The Abdülhamid era stands as the most “splendid” and consequential phase of Sino-Ottoman relations, representing both the zenith of Ottoman global Islamic diplomacy and the practical limits of Pan-Islamism as an instrument of imperial outreach.

The Abdülhamid era stands as the most “splendid” and consequential phase of Sino-Ottoman relations, representing both the zenith of Ottoman global Islamic diplomacy and the practical limits of Pan-Islamism as an instrument of imperial outreach.

By Dr. Halim Gençoğlu

Sino-Ottoman relations, while often perceived as marginal due to geographical distance and the absence of sustained formal diplomacy, in fact rest upon a much deeper historical background that extends to the early interactions between the Turkic–Islamic world and China through the Silk Road, Muslim trade networks, and religious exchanges dating back to the medieval period. Although the Ottoman Empire did not establish continuous bilateral diplomatic relations with China in the classical sense prior to the nineteenth century, Chinese Muslim communities increasingly came to recognize the Ottoman sultan-caliph as a symbolic and spiritual authority, particularly through pilgrimage routes that positioned Istanbul as a key intermediary center. The most prominent, visible, and institutionally ambitious phase of Ottoman–Chinese relations emerged during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876–1909), when Pan-Islamism was articulated as a central pillar of Ottoman foreign policy and the caliphate was mobilized as a global unifying instrument aimed at strengthening transregional Muslim solidarity in the face of Western imperial expansion. Within this framework, the Ottoman state initiated direct engagements with Chinese Muslim populations by dispatching advisory delegations—most notably the Nasihat Delegation of 1901—and by establishing educational institutions such as the Pekin Hamidiye University in 1908, which sought to disseminate Ottoman-style Islamic education, reinforce loyalty to the caliphate, and counteract Western missionary influence. These initiatives elevated Ottoman–Chinese relations to their historical peak by transforming them from indirect and symbolic contacts into tangible diplomatic, cultural, and educational interactions, thereby leaving a lasting imprint on Chinese Muslim communities, particularly the Hui population. However, the long-term sustainability of these relations was undermined by structural limitations, including geographical remoteness, colonial intervention, the collapse of the Ottoman state, and the subsequent political transformations in China, culminating in the interruption of religious and educational exchanges after 1949. Consequently, the Abdülhamid era stands as the most “splendid” and consequential phase of Sino-Ottoman relations, representing both the zenith of Ottoman global Islamic diplomacy and the practical limits of Pan-Islamism as an instrument of imperial outreach.

The Life of Mustafa Şükrü Efendi

Mustafa Şükrü Efendi (1851–1924), known as a madrasa scholar, a member of the Meclis-i Tetkîkât-ı Şer’iyye (Council for the Examination of Shar‘i Matters), and a lecturer in the Huzur Dersleri (Imperial Presence Lectures), served in a religious capacity on the “Nasihat Delegation” sent to China during the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II. This delegation was formed during the Boxer Rebellion with the aim of offering caliphal counsel to Chinese Muslims and represents a reflection of Ottoman diplomacy’s Pan-Islamist policies. While Bülent Ecevit is known as one of the most influential figures in Turkish political history, his grandfather Mustafa Şükrü Efendi adds further depth to his biography. This article examines the biography of Mustafa Şükrü Efendi and the historical context of the delegation sent to China.

Mustafa Şükrü also served as a mukarrir (lecturer) in the Huzur Dersleri, thereby contributing to the religious education of the sultan. Şükrü Efendi’s intellectual legacy resonated in the cultural formation of his grandson Bülent Ecevit, who proudly referred in family stories to his grandfather’s nickname, “the Chinese Hodja.”

Sultan Abdülhamid’s China Diplomacy

Sultan Abdülhamid II (1876–1909) transformed the caliphate into an international instrument through his Pan-Islamist policies. Within this framework, he undertook diplomatic initiatives aimed at Muslim communities in the Far East. The Boxer Rebellion, which erupted in 1900, emerged as a nationalist and anti-Western movement in China, resisting Western colonialism. The Boxers, organized as a sect known as Yihequan, carried out attacks against Christian missionaries and foreigners, which led to the occupation of Beijing by eight Western powers (Germany, Russia, Britain, France, the United States, Japan, Italy, and Austria-Hungary). At the request of German Emperor Wilhelm II, Abdülhamid decided to send a delegation to warn Chinese Muslims against participating in the uprising. This “Nasihat Delegation” aimed to prevent bloodshed by invoking the spiritual authority of the caliphate and to increase Ottoman influence. The delegation departed from Istanbul on 18 April 1901, with its expenses covered by the Germans.

