For the wider Muslim world, the Saudi-Emirati estrangement poses a dilemma but also an opportunity.

For the wider Muslim world, the Saudi-Emirati estrangement poses a dilemma but also an opportunity.

By Dure Akram, from Lahore / Pakistan

Saudi warplanes bombarding a Yemeni port city held by Emirati-aligned fighters – a scenario unthinkable a few years ago – became reality as 2025 drew to a close.

On December 30, Saudi Arabia accused the United Arab Emirates of arming separatists in Yemen and launched airstrikes on the southern city of Mukalla to stop an alleged weapons shipment to the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC). UAE rejected this claim even as it announced the withdrawal of its remaining forces from Yemen.

Within days, Saudi-supported forces drove the separatists out of key provinces, according to Yemeni military officials and local security sources in Hadramawt and al-Mahra. Saudi-backed fighters have reclaimed much of the territory the STC had seized in eastern and southern Yemen, notably in Hadramawt and al-Mahra.

Yemen’s internationally recognized government expelled STC leader Aidarous al-Zubaidi from its ruling council, and he fled the country on January 7, 2026. Saudi officials alleged the UAE facilitated Zubaidi’s escape via Somaliland and onward to a UAE destination, an accusation the UAE has not publicly acknowledged.

Some STC members announced a split or disbandment amid internal divisions and strategic setbacks; others in the movement say the organization persists. The factional situation is fluid.

A Saudi-Emirati coalition that once jointly fought Yemen’s Houthis was now effectively at war with itself, bringing a dramatic end to years of UAE influence in the south and fracturing the alliance against the Houthis.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE initially entered Yemen’s civil war in 2015 on the same side, vowing to restore the Yemeni government ousted by Houthi rebels. But from the outset, their priorities diverged. Riyadh saw the Iran-aligned Houthis as an existential threat on its border, while Abu Dhabi’s main concern was crushing Islamist factions (like the Islah party) in southern Yemen.

For a time, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) and Abu Dhabi’s Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ) worked in lockstep – the older MBZ was even regarded as a mentor to the young Saudi prince. That unity was short-lived.

The UAE began a drawdown from frontline combat roles in Yemen by 2019, increasingly supporting local proxies such as the STC.

By the early 2020s, cracks had widened into a chasm: Abu Dhabi was carving out spheres of influence via local proxies, and Riyadh was growing resentful at bearing the brunt of an unwinnable war against the Houthis alone.

Beyond Yemen, the two Gulf powers found themselves at odds on multiple fronts. Saudi leaders were shocked when the UAE appeared lukewarm on reconciling with Qatar after the 2017 embargo– a blockade both countries had initially enforced in tandem. Economic competition then sharpened the rivalry.

In 2021, their officials openly sparred over OPEC+ oil production levels. That same year, Saudi Arabia rolled out policies seemingly aimed at undercutting the UAE’s status as the Gulf’s business hub – from allegedly ending tax perks for goods transiting UAE free zones to mandating that any company seeking Saudi government contracts move its regional headquarters to the Kingdom.

MBS’s government even launched a new national airline to challenge Emirates and Etihad, as part of an aggressive Vision 2030 drive to make Riyadh a global commercial centre.

At the heart of the rift are two conflicting outlooks for the Middle East. Saudi Arabia, fixated on attracting foreign investment, has pursued a strategy of de-risking the region – projecting stability and tamping down conflicts. This meant mending fences with rivals (Qatar, Turkey, even Iran) and seeking a lull in wars.

The UAE, meanwhile, has shown a higher tolerance for risk, wielding outsized influence by backing non-state actors and taking bold bets. From Libya’s battlefields to Sudan’s coup plotters, Abu Dhabi has been accused of funding and arming proxy forces in pursuit of its interests. In Yemen, that meant supporting the STC’s separatist ambitions; in Libya, supporting General Haftar’s militia; in Sudan, reportedly arming the Rapid Support Forces. Such adventures ran directly counter to Riyadh’s emphasis on order and its own security red lines.

Indeed, when STC fighters—armed and emboldened by Emirati aid—surged into Yemen’s Hadramawt and Mahra provinces in early December 2025, it crossed a Saudi red line. Those two provinces share long borders with Saudi Arabia and Oman, and their takeover by separatists was seen in Riyadh as an intolerable provocation during a Gulf leaders’ summit. The furious Saudi reaction in Yemen was thus a loud and clear message.

Diplomacy has so far prevented a total rupture. Neither side wants a repeat of the Gulf’s 2017 schism, when Saudi Arabia and the UAE led a coalition to isolate Qatar. There are tentative off-ramps. Abu Dhabi quietly withdrew its remaining military personnel from Yemen after the Saudi intervention. Both governments have also tried to compartmentalize their feud.

