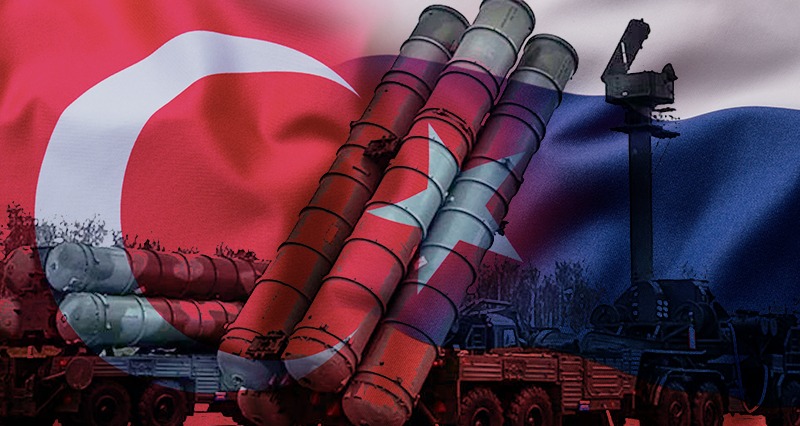

For Türkiye, the S-400s have become something far greater than air defense assets. They are a measure of strategic resolve.

For Türkiye, the S-400s have become something far greater than air defense assets. They are a measure of strategic resolve.

By Yıldıran Acar, Political Scientist

Türkiye’s acquisition of the Russian-made S-400 air defense system has long ceased to be a technical or even military issue. In Russian media and expert circles, it is now treated as a strategic resilience test—one that measures not only Ankara’s resilience under Western pressure, but also the credibility of Türkiye’s long-claimed strategic autonomy.

From Moscow’s perspective, the renewed American push to “resolve” the S-400 issue is neither surprising nor accidental. What has changed is the intensity and tone of the pressure. Russian analysts note that Washington is no longer content with symbolic compromises or temporary freezes. The demand is increasingly framed in absolute terms: Türkiye must not merely refrain from using the S-400s but must cease to possess them altogether.

This framing is widely interpreted by Russian experts as a deliberate attempt to force Ankara into a binary choice. As Vladimir Avatkov, head of the Middle East and Post-Soviet East Department at the Russian Academy of Sciences, argues, Türkiye is once again being pushed to a geopolitical crossroads. Yet unlike earlier periods—when Ankara functioned as a predictable extension of NATO’s southern flank—today’s Türkiye is far less controllable and far more assertive. For Washington, this assertiveness is precisely the problem.

In Russian strategic discourse, the S-400 crisis is often presented as part of a broader American effort to discipline allies rather than accommodate them. The logic is simple: a Türkiye capable of independent military procurement, diversified partnerships, and autonomous regional policy undermines the coherence of the U.S.-led security architecture. As several Russian commentators bluntly put it, “An independent Türkiye is more dangerous to Washington than an unfriendly one.”

Russian experts also consistently reject the argument that NATO membership alone makes the S-400 purchase illegitimate. Alina Sbitneva of the Russian Academy of Sciences points out that neither NATO treaties nor international law prohibit member states from acquiring non-NATO weapon systems. Moreover, Türkiye is not alone in this practice. Greece’s possession of Russian air defense assets is frequently cited—not as a rhetorical trick, but as evidence of selective enforcement driven by politics rather than principles.

The key distinction, according to Russian analysts, lies in intent. Greece integrated Russian systems quietly and without challenging the broader Western security consensus. Türkiye, by contrast, used the S-400 deal to signal dissatisfaction with Western conditionality and to assert its right to sovereign defense decisions. In Moscow’s reading, Ankara crossed an invisible line—not by buying Russian weapons, but by refusing to treat the purchase as an anomaly requiring apology.

Perhaps the most sensitive issue in Russian expert debates is the potential transfer of the S-400 systems to a third country. Here, the tone shifts from analytical to openly cautionary. Any scenario involving the relocation of Turkish S-400s—particularly to Ukraine—is viewed as a fundamental breach of trust. Russian analysts describe this as a “point of no return,” one that would force Moscow to reassess not only military cooperation with Türkiye, but the entire political logic underpinning bilateral relations.

This concern is often framed in stark contrast. Russian commentators emphasize that Moscow fulfilled its contractual obligations fully and without political preconditions. By comparison, they argue, Western offers to Türkiye remain largely hypothetical—conditional promises tied to shifting political moods in Washington and congressional approval processes beyond Ankara’s control. From this angle, the S-400 issue becomes less about hardware and more about credibility.

At the same time, Russian experts are careful not to exaggerate Türkiye’s dependence on Western platforms. The absence of F-35s, they note, has not paralyzed the Turkish Air Force. On the contrary, Ankara has accelerated alternative paths: cooperation with European suppliers, expansion of UAV capabilities, and the development of the KAAN fifth-generation fighter. These efforts are widely interpreted in Moscow as evidence that Türkiye is hedging against long-term Western unreliability rather than desperately seeking reentry into the American defense ecosystem.

Russian military analysts also tend to downplay Western narratives surrounding the S-400’s performance in Ukraine when discussing Türkiye. Claims about vulnerabilities to drones or precision strikes are acknowledged, but they are rarely treated as decisive. The real question, in Moscow’s view, is political endurance. Can Türkiye sustain the costs—economic, diplomatic, and strategic—of defying U.S. demands? And if it cannot, how far will it go to mitigate those costs without crossing Moscow’s red lines?

Ultimately, Russian expert opinion converges on a sober conclusion: the S-400 issue is not a rupture, but it is a warning. Moscow does not expect Türkiye to abandon its balancing strategy overnight. Yet there is a growing sense that ambiguity has limits. If Ankara chooses symbolic concessions, Russia will watch patiently. If it chooses irreversible alignment, Russia will respond accordingly.

For Türkiye, the S-400s have become something far greater than air defense assets. They are a measure of strategic resolve—an indicator of how much autonomy Ankara can preserve in an increasingly polarized international system. And in Moscow, that measure is being calculated with quiet precision.

Leave a Reply