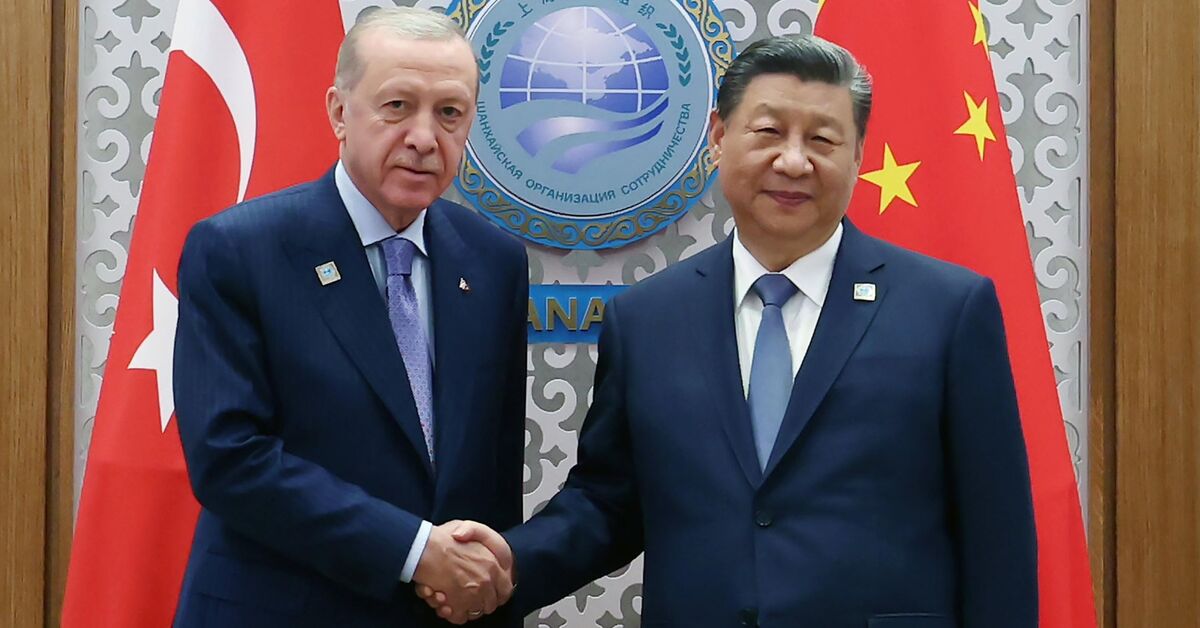

The Turkish President will attend the upcoming SCO summit, Chinese authorities declared.

The Turkish President will attend the upcoming SCO summit, Chinese authorities declared.

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

Türkiye has been the crossroads of civilizations for a number of decades, a unique geopolitical standing that bridges Europe and Asia, NATO and the Middle East, Islam and secularism, democracy and strategic pragmatism. Yet Türkiye’s own position within the world system has been constrained by its participation in Western alliances, above all NATO and the European political space. Recent developments throughout the world have however begun to destroy these traditional formats and to reveal new possibilities of strategic direction. Among these, Türkiye’s growing involvement with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) can perhaps be most significant. More than a diplomatic flirtation, Türkiye’s courtship of the SCO represents a pragmatic realignment that will have revolutionary ramifications for Ankara and enriching payoff for the organization itself.

Initially conceived as a regional security entente among China, Russia, and the Central Asian republics, the SCO has since transformed into an inclusive forum for security, economic collaboration, counterterrorism, and regional integration. Its expansion to include India and Pakistan—and growing relevance in Eurasia—prove that it is not a club of regional powers anymore, but a rising geopolitical bloc with aspirations to create a new multipolar world. That is why Türkiye’s geopolitical role can no longer be imagined going unnoticed. As a G20 economy, a military power, an Islamic world diplomatic heavyweight, and a regional gateway to Europe and the Middle East, Türkiye stands well-placed to elevate the global stature of the SCO.

