Historic background and impressions from a visit.

Historic background and impressions from a visit.

By Orçun Göktürk, from Beijing / China

I spent 25 days in Taiwan. When I set out from Beijing on the morning of January 2nd and set foot in Taipei, the capital of this island of 22 million people, my mind was filled with the “imminent invasion” and “powder keg” scenarios served daily by Western media. However, the moment I stepped off the plane and blended into the streets, that orchestrated picture of tension was replaced by a completely different reality. As a PhD candidate in International Relations who has lived in Beijing since 2018, I saw firsthand how essential it is to read the Taiwan Strait issue not through transoceanic headlines, but from the streets of Taipei, Taoyuan, and Keelung.

The background of the island’s current status

To understand Taiwan’s current contradictory status, one must look back to 1949, the breaking point of the Chinese Civil War. Faced with the Communist Party of China (CPC) led by Mao Zedong, the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) forces led by Chiang Kai-shek—who could not hold their ground despite massive U.S. military and logistical support—sought refuge on the island with approximately 2 million soldiers and civilian supporters. Following this flight, an oppressive one-party dictatorship was established, lasting until 1986. The Western world often sweeps this reality under the rug, paradoxically packaging and marketing this authoritarian regime as the “bastion of democracy in Asia.”

During this period, Taiwan laid the foundations for the “miracle” that would turn it into a global technology giant, fueled by both U.S. aid and the incredible sacrifice and discipline of the island’s people. People I had the chance to talk to on the island, especially those over 60, specifically described how they used to work 18 hours a day. Consequently, they reaped the rewards as one of the “Four Asian Tigers” (Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, South Korea).

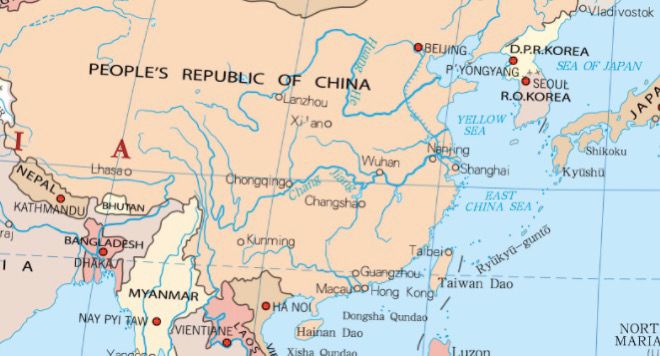

On the other hand, diplomatic history witnessed a major absurdity that lasted until 1971: with its population of only a few million, the “Republic of China” on the island held the authority to represent the 700-million-strong Mainland at the United Nations. This surreal picture was only shaken by the historic visit to Beijing in 1971, initiated by Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon’s “Ping-Pong Diplomacy.” Finally, in 1973, the Beijing-based People’s Republic of China reclaimed its legitimate seat at the UN, ending this diplomatic occupation and officially certifying the process that pushed Taiwan into the “gray area” of the international system. Today, the world—including the U.S. and, of course, the UN—recognizes Beijing’s “One China” policy. However, the uncertainty over Taiwan persists.

Political fission: The DPP and the politics of Taiwanese identity

At the center of Taiwan’s current political fault line lies the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), founded in 1986. Born as a reaction to the KMT’s martial law and “One China” claim, the DPP shifted the island’s politics from the axis of “unification with the mainland” to a liberal yet staunchly “Taiwanese Nationalist” axis. In contrast to the KMT’s traditional line of considering itself the legitimate representative of China, the DPP built itself on an ideological ground representing Taiwan’s cultural and political rupture from the mainland.

The DPP has very strong ties with the U.S., particularly with globalist circles. House Speaker Pelosi’s 2022 visit to the island, which brought China and the U.S. to the brink of conflict, was conducted as a message to Beijing because of this bond. However, the DPP has recently been in a difficult position; they lost major cities and their parliamentary majority. Nevertheless, they managed to win the general elections (even though their vote share dropped significantly) and successfully elected Lai Ching-te as “President.”

During my visit, I had extensive meetings with executives from both the ruling DPP and the main opposition KMT. I visited the headquarters of both parties, though I could not enter the DPP building because it was late. I even had dinner at the famous Raohe Night Market in Taipei with party officials who appear political adversaries but do not abandon dialogue.

Orchestrated fear? Genuine tranquility?

It bears repeating: the most striking element during my time in Taiwan was the tranquility of life on the island. If you relied on reports from Washington-based think tanks, you would think sirens were about to go off in the skies of Taipei at any moment. Yet, the pulse of the Taiwanese people beats quite differently.

The island has a GDP of nearly $900 billion, with a per capita income around $38,000–$39,000. The people are economically comfortable. Their largest trading partner is the People’s Republic of China. For the vast majority of Taiwanese, the People’s Republic is not a “monster” waiting to attack at any moment; it is the old Motherland where thousands of investments, family ties, and a shared history flow. However, on the other hand, the CPC is largely viewed as the biggest “threat.” In this sense, the U.S. has succeeded in separating the Mainland and the Island in the public consciousness.

