A Fracture Within the Atlantic Front

A Fracture Within the Atlantic Front

By Orçun Göktürk, PhD Candidate at UIBE in Beijing / China

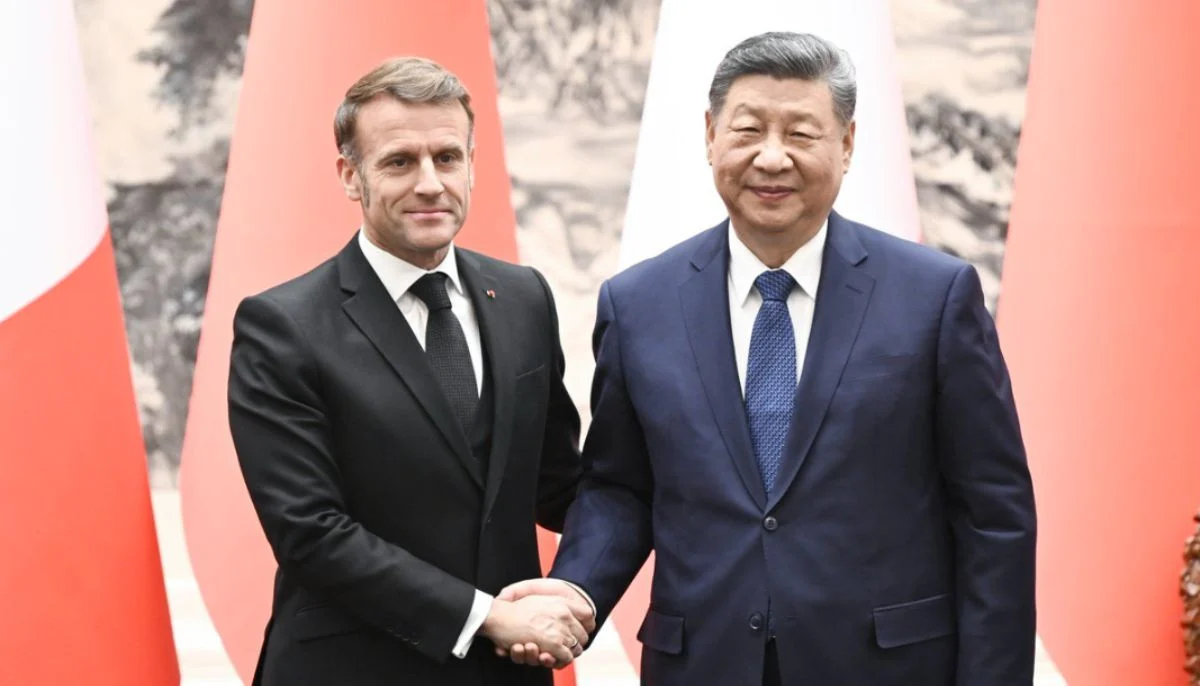

French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit to China coincided with a period of rising China–Japan tensions and a short-lived “ceasefire” in China–US relations following the Busan talks. It also unfolded in an atmosphere where both Beijing’s strategy of “flexible diplomacy” toward Europe and Europe’s squeezed position between Washington and Beijing became increasingly visible.

Chinese media framed the visit under the headline “Support for Europe’s search for strategic autonomy.” Western media, however, took a more cautious tone, describing Macron’s attempt to remain committed to globalization while deepening economic ties with China as “a diplomatic walk full of contradictions.” In truth, the discrepancy between Beijing and Paris on globalization is not substantial. Beijing is reintroducing to the world the neoliberal “globalization” narrative of the EU–Atlantic alliance, but on its own terms. The real contradiction, therefore, lies in Macron and EU leadership’s insistence on maintaining this framework.

During Macron’s three-day visit, Beijing’s central rhetorical message was clear: the Atlantic bloc need not be seen as monolithic; the political cracks between Europe and the United States can be widened. For this reason, Chinese diplomacy tends to position Macron as a counterweight to the Biden administration. The most symbolic moment of the visit came when Chinese President Xi Jinping told Macron: “In this multipolar world order, we need to stand on the right side of history.” This phrase encapsulates the strategic message China has long conveyed to Europe:

- Move away from Washington’s Cold War mindset and show the courage to chart your own path in a multipolar order;

- Position yourselves within the new distribution of global power.

