In Ethiopian Prime Minister Abi Ahmed’s recent statement he confirmed that his country would start filling the reservoir of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in the coming rainy season. This was only the latest episode in a policy already considered fait accompli, the culmination of Addis Ababa’s actions against the rights of countries downstream the Nile.

The Ethiopian authorities recently reduced the number of electricity generation turbines in the Dam to 12 from 16, which means that the amount of electricity generated will decrease to the point of making it economically ineffective, and thus confirming its aim was not generating electricity at all.

If these two developments are added to Ethiopia’s evasion from signing the recent agreement reached between the downstream countries (Egypt and Sudan), sponsored by the US Treasury and the World Bank, to define the rules for filling the dam reservoir, it becomes clear that Addis Ababa is only procrastinating to avoid any written commitment that guarantees no harm will come to Cairo, and that Ethiopia is attempting to achieve goals unrelated to development and not supported by international law.

A STRATEGIC GAME

Ethiopia took advantage of the January 25, 2011 revolution in Egypt and the deteriorating political situation in the country to violate all the rules of international law regulating international rivers on the Nile.

Addis Ababa has continuously tried to evade compliance with international agreements that estimate Egypt’s water share to 55.5 billion cubic meters annually, claiming that these agreements, specifically the 1929 agreement, harken back to the era of colonialism, in a clear violation of international law that maintains such agreements until they are replaced by new agreements.

The most important item contained in the 1929 agreement is that a prior agreement with the Egyptian government is required before any actions on the Nile and its branches or on the lakes from which it originates that would reduce the amount of water that reaches Egypt or modify the date of its arrival or reduce its level in any way harms Egypt’s interests.

Addis Ababa propagated the idea that Egypt was trying to monopolize the waters of the river and preventing Ethiopia from its right to development. This is something that Cairo practically refuted by signing the Declaration of Principles agreement in 2015, which recognized Ethiopia’s right to construct the dam in exchange for an Ethiopian pledge not to cause serious harm to Egypt while filling the dam reservoir.

ENERGY WARS

Since then, Ethiopia in its negotiations with Egypt and Sudan has worked around the rules and mechanisms for operating and filling the dam reservoir, a strategy for buying time in order to disclaim any obligations not to harm Egypt and its water rights.

Throughout these years, Ethiopia has given political and internal pretexts to postpone the negotiation meetings, again and again. It also delayed the process of appointing the consulting office mandated to present a comprehensive study on the construction safety of the dam, which is very necessary, especially since the land on which the dam is located is geologically very dangerous.

Despite many technical notes made by the French consulting office B.R.L. regarding the issue of security and safety of the dam, Ethiopia has refused to abide by them, claiming they are not binding, although failure to adhere to them makes the dam’s collapse possible at any time, threatening to flood Sudan and Egypt and destroy hundreds of villages and cities in both countries.

With Ethiopia evading responsibilities time and time again, Egypt has pressured it to activate the agreement of principles and accept a third party into the negotiations. After long hesitation and reluctance, Ethiopia reluctantly accepted the US as a mediator and the World Bank to bring the views of the two sides closer.

Indeed, Washington was able to draft an initial agreement that addressed the concerns and interests of the three countries. Although Ethiopia acknowledged that the agreement ended the disputed points, it evaded providing a signature.

After that, the government of Ethiopia launched propaganda portraying itself in the role of the victim and defaming its opponent (Egypt) by claiming that Cairo rejects Addis Ababa’s right to development, a false claim.

Ethiopia also denounced the appointment of the US as a mediator, something that it itself had accepted and with which they had already interacted for months. Ethiopia sought to pit African countries against Egypt by providing half-truths, even seeking South African mediation.

The Ethiopian propaganda was based on claiming sovereignty of the dam and the river, which is opposed to the rules of international law that classify the Nile as an international river to which the rules of international rivers must be applied, meaning that there is no possible sovereignty to be granted to one country.

This Ethiopian propaganda and attempt to return matters to square one, in addition to the statements issued by its officials that the dam will be built and will be filled without the need for an agreement, reveal conclusively that the issue is not about development or electricity generation.

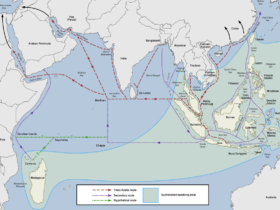

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE NILE RIVER

The huge dam that Ethiopia is building on the Nile, which will hold more than 70 billion cubic meters of water and will make Egypt lose more than a half of its water supply, is not just a step in the east African country’s effort to maximize its production of electricity. It is also not an attempt to maximize its benefit from the waters of the Nile as a natural resource. Perhaps this would be true if there were no alternatives to achieve the two goals in more economical and feasible ways.