Taiwan is governed by the DPP. Most media outlets are structured to repeat exactly what the West and the U.S. say—and even more. For this reason, there is a reckless pro-Westernism prevalent, to the point of hanging an Israeli flag on the “Taipei 101” building after the October 7 events…

A significant portion of the public understands that China’s military exercises are not aimed at them, but are a direct response to provocative U.S. moves in the region. Nevertheless, they are certainly uncomfortable with the drills.

The statistics encountered here are quite striking: research shows that only a tiny minority of 2-3% of the population wants “immediate unification” or “immediate independence.” The remaining massive 95% want to “maintain the status quo.” If this research by the American firm PEW is taken as a basis, there is a visible social resistance against the island being dragged into a conflict zone by major powers. However, people mostly feel closer to Japan than to CCP-led China. Let us look at the reasons why…

Why the affection for Japan?

To understand the sense of belonging of the Taiwanese people today, one must look at the tragic rupture of the island in 1895. With the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the Qing Dynasty handed over Formosa (Taiwan’s name at the time) to the Japanese Empire like a “dowry.” This 50-year Japanese colonial period, which lasted until 1945, left a different legacy in Taiwan compared to other examples in Asia. Japan’s desire to turn the island into a “model colony” laid the foundations for a comprehensive education system, railway networks, modern agricultural techniques, mining modernization, and industrial infrastructure. The Japanese-inspired discipline and architectural texture felt today on the streets of Taipei are seen as coded in the collective memory as an “orderly” past compared to the inhumane practices of Japanese imperialism on the mainland.

However, the real driving force of this proximity lies in ideological consent rather than material infrastructure. The island was previously colonized by Spain (North Taiwan) and the Netherlands (South Taiwan) in the 17th century. The arrival of first the Zheng and then the Qing Dynasty from the Mainland occurred during this period. All dark traces of Western exploitation have been almost erased from the public mind through the ideological tools of Western hegemony.

Naturally, if Taiwanese people today feel closer to Japan or the U.S. than to CPC-led China, the main reason is the cultural hegemony established by the Western-centered “democracy” narrative. Defining their lives largely through these liberal democratic values, the island’s people view their relations with Japan and Western countries as more than just a partnership of interest—it is a “relationship of the heart” and a “defense of a shared lifestyle.” By using this mechanism of consent, the U.S. and the West have arguably succeeded in turning historical ties on the island into a security wall and an ideological barricade against China. The decline of U.S. hegemony and the post-liberal international order are not yet fully felt on the island.

Western hegemony constructs a crisis narrative over Taiwan to consolidate its declining power. However, this process of “manufacturing consent” is supported by information pollution and censorship mechanisms. It is remarkable that while the Israeli flag was projected onto Taipei 101, a large part of the public was left unaware of global developments, such as the human tragedy in Gaza, due to intense disinformation.

Despite this, the pragmatic and threatening language of the Trump administration, such as “if we are protecting you, you have to pay for it,” brings about a deep questioning, even if it does not sow seeds of anti-Americanism. People are beginning to realize the cost and risk behind the U.S. promise of “protecting democracy.” I can say that Trump’s recent threats toward Europe and the beginning of the Atlantic alliance’s fragmentation have started to create awareness in some, if not most, of the people I spoke with.

The organic ties between the two sides

For me, crossing from Beijing to Taipei meant traveling between two geographies that are connected by invisible but unbreakable ropes, yet contain just as many differences. Despite the major ideological differences, I communicated with the Taiwanese using the Chinese I learned in Beijing and tried to listen to and understand them.

On the other hand, major ties with the Chinese Mainland continue on an economic basis. The massive progress in semiconductor and chip technology, which lies beneath Taiwan’s economic miracle, ensures integration with the mainland today. The success of the state-led mixed system has made Taiwan a technology hub for Asia, not an object of conflict. The liberal fairy tale is actually falsified in the specific case of Taiwan.

However, this prosperity is threatened today by provocations coming from across the ocean. The “Democracy-Authoritarianism” dichotomy imposed by the West does not actually find a full equivalent in Taiwan’s historical and cultural fabric. While protecting their economic gains, some Taiwanese want to discuss peaceful coexistence formulas with China without foreign intervention.

In whose hands is the future?

Will Taiwan be a “pawn” of imperialist strategies, or will it be the “keystone” of peaceful coexistence as a symbol of the non-combative nature and politeness of the island’s people? During my visit, the ruling DPP approved a new arms deal of nearly $12 billion from America and announced they would make $40 billion in arms purchases this year. This is exactly where the real provocation that threatens peace on the island and risks the “One China” principle comes from.

My 25-day field observation and interviews with hundreds of Taiwanese shows that the solution lies not in weapons bought as if paying “tribute” to the U.S., but in the region’s own natural balance.

In conclusion, the people of Taiwan do not want war; they are weary of provocations and do not intend to let their future be spent at the geopolitical gambling table of the transoceanic power. Historical dynamics and social common-sense herald that the island will be a center of peaceful unification and regional stability rather than a center of conflict. These calm and peaceful people are almost the same as those I saw in Beijing or any city on the Chinese Mainland—with their language, food and drink culture, and much more. Even without pro-U.S. leaders, I must say that the people have the sagacity to silence the noise of provocations.

Leave a Reply