From Outsider to Architect?

From Outsider to Architect?

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

When China initially made overtures to rejoin the world trade system in 1986, it was as an economic unknown. Its role in international trade was slight, its industry nascent, and its institutions only beginning the transition from a closed command economy to one tentatively open to the forces of markets. The long marathon race that began with that application to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) culminated in its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001—a milestone moment that transformed China and, in doing so, the world. Twenty years ago, that script was being turned on its head, as the United States—the former guarantor of free markets—was retreating into a tariff-led, unilateralist direction. It is China now, though, that appears to be assuming the mantle of defender—and maybe even reformer—of the world trading order.

The parallel between the two trajectories is striking. The United States under Donald Trump, and now more broadly even in broader bipartisan rhetoric, has grown increasingly disillusioned with multilateralism and openly defiant towards trade liberalization. Tariffs are now not even considered instruments of bargaining anymore, but instruments of punishment and of leverage. Washington’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), its paralysis in WTO dispute mechanisms, and its use of national security as a fig leaf for protectionism have all heralded a new strategy: economic nationalism is no longer a minority position in American trade policy—it is its core.

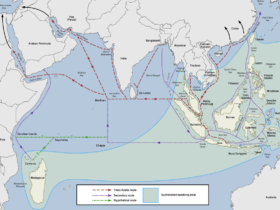

China, in contrast, is embracing the very institutions in which it once fought to gain entry. It has become the largest trading partner to over 120 countries, launched the Belt and Road Initiative to connect itself into global supply chains, and become a leader in the WTO, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and other trade frameworks. Though critics are right to point out China’s mercantilism, industrial subsidies, and state capitalist system, its public policy has been unified: China is a champion of globalization, an enemy of tariffs, and a protector of open markets.

Not mere rhetorical posturing. Beijing recognizes that the moment is a fleeting geopolitical window. As the U.S. appears to be giving up its lead in global trade regulation, China is in a position to be a calming presence—particularly to Global South countries, several of which are disenchanted by the conditionalities and asymmetries of Western-led trade regimes. Through its promotion of reforms that center on development, technology transfer, and balanced access, China is able to attract emerging economies not only by way of bilateral agreements, but through normative leadership.

Besides that, China’s diplomatic approach to trade is in transition. Whereas earlier initiatives were all about conformity with WTO accession, China is today an active participant in rule-shaping where the U.S. is not. Its aspirations for Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) accession, its advocacy for digital trade norms through regional and bilateral alignments, and its standard-setting role through the RCEP all reflect a shift from reactive to proactive engagement.

But it is not contradiction-free. China is still both a proponent and a critic of the world trade order. It lectures on openness with sheltered investment regulations behind the scenes. It laments protectionism but empowers strategic industrial policy. These contradictions fuel doubts if China wants to uphold the rules or remake them in its own image.

But perhaps more pressing is whether China is the best steward of globalization, rather than whether it is the last one left to keep the system from imploding. The WTO, weakened already by paralysis in its appeals body and growing obsolescence in e-commerce and climate trade, needs to be overhauled. If the U.S. decides not to lead—and worse, actively disavows multilateralism—then the maintenance of a rules-based order will depend on others stepping into the void. Europe, ASEAN, and parts of the Global South are holding their breath, waiting to see whether Beijing’s words are accompanied by institutional commitments.

China as a guardian of globalization is the vision that conflicts with much of the West and especially those who had previously foreseen economic unification as the way to open up China inwards. However, history cannot have tidy ideological curves. With or without the leadership of the Americans, multilateralism of trade will never cease. It will shift location, adapt, and perhaps reinvent itself as forces that speak to new center of gravities. China’s rise from trade rule-taker to future rule-shaper is not an eleventh-hour transformation, but the inevitable product of decades of engagement, negotiating, and economic evolution.

Conclusion

China’s trajectory through the world trading system—would-be WTO member in 1986, go-to leader in 2024—tracks with its greater transition from periphery to center of the world stage. While America withdraws, tariffs as instrument, and endeavors to undo multilateral norms, Beijing is uniquely placed to push for a trade order that once it was necessary to fit in to be included in.

It doesn’t mean China is building a perfect copy of the old model. It doesn’t at all mean that Beijing is selfless. But in a time when economic disintegration threatens to become blocs with the adversary, Beijing’s moves toward investing in institutions, outlining a vision of trade, and taking seriously emerging markets offer a second option to implode.

For a world economy that is still dependent on cross-border trade in goods, information, and capital, the question now isn’t if China will reign supreme, but if anyone else will even care. If America is bent on destroying the house it built, China can quite happily be the one to take over the job of rebuilding. The result won’t be a rehashing of history—but it will be the sole building to be left standing.

Leave a Reply