Wikimedia Commons

The Ethiopian categorical rejection of all the alternatives proposed by Egypt – as the largest affected by the construction of the dam – to generate electricity by declaring its readiness to participate in building and financing smaller dams capable of producing quantities of electricity equivalent to or greater than expected from the Ethiopian Dam currently being constructed, further suggests that there are hidden motives.

Many observers say that Ethiopia aims to monopolize the waters of the Nile in order to turn it into a commodity, and thus force others to buy it. This is extremely dangerous politically and socially, especially for Egypt, which has no other water sources than this river and has a population of more than 100 million.

Egyptian officials have privately said that the goal is more than water, and that Ethiopia seeks to weaken the political and geopolitical weight of Egypt by hitting its development, giving Addis Ababa political levredge in relations with the rival state, giving him more influence than any other foreign governments.

Observers agree that the Ethiopian game has been carefully designed, as Egypt’s geopolitical weakness would be in Ethiopia’s interest as the country seeks to expand its influence.

Although Cairo understands that these are Ethiopia’s intentions, it has nonetheless engaged in serious negotiations, sensing the danger of filling the dam very quickly in the coming years, and fearing the impact on its fair share of river water during that process.

While the Ethiopians want to fill the dam in 7 years, Egypt believes that should happen in a period ranging between 12 to 21 years to reduce the impact on the water supply.

The main problem related to the dam is the years of prolonged and severe droughts that create risks to water flows during and after filling it; and since prolonged drought will inevitably occur at some point in the future; many water experts argue that the effects and consequences of drought have to be carefully managed, and that its potential should be addressed explicitly in the ongoing negotiations on the Nile waters.

For those who do not know, the Nile is the main source of life in Egypt, and therefore Egypt’s insistence on obtaining written pledges from Ethiopia that guarantee it comes to no harm is a natural and logical matter consistent with international law.

MILITARY OPTIONS

The Ethiopian evasion of any written pledge places the Egyptian state in front of difficult choices:

1 – Complying with the desire of the Ethiopians to fill the dam reservoir quickly, threatening drought for thousands of villages, set-aside more than a million acres and losing some 5 million jobs.

2 – Any other Egyptian options to address its concerns about the dam using a fourth mediator or internationalizing the issue before the Security Council will not address the element of time that Addis Ababa has on his side.

3 – As for resorting to the International Court of Justice, this path requires the approval of the Ethiopians, which they are unlikely to provide.

4 – As a result, the military option of bombing the dam is likely the most direct option.

This fourth option was raised following the Ethiopian’s evasion of signing the last agreement dealing with filling the dam and the rules for operating it. However, is Cairo likely to make this decision?

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi stressed that Egypt will take all necessary measures to protect its rights in the waters of the Nile, indicating that no scenario would be excluded.

On the other hand, in October 2019, the Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abi Ahmed, told the Ethiopian Parliament that there is no force that could prevent Ethiopia from building the dam, threatening to collect a million Ethiopians to go to war if need be.

The International Crisis Group also warned in 2019 that the two countries could be drawn into the dispute over the dam.

Although observers believe that water diplomacy is capable of defusing the war between the two countries, a war scenario is not impossible, although it would be complex in both military and international terms.

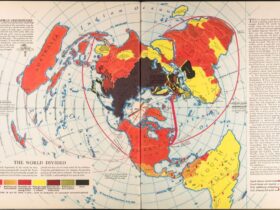

There are no land or sea borders between Egypt and Ethiopia, and therefore the bombing of the dam needs a professional military scenario that takes into account complex political and geographical calculations.

Before resorting to such a scenario, Egypt needs to present its case differently to the international community, emphasizing the fairness of its cause and its water rights guaranteed by historical agreements and rules of international law.

Egypt needs to present the issue as one that threatens regional and international peace, security and stability, which it actually is. This course will help the international community accept any military scenario if Ethiopian intransigence persists.

Cairo must make it known that the lives and livelihoods of millions of civilians is at risk in the most populous country in the Middle East, the disruption of which could instigate the largest wave of migrants ever to the countries of the region and Europe, something the world would be unable to handle.

Furthermore, damaging the geopolitical weight of Cairo would further confuse a situation already embroiled in the chaos of the Arab Spring revolutions.

Cairo must also show that if it decides to proceed with a war scenario, the vital international trade route through the Suez Canal and along the Horn of Africa could be threatened.

All of these points will hopefully persuade the world to intervene to prevent the emergence of Ethiopia as a new rogue state in Africa which ignores the rules of international law and international agreements.

Finally, if Cairo decides to go ahead with bombing the dam, Egypt itself will become another unpredictable country. History shows us that when Egypt fights, its political compass often changes completely.

This is what happened after the 1973 war against Israel, when it changed its position from the Eastern to the Western camp.

However, if Cairo fights for its rights, it will definitely win. Its victory on the 1956 tripartite aggression was tantamount to cutting the tail of the British lion, the symbol of British Empire; Ethiopia would hardly prove less formidable.

Leave a Reply