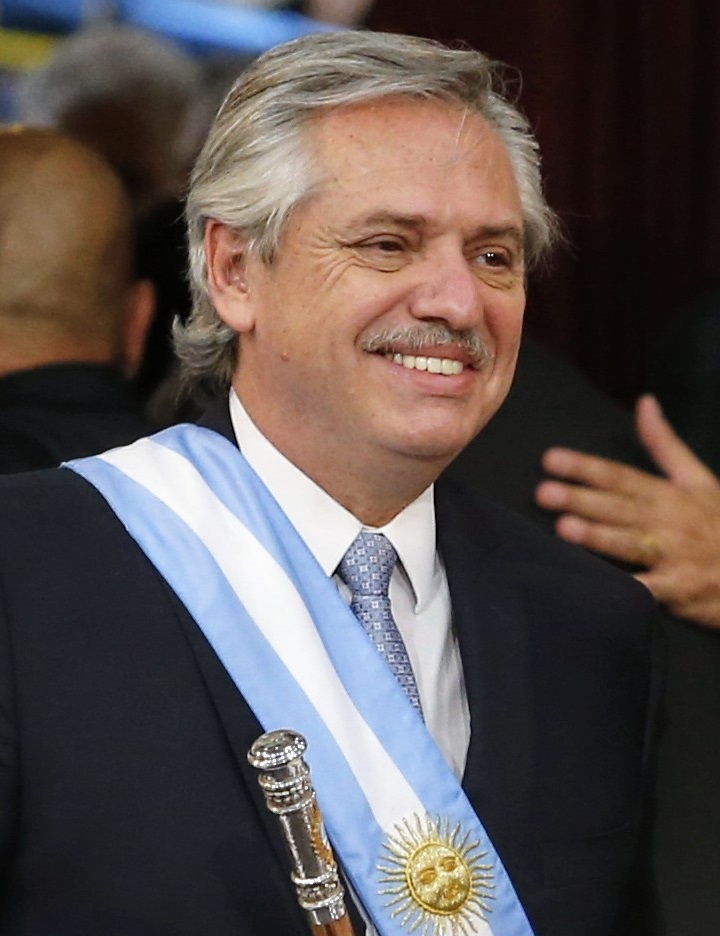

Alberto Fernandez’s government has been safeguarding a successful response to the crisis unleashed by the pandemic. While certainly not without difficulties, he is showing the capacity for resolution, elasticity and adaptability. The historic Peronist party in power has found itself at a critical moment. Successfully emerging from the crisis would be a huge political victory, and would undoubtedly have serious regional consequences. In post-pandemic Argentina, a sovereign popular experience could consolidate and recalibrate the region as a whole at the very point it appears more unstable than ever. The economy and creation of wealth in the country, much like everywhere else, is going to prevent a serious challenge in the coming days.

Alberto Fernández recently became president after four years of Mauricio Macri’s government which was essentially right-wing neoliberalism in alliance with conservative sectors of the population and, of course, forces within the financial world. Macri’s government engaged in a phenomenal plundering of the country’s wealth and leveled a fierce attack on the rights of the poor and the working class. The neoliberal system facilitated an enormous transfer of resources and wealth to the ruling classes, and as if that was not enough, nonetheless plunged the country into unparalleled indebtedness: public debt grew 40% between 2015 and 2019 (reaching $ 337 billion dollars), raising from 53% of the GDP to 93%. This money essentially went up in smoke as it was sent to the offshore bank-accounts of the ultrawealthy while unemployment rose to 10.9% and poverty levels 40%.

Fernandez, who started his government in December 2019, has been taking measures to prevent the country from collapsing due to hyperinflation, unemployment, mass unrest, hunger and poverty. At the same time, the new government sought to stabilize and reactivate at least portions of the domestic economy, which was essentially going into a tailspin when he took office. Domestic demand plummeted long ago, and given new changes and challenges, it is all too clear that arduous tasks lie ahead for the South American nation.

Wikimedia Commons

A CHANGING SITUATION

The coronavirus outbreak and the government’s forced response created totally new conditions in the country. Since the very beginning of the pandemic, Fernandez has made it clear that his main focus is containing the infection, fighting the epidemic and preserving the health and life of his population. However, the devastating implications of this policy for the country’s economy are only becoming more complex as the situation develops. Recent forecasts by The Economic Intelligence Unit (the research and analysis division of Economist Group) indicated that by 2020, the global economy will contract by 2.2%. The Latin American region, which has 190 million poor people, will contract by 4.8%. The worst performance forecast is for Argentina, which is predicted to experience a 6.7% drop. A huge fall in international trade and commodity prices is expected. The income generated by exports from the agro-industrial complex, essential for the country’s productive scheme, could fall by as much as 25%.

