INDEX

- Historical background

- The diplomatic dispute since 1945 to the Malvinas War.

- After the war: international organizations, diplomacy and territories of colonial remanence

- Conclusions

- Sources

Historical background

Discovered by Magellan in the sixteenth century, the Islas Malvinas (The Falkland Islands in Spanish) were a Spanish overseas territory, disputed by the United Kingdom in the late eighteenth century during its period of imperial expansion. Nevertheless, the Spanish domain and administration of the islands was effective until its abandonment in 1812. Argentina (the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata) had only in the last decade become an independent country. This is how in 1820, the authorities of the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata were able to acquire the abandoned islands as its property, a public act of assistance for navigators and fishermen of different nationalities (including British and American). The news was internationally known. During the process of recognition of the Argentine state by the United Kingdom, no claim was made on the archipelago, culminating in the signing of the Treaty of Friendship, Trade and Navigation of 1825 between both countries (Gustafson, 1988: 22).

The greatest exercise of Argentine sovereignty took place in 1829, when the government of Buenos Aires promulgated a decree to create a political-military ordination in Malvinas that continued the effective occupation of the islands– however, months later, a diplomatic protest of the United Kingdom would take place. The British then invaded the Malvinas Islands in 1833, expelling the authorities and the Argentine citizens who lived there. (Flachsland Coord., 2014, 25). The Argentine government began to intensify diplomatic claims before the British authorities, although without favourable answers.

In 1841, the United Kingdom appointed a governor and began to colonize the islands. However, the diplomatic situation surrounding the islands remained pending, as confirmed by the British Foreign Secretary in 1849, while Argentina continued its claims at different levels and without pause until the emergence of the UN (Gustafson, 1988). Within the framework of the United Nations, the Decolonization Committee in 1964 forced the United Kingdom into dialogue and to negotiate with Argentina. This was an uncomfortable situation for British and these negotiations did not come to any fruition, especially after the British began a policy diplomatic silence during the negotiations of 1980. This silence caused an escalation of tensions that would lead to the Falklands War of 1982 and subsequent British victory.

The diplomatic dispute since 1945 to the Falklands War.

The year the United Nations began in 1945, they started to generate international policies to decolonize the world. Within this framework, Argentina attested from the very beginning to its rights on the Malvinas Islands. One year later, the United Kingdom registered the Malvinas Islands on a list of Non-Self-Governing Territories required by United Nations Resolution 66/1 for the Right to Self-Determination of Peoples. The United Kingdom was the administrator of the archipelago and was obliged to present numerous reports to the United Nations, sparking Argentine reservation and indignation with each such presentation.

Subsequently, Resolution 1514 was adopted in 1960 with the beginning of decolonization processes of African nations, and a line of monitoring was created that was intended to govern the political principles that accompany the process of decolonization throughout the world. A year later, the UN decolonization committee was created whose mission was to study, supervise and guarantee the implementation of the measures of resolution 1514, also known as “declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples for eliminate colonialism in the world”. Shortly after, in 1964, the well-known “allegation of Ruda” took place, when Argentine diplomat José María Ruda explained the situation of the Malvinas to the United Nations, where the people who inhabited the islands had been forcibly expelled and supplanted, mostly, by inhabitants of the United Kingdom and its colonies (Filmus, 2014). This declaration would serve as a precedent for the Argentine claims regarding the Malvinas Islands in the UN.

When Ruda presented his arguments in 1965, the Malvinas Islands were recognized within resolution 1514 but with the particularity that, in this case, the territory would remain in the hands of a colonial power (Flachsland Coord., 2014, 29). This is how Resolution 2065 was generated, in which the United Nations declared an exceptional situation in the case of the Malvinas Islands. The resolution recognized these islands as a territory disputed only by Argentina and the United Kingdom and urged the parties to negotiate respecting the interests of the islanders.

Argentina and the United Kingdom began negotiations, but as they advanced they ended up paralyzed and without agreement. The Argentine government, since 1968, had been opening up the archipelago thanks to several proposals for agreements offered to the United Kingdom. These agreements, very favourable for the islanders and for the Anglo-Saxon metropolis that was going through a strong period of crisis, were relatively well received (Gustafson, 1988: 92). Some of the agreements were carried out with the participation of Argentine companies such as LADE (State Airlines) and Gas del Estado, which arrived in the islands thanks to the “Communications Agreement”, creating a link that aimed at the development of the islanders and its approach to the continent, the fluidity of fresh food resources that were scarce in the islands, the granting of a residence card for free circulation throughout Argentina, regular air service, as well as the offer to cooperate in matters of health, education, etc. (Public International Law, 2010). The United Kingdom tried to transform the negotiations into talks to avoid the problem of sovereignty, which is why, in the face of the permanent refusal to negotiate, Argentina denounced the British delaying strategy at the UN (CARI, 1992: 53).

