Stalemate by Design, Escalation by Drift

Stalemate by Design, Escalation by Drift

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

There are fewer great power hotspots so long-lasting, so complicated, and so politically obstinate as the South China Sea. It has been a measure of great power competition, an experiment in naval convention, and a melting pot of nationalist anxieties for ten years. The 2025 picture is one of stalemate, more than solution, still less spectacular de-escalation. Rather, the dynamics that have ever defined the tensions of the region persist—and, in a way, are only becoming more challenging. The disagreements, if they are, are less numbed than perpetuating: what has been and is will remain so, and likely even more so.

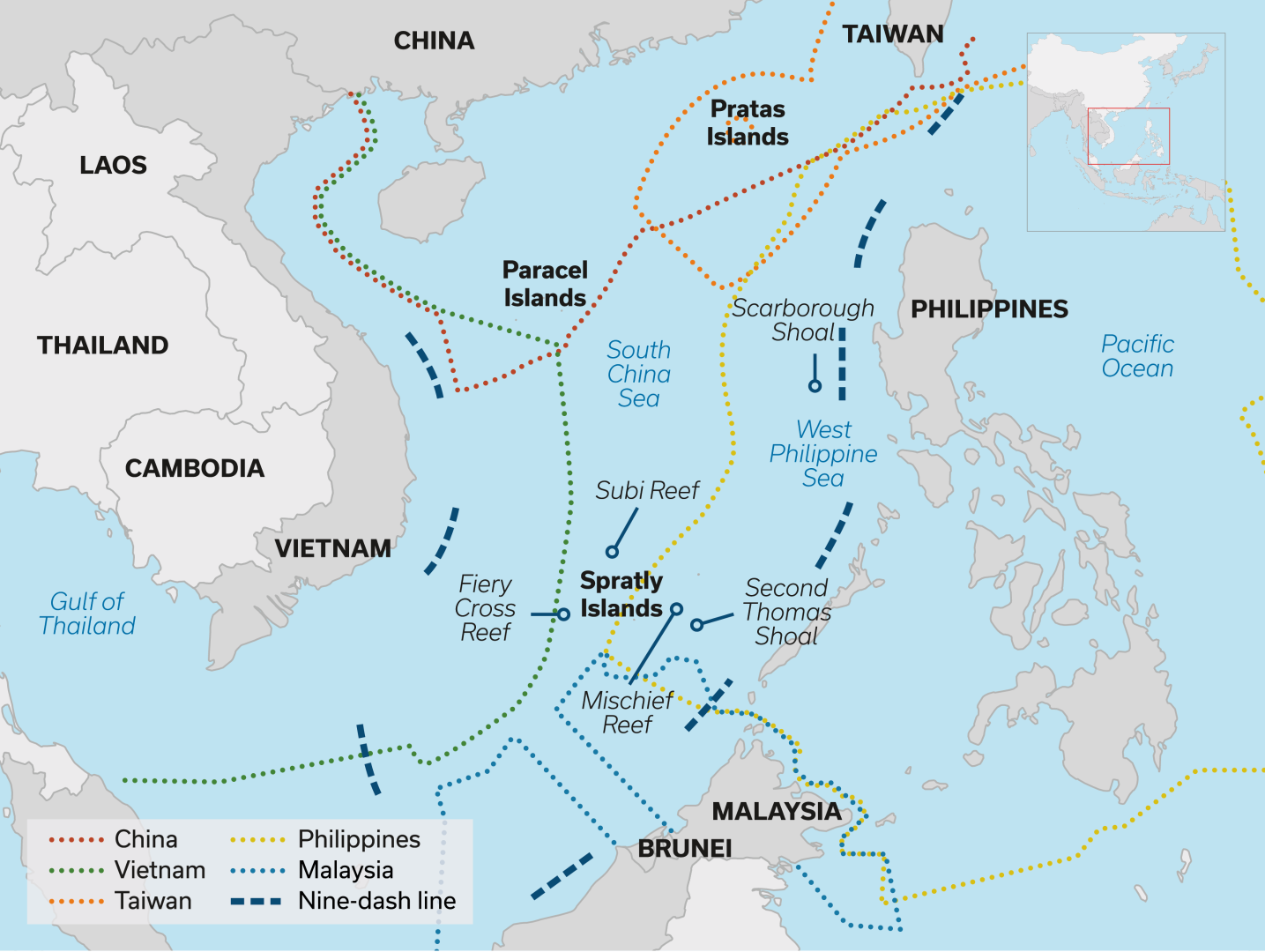

The path is now well-worn. China has expansive historical claims under the “nine-dash line” with increasing assertive naval presence, militarization of artificial islands, and diplomatic intransigence. Southeast Asian claimant states—most symbolically Vietnam and the Philippines—respond with diplomatic démarche, legalistic argumentation, and occasional assertive maritime maneuvering. At the same time, foreign powers such as the United States, Japan, and Australia carry out freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), offer rhetorical support to ASEAN claimants, and enhance defense ties—all in the interest of preserving a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” This is a vicious cycle of provocation and reaction with no breakthrough but much symbolism and danger.

China’s calculation does not alter. By exerting a persistent presence—coast guard patrol operations, science ships, paramilitary fishing fleets—Beijing achieves two objectives. Firstly, it acquires de facto control of features in dispute, whether they possess or lack legal status in international law. Secondly, it conditions its presence so that it is politically and diplomatically costly to other powers to challenge it. This is not just coercion; it is habituation. With every repeated encounter, every withheld fishing permit, every halted oil exploration vessel, another step toward gaining a status quo in China’s favor to complement Beijing’s strategic patience and regional supremacy.

The administration of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has been more proactive than that of his father, invoking once again the 2016 arbitral ruling pronouncing China’s expansive claims as null and void and actively resisting Chinese incursions around Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal. The temerity of the Philippines has not shaken Beijing, though. Instead, it has triggered more assertive Chinese coast guard actions—water cannon use, blocking, and in-your-face eyeing. All the diplomatic support the Philippines receives from Washington and other countries is significant, but it makes no physical contribution to the naval balance of power in the ocean. China’s gray zone behavior remains tuned to just below the level of armed conflict, in a chronic state of low-grade annoyance hard to deflect and virtually impossible to resolve.