In public, they maintained a united front on other issues, even issuing a joint statement urging an end to the Gaza war and conducting scheduled GCC military drills together. These gestures suggest Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are keen to avoid a full-blown GCC breakup. Yet the underlying divergence in their trajectories is undeniable.

The Israeli-Palestinian arena has become another theatre of divergence. After the Abraham Accords in 2020, the UAE forged ahead with full normalization with Israel, decoupling its relations from the Palestinian issue. For a while, Saudi Arabia seemed ready to follow that path under U.S. encouragement. All that changed on October 7, 2023, when Hamas’s brutal attack and Israel’s devastating war in Gaza upended Saudi calculations. Arab public outrage over Gaza’s destruction made it impossible for Riyadh to continue downplaying Palestinian rights. MBS swiftly hit pause on any Israel deal and reverted to the Kingdom’s traditional stance: no peace with Israel without a credible path to Palestinian statehood. The UAE, by contrast, maintained its ties with Israel through the Gaza war – condemning the carnage in public statements, but pointedly positioning itself as a key Arab interlocutor with Israel in managing Gaza’s aftermath.

When Israel expanded its strikes beyond Gaza, it alarmed Riyadh about an unrestrained Israel operating with impunity across the region. In this context, Emirati alignment with Israel started to look like part of a deeply threatening bloc from the Saudi vantage point. Saudi media proxies lashed out, condemning the UAE as “anti-Islamic” and “pro-Israel” in an unusual war of words between allies.

The ripple effects have reached even the Red Sea and South Asia. Somalia, traditionally cordial to Abu Dhabi, abruptly annulled all its agreements with the UAE in January – including port deals and security pacts – after accusing it of “hostile actions” on Somali soil. Mogadishu’s breaking point was the discovery that the UAE had covertly spirited the fugitive STC leader (al-Zubaidi) through Somalia’s Somaliland region after he fled Yemen. To Somalia’s federal government, which opposes Somaliland’s secession, this was the last straw.

In a striking move, Somalia’s ministers praised Saudi Arabia’s role in stabilizing Yemen and explicitly linked their action to “a broader regional convergence” with Riyadh’s more assertive stance against Abu Dhabi’s meddling.

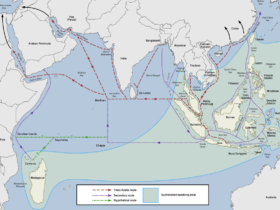

Perhaps the most revealing development is the role of Israel and India in this emerging divide. In late 2025, Israel became the first country to formally recognize the breakaway Republic of Somaliland – a move facilitated by Abu Dhabi, according to regional officials. For the UAE and Israel, cultivating an ally on the Horn of Africa shores (and a port in Somaliland’s Berbera) aligns with their strategic interest in dominating the Red Sea trade corridor. Saudi Arabia, in turn, has doubled down on backing Somalia’s territorial unity and forged its own security cooperation with countries like Djibouti and Eritrea to counter the UAE’s presence. Observers note that a new Red Sea Cold War could be brewing: on one side, an Israeli-Emirati axis seeking footholds from Somaliland to Sudan; on the other, a Saudi-led coalition rallying African and Arab support to check those ambitions. Major Asian powers are also intuitively gravitating into this split.

India – which has deep ties with both Israel and the UAE – appears sympathetic to the emerging Abu Dhabi/Jerusalem bloc, even as it maintains cordial relations with Riyadh. By contrast, Pakistan – historically aligned with Saudi Arabia – has thrown in its lot firmly with Riyadh’s camp. In October 2023, Islamabad and Riyadh inked a new strategic partnership, and Pakistani officials have signaled support for Saudi positions on issues like Palestine. The alignment makes sense. Pakistan’s public and parliament are staunchly pro-Palestinian, and any Saudi stance distancing itself from Israel resonates strongly in Islamabad.

Meanwhile, the UAE’s burgeoning defense and economic links with India (and its neutrality toward New Delhi’s policies in Kashmir) have quietly irked Pakistan. The net result is a geopolitical realignment that cuts through the Muslim world and beyond.

For countries like Pakistan and Turkey, the Saudi–Emirati rift poses a delicate balancing act. Both have strong ties with Riyadh and Abu Dhabi and would prefer not to choose between them. Pakistan in particular has vivid memories of the last time it was asked to take sides: in 2015, Saudi Arabia expected Pakistani troops to join the Yemen war, but Pakistan’s parliament voted for neutrality – a shock rebuke that prompted an angry UAE minister to warn Islamabad it would pay a “heavy price” for its “ambiguous stand.”