British unwillingness to negotiate manifested to such an extent that in 1973 the United Nations, through Resolution 3161, expressed serious concern about the stalemate in the negotiations, while recognizing the will of the Argentine government to facilitate the process of decolonization, paying special consideration to the citizen of the islands, their welfare and interests (United Nations, 1973).

After the death of President Perón and the subsequent failure of the negotiations for shared sovereignty that were being carried out, the United Kingdom began to conduct studies and explorations of hydrocarbons around the Malvinas Islands.

The Argentine Republic issued its refusal of the explorations in a press release in response to the United Kingdom’s intentions, but despite the Argentine protest, the United Kingdom entrusted the exploration to Lord Shackleton in 1971, thus violating the agreements of mutual understanding that were being carried out for the transfer of sovereignty (Greño, 1977: 37).

Argentina interpreted this unilateral act as a provocation, raising its protest to the United Nations and finding backing by the OAS (Organization of American States). In 1976, finishing the studies carried out by the English mission, tensions increased, and Argentina withdrew its ambassador in London. A little later the Argentine Navy found a British research vessel that was sailing in Argentine territorial waters, which it ordered to stop, and, in the face of its refusal, it fired shots at its bow as a warning, which generated an immediate British protest before the Security Council of the United Nations (Maffeo, 2002: 6). This point signaled the end of the conversations that had taken place since 1968 and would not be resumed until shortly before the beginning of the war.

In 1981, the Military Junta, which had governed Argentina since 1976, toughened diplomatic demands to force the United Kingdom to comply with United Nations resolutions to sit down to negotiate, while the British refused to engage in a dialogue that included option of sovereignty for at least 25 years, stating that they supported the wishes of the island population. The island lobbies and the pressures of economic groups led the British authorities not to reach an agreement with Argentina, and this was how the negotiations ended paralyzed before an increasingly impatient Argentine government opted to use force to recover the islands.

It is important to note that 1983 marked 150 years of British occupation in the Falkland Islands and continued fruitless negotiations, especially the last 14 years in which Argentina had had enough patience and guarantees to negotiate with the United Kingdom.

After the Falklands War ended un Argentine defeat in 1982, Great Britain and Argentina cut relations, and it was not until 1990 during the “Treaty of Madrid” when both governments agreed to resume diplomacy. They agreed on a series of measures to promote economic cooperation and security in order to avoid an upcoming military event between the two countries, and Argentina undertook not to use force again for the claim of sovereignty; something seconded later in 1994 with the constitutional reform that, in spite of presenting the Malvinas cause as inalienable for the nation and the Argentine people, prohibited manu militariactions for its recovery. In general, the measures were clearly favourable to the United Kingdom in many aspects: on the one hand, security was assured in the island space and on the other, it created a business network before the new opening of a market in the largest Spanish-speaking country in South America which opened Argentina politically and economically to the liberal axis of the West.

After the war: international organizations, diplomacy and territories of colonial remanence

Resuming diplomatic relations in the following years, United Kingdom will achieve an important strategic position by taking some measures to ensure sovereignty, such as unilaterally extending the maritime miles of the archipelago’s administers, as well as a determined effort to grant permits to companies for the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons (Santoro, 1994).In 2004, the Constitution of the European Union was signed, where the Malvinas, South Georgia and South Sandwich were recognized as part of the United Kingdom, who manifested the argentinian reservation through its ambassador in Brussels.

Everything seemed favourable to consolidate the dominion of United Kingdom over the Falklands and its dependencies, but in 2009 Argentina presented to the UN the “External Limit of the Continental Platform” later achieving before the international community an important recognition of the extension of its maritime platform. In accordance with the rules of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLPC) and CONVEMAR (Convention of the United Nations on the Law of the Sea), Argentina managed to revitalize their claim since now both the Falklands and San Pedro Island (Original name of South Georgias, in Spanish)) and the South Sandwich Islands were within the Argentine submarine platform, something confirmed and ratified by the United Nations ruling in 2016 (the Guardian, 2016).

The island government soon transferred its discontent to London and shortly after, in 2013, they organized a plebiscite so that the inhabitants of the islands could decide which nation they wanted to belong to. The result of the vote marked a 99.8% desire to continue belonging to the United Kingdom (Dinatale, 2013). Despite this result, the United Nations does not recognize this plebiscite. It would not be the first time that the UN did not recognize an organized referendum for a territory administered by Great Britain. The case of Gibraltar (Spain), considered by the United Nations was in the same problematic line as Malvinas, received the same refusal before the two pronunciations of its inhabitants of 1967 and 2002 despite the fact that the population wanted to continue to belong to the United Kingdom, with results similar to the Malvinas plebiscite with a favourable opinion in more than 95% (Ruiz, 2017). The United Nations does not recognize the right of self-determination in these cases, since the population that mostly inhabits both Gibraltar and the Malvinas Islands was introduced by the metropolis and such referendums violate the UN Charter.