Given the lack of success among opposition groups, the situation created by the pandemic might ironically benefit the country’s new leadership, helping the President’s power to grow and consolidate. However, this kind of development is anything but set in stone. Given that no one foresaw the coronavirus outbreak, we should consider it equally impossible that anyone will be able to predict the outcome. If the situation grows further out of control across the planet, that confusion is likely to continue. This is why drastic measures have been implemented in many countries, especially in light of situations that developed in places that were caught unprepared such as Italy and Spain.

Fernandez is a politician who seems poised to take hold of the situation, relying on an extensive network of political operatives that are now demonstrating their capabilities intandem with the main political leaders in charge of provincial and municipal governance. His decisions appear to be sound, especially in light of what other leaders have proposed. The national government hit the ground running: strong measures were taken at the very beginning. A few days after the Pandemic was declared (March 11), mandatory stay-at-home orders were set up nationwide (March 20), driving most of the population into seclusion, restricting travel and forcing the closure of businesses. The situation was monitored with the help of data from people’s smartphones, including facial-recognition cameras and self-reported body temperatures. People reacted positively to the restriction measures. Day-to-day actions are carried out in a context of a broad political and social consensus, making the measures far more efficient. While it seems that the peak of infection is now flattening (on April 12 there were 2,142 infected with 89 deaths reported).

Argentinians are heavily reliant on their public national health service that has resisted neoliberalism attacks throughout the years. Although plagued by problems due to privatization and lack of financing, the system is still an extended network that includes different levels of health facilities, high complexity standards, extensive scientific experience and a large professional staff. The Health Ministry is constantly working, multiplying beds and field hospitals (empty at the moment), health posts, control systems, supply, scientific research, prevention and cleaning.

CONSENSUS FOR THE LOCKDOWN

There was consensus all along the political spectrum and among most communities to extend the existing lockdown for two more weeks (and they will surely be extended again until May), but the government has indicated it will take robust steps to respond to the resulting economic situation for a long time after. Slowly and progressively, some service branches and essential activities will be reactivated, according to the strategy commanded by the national government, in spite of pressure from big finance and the business lobby. Productive sectors seem not to have proposals on how to prop up the economy, even in their own branches… with the notable exception of the shameless liberals who are now suggesting that if the lock-down continues, companies will need to ask the state to pay their employees’ wages and demand government bailouts. These figures clearly live according to the principle that “profits should be privatized while losses are socialized.”

From the beginning of March, a situation has been taking shape wherein certain political and economic proposals that were timidly outlined in the pre-pandemic era –and much criticized- are finding new ground and gaining momentum due to solid support from civil society. For example, the government’s reactivation of the internal market is now a central state policy; government stimulus for increasing domestic demand is something that was violently fought by the Macri administration during all its four years of government, but now, even in the mass media, it’s difficult to find arguments against fiscal deficits being financed through money creation, suggesting the idea has been re-legitimized. The mass-media was particularly attentive to the President’s remarks regarding the state’s debt issue, which he suggested would no longer be a priority while more pressing issues are resolved.

He did suggest that there would likely be a forced renegotiation with international creditors. In other words, Argentina is going to delay a large part of the $10 billion dollar debt payments covered by local law until 2021, unilaterally changing the terms of the contract. Likewise, the state emphasized price control and suggested taxing the top 1% of the population, both individuals and legal entities. Debate on the nationalization of companies administering public services has yet to be opened.

Pixabay

ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE FROM THE STATE

Meanwhile the state is supporting millions of families, ensuring their salaries (civil servants, teachers, retirees, pensioners); avoiding dismissals; helping to pay private sector salaries; granting subsidies to small self-employed and poor or unemployed families (11.3 million people will receive the equivalent of $ 150 in April/May as Emergency Family Income). Emergency aid is being dispensed by reinforcing the monthly family assistance per child with a slight increase and a massive distribution of food to families who rely on subsidies. The government has extended the deadline for some business and personal taxes. The Central Bank has already ordered private banks to finance credit card maturities with a three-month grace period and various fees.

There is the pressure from corporations and businessmen who lack any historical sense and have no commitment to the future of the nation, but a great deal of power within the framework of an economy where monopoly logic is very strong. Some business sectors in Argentina, for example, have begun a counter-offensive, yet there have been no major repercussions in the media or popular consensus. An underground group of big businessmen called for a tax rebellion, private banks refused to grant cheap loans to small businesses so that they can pay wages in the coming days…. the situation is changing every minute.