Indeed, the UAE accused Pakistan of siding with Iran by staying out of Yemen and hinted at retribution despite the Gulf states’ billions in past aid. Pakistan weathered that storm by emphasizing its continued support for Saudi Arabia’s territorial defense while politely declining to fight in Yemen. In hindsight, that decision may have spared Pakistan from entanglement in a disastrous war. Now, Islamabad faces another moment of truth. It counts both Saudi Arabia and the UAE as crucial economic partners – over 77% of Pakistan’s overseas workers went to those two countries in 2022, sending home billions in remittances that keep Pakistan’s economy afloat. The Emirati royals also have longstanding business investments in Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia has been a lender of last resort for Islamabad during financial crises. Little wonder, then, that Pakistan’s official line is one of studied neutrality in the Saudi–UAE spat, coupled with calls for Muslim unity. Pakistani diplomats privately hope the feud will blow over; publicly, they offer to mediate and “play a proactive diplomatic role” rather than take sides – the same stance Pakistan articulated during the Yemen conflict.

Beneath the surface, however, Pakistan’s strategic tilt is clear. In the emerging divide, its natural alignment lies with Riyadh. Saudi Arabia remains the guardian of Mecca and Medina and the leader of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) – positions that carry immense weight in Pakistani domestic politics. By contrast, the UAE’s recent embrace of Israel puts it at odds with Pakistani public opinion, which is overwhelmingly pro-Palestine and hostile to any normalization with Israel. There is even speculation that Saudi Arabia’s more assertive posture against the UAE could open doors for Pakistan: for instance, Riyadh might funnel more economic projects Pakistan’s way (to spite the UAE) or coordinate with Pakistan on security initiatives in the Horn of Africa and Indian Ocean, where Islamabad has naval interests.

Still, Pakistan will tread carefully – it cannot afford a rupture with Abu Dhabi, which hosts over a million Pakistani expatriates and, in 2021, provided a $2 billion loan during Pakistan’s cash crunch.

Turkey finds itself in a similarly nuanced position. President Erdoğan has spent the past two years mending fences with both Mohammed bin Salman and Mohammed bin Zayed after a decade of acrimony. Turkey’s economy, struggling in recent years, welcomed Emirati and Saudi investment as Erdoğan normalized relations – trade and currency swap deals were signed, and Gulf money started flowing into Turkey’s markets. Yet Turkey’s affinities tilt toward the same axis as Pakistan’s: Erdoğan has been one of the loudest voices in the Muslim world decrying Israel’s actions in Gaza, aligning him rhetorically with Saudi Arabia’s post-October 7 stance.

Moreover, Ankara shares Riyadh’s interest in stabilizing regions like Syria and Libya through political settlements, whereas the UAE’s encouragement of separatist or militia agendas in those countries runs against Turkish interests.

Ankara might even offer itself as a mediator, leveraging its contacts with both Gulf leaders.

The Saudi-UAE rift is far more than a personal spat between two ambitious princes – it represents a fundamental shift in Middle Eastern geopolitics. The two wealthiest Arab states that once marched in lockstep are now pursuing divergent and at times opposing agendas. This split comes at a volatile moment, with an Iran–Israel shadow war simmering, multiple Arab states in turmoil, and great-power influence in flux. If Riyadh and Abu Dhabi cannot reconcile their visions, the consequences could be profound. We may see dueling blocs start to solidify: one orbiting around Saudi Arabia’s quest for a stable, multipolar region (with partners like Qatar, Egypt, Turkey, and Pakistan); another coalescing around the UAE’s more revisionist, security-driven outlook (drawing in Israel, and tacitly India, and hawkish elements in Washington). Smaller Gulf states are watching warily. Oman and Kuwait, both allergic to regional quarrels, are quietly urging mediation. Even Qatar – no friend to Abu Dhabi – is cautious, remembering how intra-GCC feuds can spiral. It is telling that the GCC as an institution has been largely mute during this crisis, a sign of how internal divisions have paralyzed collective action.

For the wider Muslim world, the Saudi-Emirati estrangement poses a dilemma but also an opportunity. On one hand, a fracture among wealthy Gulf benefactors could further weaken institutions like the OIC at a time when a united voice is badly needed on issues such as the plight of Gaza or Islamophobic policies in various countries. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia’s break from the UAE’s regional strategy might restore a degree of credibility to the idea of Muslim solidarity – particularly on the Palestine question.

Likewise, countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, which were uneasy with the Abraham Accords’ sidelining of Palestinians, may take heart that the Arab world’s preeminent power refuses to normalize at any cost.

The conversation within the Muslim world may increasingly turn to tough questions: How to prevent external powers from exploiting divisions – as colonizers once did – to weaken Muslim unity? And critically, how can regional heavyweights resolve disputes without exporting them into poorer nations’ conflicts, as happened in Yemen, Libya, and Sudan?

Leave a Reply