In turn, Argentina continues to denounce and obtain the support of the United Nations and other organizations such as the OAS and UNASUR (Union of South American Nations), because of the continued british militarization of the Islands and the South Atlantic, the execution of military exercises and the projection on Antarctica (Niebieskikwiat, 2017), violating the Madrid agreements that prohibited the militarization of the region, and the resolutions of the United Nations that continually urge negotiations. Likewise, one of the most serious accusations made by Argentina is the mobilization, on the British side, of nuclear weapons during the 1982 conflict and on several subsequent occasions (La Nacion, 2013), violating of the Treaty of Tlatelolco of 1969 and the UN Resolution 3472 on Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones signed by the international community in 1975 (United Nations, 1982), an accusation that Britain initially denied, although later it eventually recognized (Clarin.com, 2003).

From the government of Mauricio Macri relations with the United Kingdom relaxed opening a new change in the diplomatic attitude of Argentina where, in the face of apparent cordiality, both countries proceeded to identify the bodies of 123 unidentified argentinian soldiers who were killed on the islands, while greater cooperation regarding flights and fishing were established (Niebieskikwiat, 2018), as well as aid – not required by Argentina – in the search for the submarine ARA San Juan (de Carlos, 2017). This, however, does not substantially change the disposition of both countries.

The president himself affirmed not to renounce the rights and sovereignty over the Malvinas, while Great Britain, in turn, maintains its determination not to speak about sovereignty (Niebieskikwiat, 2018). On the official website of the government of The Falkland Islands is an open letter addressed to the United Nations expressing discontent and disillusionment with the new Argentinian president for continuing the claim and the Argentine blockade imposed on the islands (Falklands.gov.fk, 2017).

In 2016, Theresa May, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, made a statement to the Argentine authorities asking that the restrictions for the exploration of Falklands oil be lifted (Wintour y Goñi, 2016), and Argentine President Mauricio Macri gave in to this request to continue promoting dialogue between the parties, but without renouncing rights to the Malvinas Islands. This was described by many analysts and Argentine politicians as collaborationism (Diariopulse.com, 2016), and can also be interpreted as a serious strategic error, since the London complaint would not be made if it did not suffer the consequences of the blockade and the restrictions imposed by Argentina.

Conclusions

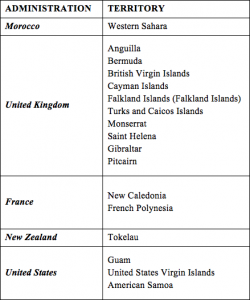

The United Kingdom is currently the country with the largest amount of overseas territories of colonial remanence, and yet this fact does not signify a problem for the UK’s foreign affairs. This can be explained, in part at least, due to their maintaining a favourable position internationally within organizations such as the United Nations Security Council, and thus managing to continuously circumvent the provisions regarding the Malvinas Islands. Apparently, the legality of international regulations and provisions can be discussed and unfulfilled depending on the country and the power it has, as in this case with the United Kingdom, which leads to questioning the effectiveness of the provisions of United Nations regarding the conflict of Malvinas Islands in general.

The conflict had not been solved after 17 years of dialogue and negotiations between London and Buenos Aires, eventually leading to the 1982 war. At present, due to the British refusal to negotiate, there is no sign of resolving the dispute through the dialogue, while the United Kingdom continues to militarily reinforce the Malvinas Islands in breach of the treaties signed with Argentina and the international provisions required by the UN, without consequences. Although Argentina has the resolutions of the United Nations in its favour and the diplomatic support of most countries in the world, this not enough to make the United Kingdom to sit down and negotiate.

Sources

CARI, (1992). Malvinas, Georgias y Sandwich del Sur. Perspectiva Histórico-Jurídica, Tomo I. H. Senado de la Nación

Clarin.com. (2003). “Malvinas: Londres admite que trajo armas nucleares al Atlántico Sur”. [online] Disponible en: https://www.clarin.com/ediciones-anteriores/malvinas-londres-admite-trajo-armas-nucleares-atlantico-sur_0_H1wxLl1l0Fe.html [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Derecho Internacional Público (2010). Declaración conjunta referente a la apertura de las comunicaciones entre las Islas Malvinas y el territorio continental argentino y su anexo – Derecho Internacional Público – www.dipublico.org. [online] Disponible en: https://www.dipublico.org/5900/declaracion-conjunta-referente-a-la-apertura-de-las-comunicaciones-entre-las-islas-malvinas-y-el-territorio-continental-argentino-y-su-anexo/ [Accessed 12 Apr. 2018].

de Carlos, C. (2017). Reino Unido se suma a la búsqueda del submarino argentino perdido. [online] ABC. Disponible en: http://www.abc.es/internacional/abci-reino-unido-suma-busqueda-submarino-argentino-perdido-201711181944_noticia.html [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Diariopulse.com (2016). Fuertes críticas a Macri por permitir al Reino Unido explotar el petróleo en Malvinas. [online] Disponible en: http://diariopulse.com/fuertes-criticas-a-macri-explotar-entega-petroleo-malvinas-al-reino-unido/23719 [Accessed 30 May. 2018].

