On July 13th, 2018, the finalized text of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) was produced by the United Nations, following two years of official preparations which concluded in Morocco. While officially portrayed as a united effort to overcome humanitarian problems associated with skyrocketing migration and refugee crises, particularly in and around Europe, the document, which is supposed to be recommendatory in nature, has been a matter of heated controversy. And this “recommendation” now has a rebellion on its hands.

The United States quit participating in talks back in December 2017, with Tillerson declaring that such “could undermine the sovereign right of the United States to enforce our immigration laws and secure our borders.” Another Anglo-5 member, Australia, soon refused to sign the pact, with PM Dutton stating in similar language: “We’re not going to surrender our sovereignty – I’m not going to allow unelected bodies to dictate to us, to the Australian people.”

Continental Europe has also rebelled against the pact: Hungary denounced the agreement as a “threat to the world”, and FM Szijjarto even ventured to assert: “We consider migration a bad process, which has extremely serious security implications.” Austria, too, resigned from negotiations, citing concerns over sovereignty. Austria’s Croatian neighbor’s president subsequently promised to not sign the “Marrakech Agreement.” Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis then stated that he “does not like” the pact, and called on the Czech government to “act in the same way as Austria or Hungary.” Finally, at a press conference with Angela Merkel just the other day, Poland’s PM Morawiecki proclaimed that it is “very unlikely” that Poland will accept the global migration pact.

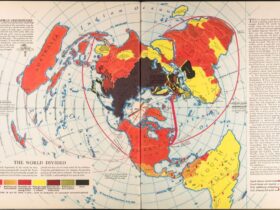

In other words, two of the foremost challenges in 21st century international relations and geopolitics – sovereignty and migration – have been cited by a number of European countries against a Europe-centered United Nations “recommendation.” This is no mere coincidence. To understand the significance, and interconnectedness, of this clash, however, it is necessary to first take an abridged trip down European memory lane.

“Sovereignty”, in its predominant Western European legal conceptualization, arguably owes its origins to the medieval conflict between burgeoning European monarchs and Papal authority, in the context of which “Sovereignty and self-determination have…functioned as a mediating ideology, reconciling the juridical means for attaining hegemony with the opposing need to project the rights and obligations created for the other as objectively derived from universal values.”[1] In contrast to the Byzantine Empire, where “sovereignty” was conceptualized in the notion of the “symphony of powers”, where the emperor and patriarch exercised cooperative authority, in Western Europe the rebellion of monarchs against Papal supremacy yielded the need for a doctrine of authority that could tip the balance of the mediation between unequals. Thomas Hobbes’ (1588-1679) seminal declaration of “absolutist” sovereignty for monarchs surrendered by the king’s subjects by a “social contract” attempted to systematize sovereignty somewhere in the middle of this dialectic by shifting the emphasis to sovereignty necessitated in face of a universal “state of nature” of “of every man against every man.”

In other words, the sovereign state was seen as a necessary “compromise” in human history. With the official removal of the explicitly religious obligations of sovereignty following the Thirty Years War, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) could therefore assign sovereignty to the “will of the people” in accordance with increasingly secularized Protestant ethics manifest in Western “rationality.”

Just how this “will to sovereignty” could be expressed, through what mechanisms, and to what extent, was suspended in ambiguity, ultimately leading the seminal 20th century theoretician of sovereignty, Carl Schmitt (1888-1985), to conclude that “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” [2] Since Schmitt’s formulation, a number of varying interpretations of sovereignty have been put forth, on which there is no consensus. But, more importantly, the practice of sovereignty in international law has become glaringly unambiguous: the 2001 International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty and 2005 “Responsibility to Protect” doctrine enshrined the legally unsubstantiated precedent for discarding the uneasy balance between state sovereignty and self-determination in favor of unipolar hegemony, i.e., the “right” of “responsible” (read: Western, Liberal, Atlanticist) states to override the sovereignty and self-determination of others in accordance with their exclusive, “global” view of human rights and “state-building”.

Sovereignty was therefore made the privilege of the few, and this privilege was dressed up in humanitarian terms, a danger which Schmitt also discerned: “If one begins to act in the name of all humanity, on behalf of abstract humanism, in practice this means that this actor denies all possible opponents the claim to having human qualities at all, thus declaring himself to be beyond humanity and beyond law, and therefore potentially threatens a war which would be waged to the most terrifying and inhumane limits.” The consequences of this precedent in North Africa, the Middle East, and Ukraine, where formerly sovereign, recognized states have been reduced to “failed states” in a vicious, self-fulfilling prophecy, are well known.

But the unipolar, global hegemony of Atlanticism is, by all accounts, in decline, and has been accompanied by a similarly dire crisis of the ideology employed to legitimate such “sovereignty”, Liberalism. Few honest analysts today would dare to deny that Western formulations and codings of “sovereignty” have been exhausted, and that the de jure and de facto sovereignty of Western states over others is being irreversibly challenged by the rise of a number of states, actors, blocs, and integration processes which were not accommodated for in the plan for a “New American Century.” Or, in the admissions of two US National Intelligence Council documents:

“The international system…will be almost unrecognizable by 2025…By 2025 the international system will be a global multipolar one”, in which Western concepts “will not necessarily provide the dominant underlying values of the international system.”

Most famously, ironically, and tellingly, the United States itself, under Trump, has cited “sovereignty” to resist the very international order which the US established post-World War II. In another telling case, the secession of Crimea from Ukraine and its reunification with Russia was widely condemned by the Western “international community”, even though the Crimean parliament cited the Kosovo precedent established on the initiative of these Western states themselves. In a word, the historical Western theoretical and practical precedents of “sovereignty” are increasingly out of step with the realities of a world order that is heading towards multipolarity, in which any “collective West”, and much less any one “Western state”, is unlikely to be a dominant player in international relations, against whose paradigm “sovereignty” is increasingly being evoked…now from the inside out.

It is probably no coincidence, therefore, that the Western, European birthplaces of the modern concept of “sovereignty” are being confronted with this crisis head-on in the case of migration. Indeed, it is precisely the profound demographic transformations which European countries are undergoing in relation to immigration, and their heatedly debated cultural consequences, that have now been recently challenged by a number of states under the slogan of “sovereignty.” How exactly “sovereignty” has become entangled with contemporary migration processes, what exactly these “migration processes” are, what the claims to “sovereignty” in the face of them tell as about current geopolitics, and how European political discourse on both migration and sovereignty might change in the present rebellion against the Global Migration Compact will be explored in part two.

[1] Siba N’Zatioula Grovogui, Sovereigns, Quasi Sovereigns, and Africans. Race and Self-Determination in International Law (University of Minnesota Press: 1996), 16.

[2] Carl Schmitt, Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty (MIT Press: 1985), 5. In this brief discussion of the conceptualization of sovereignty, I am indebted to the Russian political scientist Leonid Savin’s forthcoming book on multipolarity.

Leave a Reply