ASEAN is nonetheless at a disadvantage, meantime. The much-anticipated Code of Conduct (COC) negotiations with China, touted as a diplomatic cure-all, is still at an amorphous drift. It is incremental, secretive, and will not provide binding steps or enforcement mechanisms. Large ASEAN members are seriously divided in their approach—some desire economic cooperation with China over security, while others, notably Vietnam and the Philippines, desire stronger regional and international support. Inconsistency at home renders ASEAN consensus a pipe dream, undermining the group’s hopes of setting the agenda or dictating the outcome in the South China Sea.

American positions have grown louder, but maybe not necessarily more lucid. FONOPs continue, allied assistance increases, and senior leaders reaffirm treaty commitments regularly. But unadjusted deterrence can have its limits, though. Short of a more grandiose diplomatic strategy—of engaging China short of military signaling and supporting regional states in building credible naval capability—sole American presence will not alter the strategic balance. Indeed, militarization of regional diplomacy could make dependence deeper without strengthening resilience.

The most alarming trend may be the creeping normalization of risk. Incidents of near misses, aggressive patrols, and incursions into the border area are no longer regarded as escalatory acts but as normal events. On one level, the risk is not only exhaustion but miscalculation. In a world so permeated by suspicion and tactical bluffing, one misstep—a collision, a skirmish that gets out of control—can lead to an unintended escalation. And as compared to recent decades, when crisis management channels were more stable, this geopolitical reality of today provides fewer cushions and greater resistance. Conclusion

The future of the South China Sea in 2025 is grim. The crisis is far from over, and the trend lines are one of continued entrenchment and not strategic adjustment. China’s aggressiveness is not going away, ASEAN diplomatic unity is not yet stable, and outside powers keep cranking up presence without intention. The result is an uneasy, unstable status quo that sustains rather than reduces tension.

To overcome this inertia will require more than posturing right across the reactive order. It will require a new diplomatic imagination—not deterrence to dialogue, but national interest to regional architecture. ASEAN must ask itself whether its current toolkit is sufficient to address one of the region’s most offensive security challenges. China must consider the long-term reputational cost of coercive action. And external powers need to realize that presence without purpose has its limits.

Unless this rebalancing occurs at the regional level, then the South China Sea will remain what it has for so long: not a war theater, but an area of strategic atrophy. The threat isn’t so much that things will deteriorate—but that we won’t appreciate it until they do.

Leave a Reply