Dinatale, M. (2013). Contundente triunfo del sí en el referéndum de las Malvinas. [online] La Nacion. Disponible en: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/1562319-contundente-triunfo-del-si-en-el-referendum-de-las-malvinas [Accessed 15 Apr. 2018].

Falklands.gov.fk. (2017). Address to The Special Committee on Decolonisation by The Honourable Ian Hansen, Member Of The Legislative Assembly of the Falkland Islands – 23RD JUNE 2017 | Falkland Islands Government. [online] Disponible en: https://www.falklands.gov.fk/address-to-the-special-committee-on-decolonisation-by-the-honourable-ian-hansen-member-of-the-legislative-assembly-of-the-falkland-islands-23rd-june-2017/ [Accessed 17 Apr. 2018].

Flachsland, C. Coord. (2014) Pensar Malvinas, Una selección de fuentes documentales, testimoniales, ficcionales y fotográficas para trabajar en el aula. Ministerio de Educación de la Nación Argentina.

Greño, J. E. (1977). “El “Informe Shackleton” sobre las Islas Malvinas”. Revista de Política InternacionalNº. 153. pp.:31-37.

Gustafson, Lowell (1988). The Sovereignty Dispute Over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. Oxford University Press.

La Nacion (2012). “Respaldo de 130 países a la Argentina por Malvinas”. [online] Disponible en: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/1467066-respaldo-de-130-paises-a-la-argentina-por-malvinas [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

La Nacion (2013). “La Argentina denunció en la ONU el refuerzo militar en las Malvinas”. [online] Available at: https://www.lanacion.com.ar/1558013-la-argentina-denuncio-en-la-onu-el-refuerzo-militar-en-las-malvinas [Accessed 4 May 2018].

Maffeo, A. J. (2002) “Negociaciones por Malvinas: continuidades y quiebres”. Relaciones Internacionales.nº 23. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. pp.:1-9.

Naciones Unidas, (1973), General Assembly. 3160 (XXVIII) Questions of the Falklands Islands (Malvinas). Disponible en: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/282/32/IMG/NR028232.pdf?OpenElement [Accessed 25 Apr. 2018]

Naciones Unidas (1982). A/RES/37/99. General and complete disarmament. [online] Disponible en: https://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/37/a37r099.htm [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Naciones Unidas (S.F.). Las Naciones Unidas y la descolonización. [online] Disponible en: https://www.un.org/es/decolonization/nonselfgovterritories.shtml#note3 [Accessed 17 Apr. 2018].

Niebieskikwiat, N. (2017). Malvinas: el Gobierno volvió a rechazar los ejercicios militares con misiles en el Atlántico Sur. [online] Clarin.com. Disponible en: https://www.clarin.com/politica/malvinas-gobierno-vuelve-rechazar-ejercicios-militares-misiles-islas_0_SJ2Yd3JAb.html [Accessed 14 Apr. 2018].

Niebieskikwiat, N. (2018). Gran Bretaña y la Argentina: avances y apuesta al diálogo por las Malvinas. [online] Clarin.com. Disponible en: https://www.clarin.com/politica/gran-bretana-argentina-avances-apuesta-dialogo-malvinas_0_r1zv5jkjG.html [Accessed 8 Apr. 2018].

Página/12. (2013). “Los argumentos para no dialogar”. [online] Disponible en: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/elpais/1-211180-2013-01-04.html [Accessed 17 Apr. 2018].

Santoro, D. (1994). “La Posición de Di Tella en la disputa por el petróleo en Malvinas”. En Revista de Relaciones InternacionalesNº.7, Instituto de Relaciones Internacionales, Universidad Nacional de la Plata. S. p. Disponible en: http://www.iri.edu.ar/revistas/revista_dvd/revistas/R7/R7EST04.html [Accessed 29 Apr. 2018]

the Guardian. (2016). “Falkland Islands lie in Argentinian waters, UN commission rules”. [online] Disponible en: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/mar/29/falkland-islands-argentina-waters-rules-un-commission [Accessed 15 Apr. 2018].

Wintour, P. y Goñi, U. (2016). Theresa May calls on Argentina to lift Falklands oil exploration restrictions. [online] the Guardian. Disponible en: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/aug/10/may-calls-on-argentina-to-lift-falklands-oil-exploration-restrictions [Accessed 18 Apr. 2018].

Leave a Reply