The middle classes, which historically have been integrated into the same bloc with big business and major corporations, have also begun to exert pressure. Anti-populist rooted business and self-employed sectors want to instigate fiscal rebellion, slamming the state because they believe they already pay a great deal of taxes and now, in facing the crisis, they have simply stopped receiving income and believe the state is not doing enough for them. They are definitely a power-factor, by quantity, by participation in the economy as part of small and medium-sized enterprises and because they tend to overdetermined reality by presenting themselves as role models for ideal citizenship. However, the contagion has also had its effect on these sectors and many have begun to weigh the role of the state from another point of view: they need it and are now demanding action and resolution.

The counteracting pressure from below is still to be felt. At the level of territorial executive power, mayors have been working without respite since the declaration of the pandemic by the WHO. They are a factor of great importance in the country’s political scheme, especially in large urban agglomerations where the delicate balance is more likely to break. Together with the provinces’ governors, they are in charge of the situation and ultimately responsible for the emergency mechanisms at the ground level. Trade unions are central actors as well. Argentina’s trade unions are powerful organizations with vast resources and negotiating power. They are working alongside the state in crisis management efforts, having made their structures available to the government and playing a role in territorial social containment. The country has a political culture rooted in the popular sectors, having been born of organizations for the unemployed at the end of the 20th century. Since then they have been playing a role in caring for the marginalized and excluded, while exercising political functions by exerting pressure and proposing progressive transformations in both the social system and the state. Some of these structures have dissolved while others were integrated into other kinds of organizations or the Fernandez government. Some of them, by becoming bureaucratized, have come to play a role in containing class conflict, serving as a part of the government or aiming to install their leaders as public officials. The Army and the Catholic Church are also working under the president´s coordination efforts by providing infrastructure and reaching out to poor families.

The pandemic and the resulting isolation measures will surely deepen the levels of poverty and misery experienced in the most humble neighborhoods in the country. Many people depend partially or completely on the sustenance and assistance of state or civil society community networks such as soup kitchens. The demands of this section of society are about to increase dramatically.

Taken together, the executive levels of the state, the unions and the people’s organizations in their various experiences, seem to be forming a power structure with enormous territorial scope that might be turned into an asset for the country in resisting the pandemic, not only by sustaining a vital functioning of society and taking care of it in an emergency situation but also by confronting the pressure of dominant sectors that seek to defend their private interests and avoid state control, engage in mass layoffs or cut people’s salaries. In other words, these sectors do not want to bear the costs of the crisis. Some trade unions have been negotiating with employers. Others, such as militant Truck Drivers, have already declared that they will not accept layoffs nor wage cuts. The jobs at risk number in the hundreds of thousands.

STRONG STATES, STRONG LATIN AMERICA

Meanwhile, the state is back to playing a leading role in Argentina, and the Peronist party is only being strengthened. In the face of the crisis catalyzed by the coronavirus, possibilities to install the necessary structures to consolidate a sovereign state have opened up, bolstering its base of popular and democratic rights (e.g., public health and education, a strong domestic market, care for the marginalized, government intervention in markets, domestic production and job creation). Peronist Argentina is looking for solutions that will take the country beyond the era of global Unipolarity. Accomplishing this, however, will depend on popular participation and strong anti-imperialist projects.

The pandemic has all but proven that the Peronists are the only party capable of leading the country, especially given the uncertain economic horizon where no one can guarantee success. What Fernandez had initially presented as tests or reparative measures is now becoming a solid, accelerated empowerment process mediated by the state. The country seems to be following the path of social responsibility, creating a domestic structure where talk of moving toward self-sufficiency is already in public debates. However, it must be made clear that Argentina cannot survive without the rest of the world, especially given the current dependence of the country’s economy on other states.

These are some of the features needed for Latin America to develop a strong and independent position in a multipolar world. Perhaps some of these new, stronger states which are concerned about the welfare of their populations above all and hope to move away from globalism and imperialism will push for a reconfiguration of regional integration processes, resulting in a geopolitical turning point for the region. Argentina and Brazil have been granted the chance to become geopolitical vectors of change. By taking a new direction, they could fight against US’ aggression in Venezuela, recover experiences from regional integration projects such as UNASUR and CELAC, deepen the articulation of the ALBA-TCP, re-found MERCOSUR, and, in Argentina’s case, perhaps even reorient back toward the BRICS framework.

Leave a Reply