Xi’s statement serves both as a warning and an invitation: Abandon the EU’s tendency to demonize China—particularly on issues like Ukraine—and do not sacrifice areas of economic integration to political tensions.

Macron’s China Dilemma

Macron’s situation is highly complex:

On one side stands a Europe deeply dependent on the U.S. for security, embedded within NATO and aligned (at least with the globalist camp) with Washington. On the other side stands France’s historical project of asserting Europe’s independence. Macron’s rhetorical defense of “strategic autonomy” contradicts the Atlantic line that has consolidated after the outbreak of the Ukraine war.

Thus, while Beijing sees Macron’s visit as an opportunity to pull Europe further away from Washington, in French domestic politics it has triggered criticism that Paris is “distancing itself from the U.S.” Yet economic interests are decisive: France needs the Chinese market. From Airbus to luxury brands, Chinese demand is of vital importance.

What further deepens Macron’s contradiction is the newly released U.S. National Defense Strategy, in which Washington signals a shift away from acting as a globally omnipresent hegemon in favor of a more selective and pragmatic doctrine centered on homeland security + regional hegemony + deterrence. This is also accompanied by a declaration of stepping back from acting as Europe’s “global police force.”

Was Gramsci Right? The Cultural Influence of Liberal Hegemony in China

Another striking scene throughout Macron’s visit was the enthusiastic reception he received from the Chinese public—particularly the youth. Everywhere he appeared, crowds greeted him almost like a Hollywood celebrity, which is not merely a diplomatic footnote but a sign of a deeper cultural, liberal shift accumulating in China.

Having lived in China since 2018, my observation is this: Among the younger generations, there is a near-romantic admiration for the West and an increasingly strong attachment to liberal concepts such as so-called “democracy” and “freedom” rhetoric. Even though platforms like Netflix, Instagram, and X (Twitter) are banned, the “liberal virus” has already penetrated society. For, as Gramsci argued, hegemonic ideas are not only imposed externally—they can also reproduce themselves from within society. Cultural dominance finds ways to bypass economic or political barriers.

Mao summarized this dynamic long ago when he asked:

“Why is it that some people can no longer see the contradictions within socialist society? Is the old bourgeoisie not still present? Is the massive petty-bourgeois class not before everyone’s eyes? Are there not still large numbers of intellectuals whose transformation is incomplete? Are the effects of petty production, corruption, bribery, and the black market not everywhere?” (《毛主席重要指示(1975—1976)》,中共中央文件,1976年3月印发for Eng: Important Instructions of Chairman Mao (1975–1976), Central Committee Document, March 1976)

Despite the CPC’s ideological tightening today, the strengthening of Western-centric aspirations among young people is therefore notable. A visible erosion has occurred in society’s self-confidence—particularly in comparison to the West. The marginalization of revolutionary values within the cultural hierarchy enables a figure like Macron to be approached with near-prophetic fascination.

This indicates that within China’s cultural struggle, liberal hegemony has become an increasingly powerful magnet. In other words, Gramsci may indeed have been right: an ideology shapes society primarily through consent-building, not coercion. Liberalism’s presence in China is precisely the product of such consent.

Economy, Diplomacy, the Ukraine Question

Ultimately, Macron’s visit is significant as part of Beijing’s strategy to partially separate Europe from the Atlantic bloc. Yet the cultural scenes that emerged during the visit point to another tension: while China strengthens its political and ideological challenge to the West, the West remains the primary source of attraction for China’s youth. Thus, Macron’s trip is not only a geopolitical event, but also a test that reveals the ongoing struggle over cultural hegemony in China.

Finally, Macron did not come to Beijing to impose anything regarding Ukraine. The deeper issue is that Europe, without the United States, resembles a headless rooster—unsure of what to do. This is most clearly seen in the trade figures: in 2024, France ran a 54-billion-dollar trade deficit with China. Unless Macron—or any other European leader—reverses neoliberal policies and reconnects with production, Europe will remain unable to pursue a symmetrical economic agenda with China.

Leave a Reply