Stable Waters in a Polarized World

Stable Waters in a Polarized World

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

China and ASEAN have stood as a steadying force in a turbulent world where power is more fragmented, and rivalry grows. Despite regional tensions, mistrust, and the recent surge in militarization, a relationship between them has held firm, underpinned by no-nonsense economics, regular institutional engagement, and cooperation that purports to share benefit equitably across all sides. The “ship of friendship,” called upon by both sides in more recent times, is more than a diplomatic maxim—a robust and flexible system of regional cooperation that has implications for a polarizing world order.

It hasn’t been uneventful altogether in the affair. Maritime standoff in the South China Sea, political divergence of systems, and outside pressure tested trust. Yet, China and ASEAN have showed institutional strength in compartmentalizing tension and making higher-order ends meet. The negotiations for a Code of Conduct, imperfect and tortuous as they are, are a manifestation of such pragmatic determination—conflict management, not a chimera-like solution, is being sought. It is a diplomacy not of idealism, but strategic maturity on both sides.

Economically, the alliance is revolutionary. China has been ASEAN’s biggest trading partner for over a decade, and ASEAN has just become China’s biggest trading bloc, overtaking the European Union. The entry into force of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – the world’s largest free trade agreement – solidifies such interdependence but deeper, as an open market commitment by a greater number during a period when protectionism elsewhere rises. China’s moving through ASEAN-centric institutions rather than despite them constructs regional centrality and institutional complementarity. Infrastructure is also one area where the partnership has achieved progress beyond rhetoric.

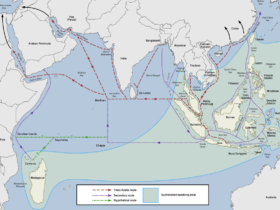

China–Laos Railway, Malaysian and Indonesian port modernization, and Thai and Cambodian industrial parks are expressions of physical connectivity. These, despite moments of controversy, answer ASEAN’s most fundamental development challenges: intra-regional trade costs, logistic shortcomings, and industrial upgrading. The urgent challenge is to make such connectivity sustainable, inclusive, and transparent. In all of this, China’s evolving Belt and Road initiative—with increased emphasis on “small and beautiful” projects—suggests a process of learning in sensitivity to public opinion. In fact, it is not a one-way partnership.

ASEAN has maintained this partnership on their own terms, ensuring their strategic independence and avoiding having to choose sides in great power competition in order to promote multilateralism. “ASEAN centrality” may be a non-physical concept, yet it carries substantial weight because it shapes discourse and helps to contain ambitions outside their realm. China has been able to adjust to this format because they rather prefer to interact through ASEAN-sponsored bodies such as the East Asia Summit and ASEAN Regional Forum than in equal bodies. Soft power is another vital element in this China-ASEAN relationship.

The people-to-people connections have been extended through exchange programs for students, cooperation in the media, cultural performances, and tourism promotion, all of which have ensured the maintenance of security issues in the background. The increasing popularity of Chinese and Southeast Asian films, music, and cuisines in the other market indicates a people-friendly familiarity that would be impossible to achieve through diplomacy at the top level. However, it is these people-friendly interactions that keep the “ship of friendship” afloat when the wind is blowing in the direction of trouble in the top-level relations between the two countries. However, the relationship is not devoid of some hitches, at least in the perspective of the ASEAN members, who still have some reservations regarding a certain dependence on Chinese solidarity, particularly in sensitive areas of strategic significance and infrastructure.

Debt sustainability concerns, environmental issues, and workers’ treatment are among those which remain contentious. Western powers however see the tilt towards Beijing by the region as cause for concern, stereotyping ASEAN hedging as drift rather than thoughtful pluralism. And so lies the long-term durability of our China–ASEAN relationship in eschewing such binarism. It is built not on alignment but on accommodation.

Conclusion

As fault lines around the globe solidify and faith in orthodox multilateralism dissipates, the China–ASEAN relationship offers a fascinating, if imperfect, paradigm of regional cooperation. It demonstrates that openness and engagement are compatible even amid competition; that connectivity and sovereignty need no longer be antithetical; and that cooperation doesn’t require homogeneity to flourish.

The “ship of friendship” is not headed for utopia—but it is sailing, under the impulse of the compass of common interest and the anchor of common respect. In a time of rancorous divisions and troubled waters, that alone is a journey worth taking.

Leave a Reply