The delegation consisted of military, scholarly, and diplomatic elements. It was headed by Mirliva (Brigadier General) Hasan Enver Pasha (the grandfather of Nazım Hikmet). Other members included Kolağası Yaver Ömer Nazım Bey (the brother-in-law of Enver Pasha), the interpreter Viçinço Kinyoli, Qadi Hacı Tahir Efendi, and attendants. Its mission was to convey the following advice to Chinese Muslims: observance of shar‘i rights, loyalty to the Chinese Emperor, and avoidance of rebellion against Western powers. Indeed, the delegation arrived in Shanghai on 3 June 1901, but since the uprising had already been suppressed, it achieved only limited impact. Meetings were held with German Field Marshal Waldersee, and the issue of confiscated Muslim cemeteries was resolved. The delegation stayed in China for 21 days and returned via Russia. In their reports, they noted that the influence of the caliphate in the Far East was limited.

The Mission and Journey of the Delegation

The official mission of the Nasihat Delegation was to convey the greetings of Abdülhamid II and to advise Chinese Muslims not to participate in rebellion. This aimed to prevent bloodshed by utilizing the spiritual authority of the caliphate and to enhance Ottoman influence. The delegation departed aboard a Russian ship, transferred to a German vessel in Suez, stopped in Colombo and Singapore, and reached China on a Japanese steamer. On the return journey, they traveled via Japan, Korea, Vladivostok, and Siberia, arriving in Odessa and returning to Istanbul on 5 August 1901. The journey lasted four months, and each delegation member was paid an allowance of 500 Ottoman gold coins.

The reports draw attention to the presence of Ottoman subjects in Singapore (Greeks, Armenians, Jews) and to the Muslim population, which constituted one-third of the total population. There were seven mosques, and the Turkish flag was raised during Friday prayers. Mirliva Hasan Enver (Nazım Hikmet’s grandfather) proposed the establishment of a permanent consulate in the region and met with the Turkish honorary consul, Abdülhamid Efendi of Baghdad. This demonstrates the diplomatic dimension of the report, as the delegation examined not only religious counsel but also commercial and administrative networks. The delegation remained in China for 21 days, conducted mosque visits and discussion gatherings, and Mustafa Şükrü Efendi delivered shar‘i counsel, earning the nickname “the Chinese Hodja.” The reports emphasized that Chinese Muslims showed great respect toward the delegation and loyalty to the caliphate, though the actual influence remained limited.

Enver Pasha’s report highlighted the problem of the absence of a Turkish consulate along the maritime route between Istanbul and China, stating that “the lack of Turkish consulates at major centers along the entire sea route between Istanbul and China constitutes a negative situation.” While criticizing the Ottoman diplomatic vacuum in the Far East, the report proposed innovative initiatives. Waldersee’s distant attitude toward the delegation was criticized, and it was noted that Western powers were uncomfortable with the delegation’s role as a “messenger of peace.” The reports reveal the practical limits of Pan-Islamism. Although the caliphal message was conveyed and efforts were made to pacify uprisings, tangible impact remained limited. Despite noting that Chinese Muslims harbored deep sentiments toward the Ottomans and that sermons were delivered in Abdülhamid’s name, geographical distance and Western occupations posed significant obstacles.

The Role of Mustafa Şükrü Efendi

Mustafa Şükrü Efendi was selected as a müderris representing the learned class (ilmiye) of the delegation. His duty was to deliver shar‘i counsel and reinforce the religious authority of the caliphate. As a teacher at the Beyazıt Madrasa, he organized mosque visits and discussion sessions with Chinese Muslims. Upon his return, he acquired the nickname “the Chinese Hodja,” which became embedded in family tradition. The allowance document shows that Şükrü Efendi received 500 Ottoman gold coins. His activities functioned as propaganda and mediation efforts aimed at calming the uprising and strengthening the bond of the caliphate.

Pan-Islamism, as an ideology that positioned the caliphate as a global unifying force, constituted the foundation of Ottoman foreign policy. Within this framework, intelligence agents and delegations were sent from Africa to India and as far as China. This visit increased Chinese Muslims’ loyalty to the Ottoman Empire; the name of Abdülhamid began to be mentioned in sermons, and pilgrims started stopping in Istanbul on their way to the hajj.