Membership in the SCO is a long-awaited Turkish foreign policy diversification. The failed and protracted accession talks with the state and the European Union laid bare weaknesses of Western-led diplomacy. Meanwhile, rising tensions within NATO—over Türkiye’s unilateral military intervention in Syria, its purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system, and its assertive energy explorations in the Eastern Mediterranean—generated a strategic vacuum that Ankara is keen to fill with new alignments. The SCO provides a forum in which Türkiye is able to follow its national interest free from ideological bias, and in which its regional agendas—whether in Central Asia, the Caucasus, or the Turkic world—can be institutionalized.

Aside from that, the SCO aligns with Türkiye’s emerging Eurasianist vision. Over the past decade, Turkish policymakers and intellectuals began to turn east, not out of any anger at the West but because they understand that the world’s gravity is shifting. Whether in oil pipelines, cyber networks, defense alliances, or currency swap deals, the future is multipolar. The SCO provides not only a forum for economic collaboration with great powers like China, Russia, and India but also a forum for collective response to regional security concerns like extremism, separatism, and transnational crime—concerns that have direct implications for Turkish national interests.

Turkish membership in the SCO would also help bridge cultural and civilizational distances between the founding membership of the organization and the broader Islamic societies. As the Muslim majority’s secular state, Türkiye possesses a hybrid identity that can be employed to mediate Eurasian governance modes and Islamic worldviews. This has particular applicability to the case of China’s Xinjiang sensitivities and broader frames of reference for Islam’s role in modern statecraft. Turkish membership can be leveraged to enact a soft balancing strategy—ideologizing polarization, entrenching the organization’s legitimacy in Muslim-majority states.

Turkish membership would represent a worthwhile strategic gain for the SCO. It would expose the organization to the Eastern Mediterranean, grant it direct influence over NATO’s only Muslim majority member, and secure for it a much-coveted partner in the administration of energy security issues, refugee movements, and infrastructure integration. Türkiye’s defense industry, logistical role, and diplomatic role in multilateral institutions—from the UN to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation—can help turn the SCO into an institution of global consequence of its current regional mechanism. When institutions like NATO and the G7 are being seen as elitist and ideologically doctrinaire, the SCO’s pragmatism and eclecticism are its source of strength. Its home naturally is Türkiye.

The skeptics would prefer to believe that Türkiye’s NATO membership and decades-long Western orientation render SCO integration impossible or conflictual. This is predicated, however, on a closed bloc model of international alignments no longer operative in the world we are experiencing. Geopolitics is no longer closed blocs but overlapping spheres of influence. India and Pakistan, SCO members, are also close to the West. Even China is deeply linked to the U.S. and Europe through trade. The future lies with countries that are able to handle multiple alliances, seek strategic autonomy, and absorb shifting balances. Türkiye’s application to the SCO is not a turn to the East—it is an embrace of multidimensional diplomacy.

Conclusion

Türkiye’s move in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is not to be read either as symbolic or as a short-term tactical diplomatic maneuver but as a vision-based and necessity-driven strategic re-alignment. The SCO for Türkiye opens the door to break the limitations of the Western organizations, to design its own geopolitical identity and seek alliances on the grounds of respect and mutuality of interests. To the SCO, Türkiye presents the prospect of widening its civilizational reach, duplicating its functional role, and projecting itself as a true representative of a rising multipolar global order.

This is not a zero-sum game. Türkiye can and should become a hardline NATO member without losing its appetite for more interdependence with Eurasian institutions. Its history and geography push it toward such flexibility. This is not an issue of bloc loyalty, but being in the position of staying an independent player in an uncertain and increasingly fluid world.

In the coming years, as competition for world leadership intensifies and institutions change or crumble, the skill of moving between worlds will be the most important one. By consolidating its relationship with the SCO to an even greater extent, Türkiye is not only doing what is in its own strategic interest but also helping create a more balanced, inclusive, and realistic world order. It is a shift not away from the West, but toward a more common world of power, diverse identities, and multidirectional diplomacy.

Leave a Reply