaugurated a $3.5 billion container port on the coast of Peru, reducing shipping times by 23 days and cutting logistics costs by 20%. In the US, this development has been met with concern, with analysts stating, “The power we used to challenge Britain with is no longer ours. Ports built with Chinese financing pose a significant threat to our hegemony.”

Ironically, before confronting Soviet Russia and now China and other developing nations, the primary forces that the US struggled against in the 19th and early 20th centuries were European imperialist powers—particularly Britain—from which it emerged and whose political, economic, and cultural systems it closely resembled. The US initially challenged European powers under the claim of “building a better version of their system.” After World War II, it consolidated these European forces under the guise of “defending against the communist threat” posed by the Soviet Union. However, this system is now falling apart, and Trump is its clearest manifestation.

Today, the US faces an unprecedented “threat” from China, rising Eurasian powers, and supporters of this shift across Africa and Latin America.

Which Europe?

Those who call this a “New Cold War” are making a historical mistake. Unlike the Cold War era, there is no Europe to consolidate against China using the pretext of “communism”—nor can the US rally Japan, India, South Korea, or other Asian powers in the same way.

Trump, recognizing the decline of American imperial dominance, seeks to enforce his strategy through power politics rather than ideological consolidation. This is why he has trampled on liberal values such as democracy, rule of law, and human rights, which were once championed by the US as instruments of influence in Europe. Liberal Europe does not support Trump, so there is no Europe left for him to win over.

Thus, Trump’s focus on securing the US perimeter—with policies involving Mexico, Panama, Canada, and Greenland—takes priority over attempting to “win over” Europe. The rise of nationalism and anti-NATO sentiments within Europe leaves the US with limited options to develop a new strategic approach toward Europe.

Leave a Reply