In 1902, Muhammad Ali—known as a Fatih Mosque müderris and an intelligence agent from Batumi—was sent, and in 1905 Süleyman Şükrü Bey was dispatched to China to continue contacts. In 1906, the Chinese Muslim leader Imam Wang Kuan (Abdurrahman), on his return from the pilgrimage, stopped in Istanbul, met with Abdülhamid II, and was influenced by the Ottoman education system. The Sultan gifted Wang approximately 1,000 Islamic books and supported the idea of establishing a university in Beijing. In this context, documents located in the Ottoman Archives of the Prime Ministry (BOA) (Y.PRK.HR. 29/69, İ.HUS. 88/3, etc.) confirm that the project was planned step by step.

Purpose and Diplomatic Role

The main purpose of the university was to strengthen loyalty to the caliphate by providing Islamic education to Chinese Muslims, to conduct propaganda against Western missionary activity, and to concretize Islamic unity. Sultan Abdülhamid II’s Pan-Islamist vision encouraged spiritual resistance against colonial powers; the university represented the educational dimension of this policy. Based on mosque schools in China, the Ottoman model was adapted, and sacred sites such as the Niujie Mosque were turned into gathering points for Muslims. Diplomatically, it elevated Ottoman–Chinese relations to their peak, ensured that sermons were delivered in the name of Abdülhamid, and increased pilgrimage traffic.

Construction began in 1907 and was carried out in an area adjacent to the Niujie Mosque, within its courtyard. The structure had a modest architectural design consisting of a main building and three classrooms. The design, bearing Islamic elements, was symbolized by the Ottoman flag flying at the entrance. Completed within a year with the support of Chinese Muslims, the building rose through public effort despite colonial obstacles. The opening took place with prayers in 1908. Although the participation of officials from the Beijing Ministry of Education had been planned, the opening was delayed due to a snowstorm. The ceremony was held with Arabic prayers translated into Chinese, creating joy and excitement among the participants. The opening, reported on 5 March 1908 in the newspaper Tercüman-ı Hakikat, was described in the Ottoman press as “a major event.”

Education was initiated by teachers sent from the Ottoman Empire. The main instructors were: Ahmet Ramiz Efendi, a teacher from the Fatih Mosque; Hafız Ali Rızâ Efendi; Hafız Tayyib Efendi; and Hafız Hasan Efendi from Bursa. A monthly salary of 3,000 kuruş was allocated to these teachers, and Hafız Ali Rızâ and Hasan Efendi provided instruction for one year. After the departure of the teachers, Chinese Muslims (under the leadership of Imam Wang) took over the administration. The students consisted of Chinese Muslim children of all ages, and approximately 120 students were enrolled within one year. The curriculum was based on the Ottoman madrasa model. Arabic, Qur’anic exegesis (tafsir), hadith, Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), and Qur’an memorization (hifz) were emphasized. Enriched with modern elements, instruction highlighted preaching, moral exhortation, and sermon delivery. The books were supplied as gifts from Sultan Abdülhamid, and the education was designed to reinforce Islamic unity. The university faced problems such as obstruction by colonial states (Britain, France, Russia), logistical difficulties, and the early departure of teachers. The repercussions of the Boxer Rebellion and Western missionary activity undermined Pan-Islamist efforts, while financial insufficiencies also limited activities. After the departure of the teachers, the institution was reduced to the level of a primary school.

Closure of the Institution and Its Aftermath

With the Mao Zedong revolution in 1949, Arabic and religious education were banned, and the university was completely closed. While the building was abandoned due to financial reasons, Ottoman motifs were erased, although Islamic architectural features were preserved. One classroom is currently used for religious courses for youth, while another has been converted into the Niujie Mosque history museum. As the most distant educational initiative of the Ottoman Empire in the Far East, Peking Hamidiye University symbolizes the global legacy of the caliphate. The building was restored during the 2008 Beijing Olympics and was declared a “historical monument” by the Chinese government. Today, the empty classrooms—used during festivals and Friday prayers when the mosque overflows—serve as reminders of the former Ottoman–Chinese ties.

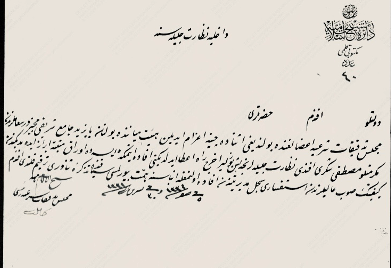

(Ottoman Archives, Y..PRK.MŞ.. H-30-12-1319)

Conclusion

The wise figure of the Uyghur Turks, Mahmud al-Kashgari, stated in his work Dîvânu Lugâti’t-Türk: “A knowledgeable person is like one who can see among the blind.” The Ottoman State, almost with this very mission, sought to spread light throughout the Islamic world as far as China. The Boxer Rebellion, which erupted in China in 1900, went down in history as a nationalist resistance against Western imperialism and led to the occupation of Beijing by eight Western powers. In line with Sultan Abdülhamid Khan’s Pan-Islamist policies, and at the request of German Emperor Wilhelm II, the Ottoman State sent a “Nasihat Delegation” with the aim of offering caliphal counsel to approximately 50–55 million Chinese Muslims. The delegation departed from Istanbul on 18 April 1901 and was headed by Mirliva (Brigadier General) Hasan Enver Pasha, the grandfather of the poet Nazım Hikmet. Among its members were Kolağası Ömer Nazım Bey (secretary), the interpreter Viçinço Kinyoli, Qadi Hacı Tahir Efendi, and the religious scholar Mustafa Şükrü Efendi, who was the grandfather of Bülent Ecevit. The delegation arrived in Shanghai on 3 June 1901 on a journey whose expenses were covered by the Germans; however, since the uprising had already been suppressed, its mission remained limited.

The reports are found in academic studies, contemporary correspondence, and especially in the Ottoman Archives of the Prime Ministry, and their full texts are preserved in archival documents (HR.SYS and Y.A.HUS). Mustafa Şükrü Efendi, as one of the last representatives of the Ottoman ulema, embodied the caliphate’s effort at global outreach within the China Nasihat Delegation. Peking Hamidiye University (Dârü’l-Ulûmi’l-Hamidiyye, or Hui Jiao Shi Fan Xue Tang in Chinese sources) was an educational institution founded in 1908 in Beijing, the capital of China, during the late period of the Ottoman State, as a symbol of Sultan Abdülhamid’s Pan-Islamist policies. Located in the courtyard of the Niujie Mosque, this madrasa aimed to reinforce the spiritual and cultural influence of the Ottoman caliphate over Muslim communities in the Far East and focused on the education of Chinese Muslims (the Hui people). As a concrete reflection of Abdülhamid’s vision, Hamidiye University pushed the boundaries of Pan-Islamism; it left a lasting bond of affection among Chinese Muslims in which Ottoman diplomacy was intertwined with education, and it enriched the historical Turkish–Chinese relationship.

References

Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (BOA), HR.SYS ve Y.A.HUS Koleksiyonları.

Aykurt, Çetin. “Bir Büyük Düşünce: Pekin Hamidiyye Üniversitesi.” Tarih İncelemeleri Dergisi, Cilt 28, Sayı 1, 2013, ss. 37-50.

“Sultan Abdülhamid’in Çin’e Vurduğu Mühür: Pekin Hamidiye Üniversitesi.” İttifak Gazetesi, 24 Ocak 2024.

“Pekin’de Bir Osmanlı Mührü: Hamidiye Üniversitesi.” Bi’ Dünya Haber, 3 Eylül 2019.

“A Century-Old Ottoman Legacy in China.” Muslim Population, Erişim: 2025.

Çelik, Mehmet. “Panislamizm’in Etki Alanı Çerçevesinde Çin’e Gönderilen Nasihat Heyeti.” Uluslararası Tarih ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, Sayı 14, 2015.

Mutlu, C. “Boksör Ayaklanması ve Sultan Abdülhamit’in Nasihat Heyeti.” Türk Dünyası Araştırmaları Dergisi, 123 (2019): 313-330.

Toros, Taha. “Çin’e Giden Nasihat Heyeti.” Yakın Tarihimiz, Sayı 19, Nisan 1982.

Eraslan, Cezmi. II. Abdülhamid ve İslam Birliği. Ötüken Yayınları, 1992.

Çetin, Mahmut. Çinli Hoca’nın Torunu Ecevit. Emre Yayınları, 2006.

Çelik, M. “Panislamizm’in Etki Alanı Çerçevesinde Çin’e Gönderilen Nasihat Heyeti.” İSAM, 2015.

“Boksör Ayaklanması ve Sultan Abdülhamid’in Nasihat Heyeti.” Tarih Dergisi, 2019.

Leave a Reply