The Anatomy of an Anti-Colonial Resistance

The Anatomy of an Anti-Colonial Resistance

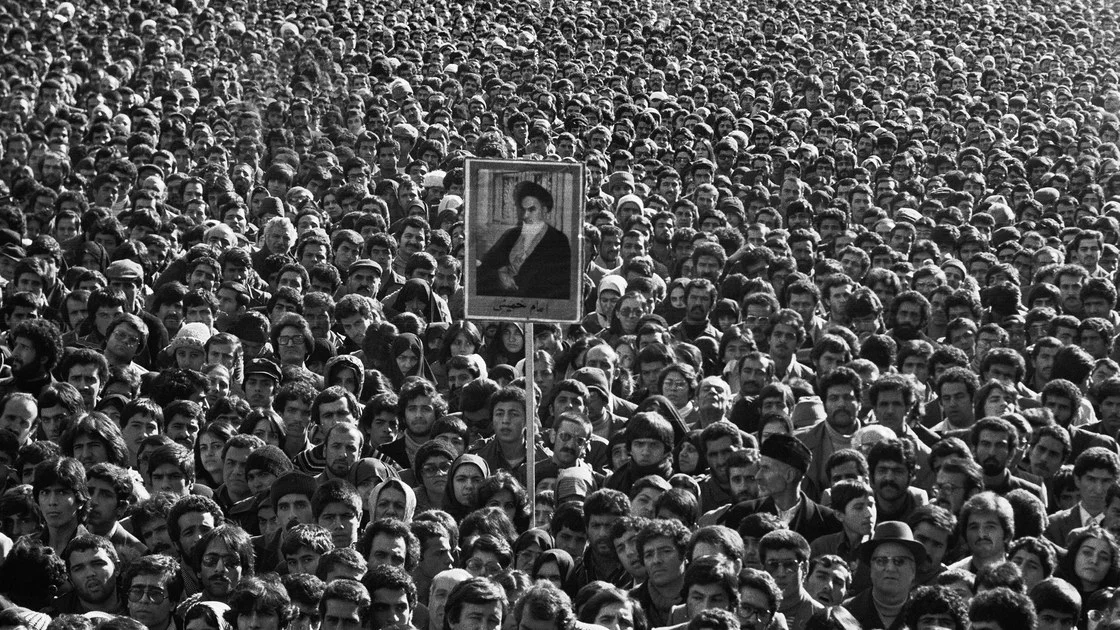

The Islamic Revolution of Iran is considered one of the most influential events at the end of the twentieth century, and like all historical events, it is open to various definitions. Immediately after the revolution, due to the approach adopted by the new ruling system in Tehran in its interaction with the West, the Western propaganda apparatus suddenly portrayed the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the emerging ruling system — the Islamic Republic — as a dangerous phenomenon that could jeopardize global security. In the atmosphere of propaganda by the world’s mainstream media, along with various attacks and immense political pressure exerted on the Iranian state and people, the essence of the Islamic Revolution, its historical foundations within Iranian history, and the impact this event had on the political dynamics of West Asia and the world were overlooked. In this context, the inability of the clerical establishment to provide a clear image of what it had in mind, along with the weakness of Iranian media, meant that the philosophy of the 1979 Revolution could not be presented as strongly as it had been at its inception.

Historical Background

The 1979 Islamic Revolution of Iran was in fact the outcome of all the experiences of the Iranian people since the beginning of the nineteenth century. After the collapse of the Safavid dynasty, Iran went through a century-long period of interregnum and lacked powerful governance. This situation was halted with the rise of the Qajar dynasty, a Turkic family which, like all Turkic dynasties, traced its legitimacy to Genghis Khan and had migrated to Iran from Anatolia. The Qajars managed to revive the Safavid-era Iran and restored the territorial integrity of Iran according to what had historically been recognized as Iranian territory. Although the Qajars were to some extent successful in restoring Iran’s territorial integrity after a long period of turmoil and fragmentation, they came to power at a highly inopportune historical moment. In the century preceding their rule, Iran had fallen into political instability and structural weakness. Concurrently with the beginning of Qajar rule, Europe was undergoing its greatest technological and industrial leap — a transformation that rapidly shifted the global balance of power in favor of Western countries. The Qajars and Iranian elites, however, neither possessed the necessary tools to understand these developments nor had the opportunity to keep pace with them. Iran’s first serious confrontation with this backwardness occurred during the long and exhausting wars with Tsarist Russia. These wars, which lasted over a decade, ended with the loss of the Caucasus — the most fertile and strategically vital part of Iranian territory. This bitter defeat abruptly exposed Iranians to the reality of the new global colonial order. At the same time, for some elites of that era, it marked the beginning of a reconsideration of the path toward modernization, reform, and escape from historical decline.

In this way, Iran entered a phase of striving for self-recovery in the modern world. Although the role of intellectuals and the position they held in introducing modern political discourses to the country has been frequently emphasized, one greatly overlooked point is the missing link between intellectuals and the people — namely, the religious scholars (ulama). At this juncture, the ulama in Iran, by emphasizing the necessity of empowering the country and preventing the domination of states such as Britain and Tsarist Russia, played a major role in mobilizing the general public and leading mass movements against colonialism. A particularly noteworthy point in this regard was the role of religious scholars in the economic sphere. In various cities, the ulama resisted Western colonial pressures and compelled the government not to surrender to such pressures, while at the same time stressing the importance of national production and the establishment of a national economy. One prominent example of the former is the Tobacco Protest Movement, in which the religious scholars, by issuing a ban on tobacco consumption, thwarted Britain’s economic colonization plans in Iran and prevented British companies from replicating their experience in India within Iran. As for the latter, the ulama themselves took initiatives such as establishing textile factories in an effort to promote domestic production and strengthen the national economy.

In the political realm as well, contrary to what is commonly propagated in official European historiography — which often depicts religion as an obstacle to modernity — it was the religious scholars who led the nation in establishing the constitutional system in Iran and forced the ruling authority to transition from absolute despotism to a parliamentary regime. Thus, from the second half of the nineteenth century and especially at the beginning of the twentieth century, the religious scholars, in addition to their spiritual and religious roles, also assumed political functions and played a major role in the anti-colonial struggle of the Iranian people.

Religious Scholars as Leaders of the National Front

With the rise of Pahlavi despotism in Iran, a period of regression in the democratic achievements of the Iranian people began. Despite the modernization of bureaucracy and technical sectors, Iranians lost democratic accomplishments such as an independent parliament and anti-colonial struggles. Thus, a period of estrangement between the nation and the state commenced. As a result of the Pahlavi dictatorship’s pressures, unlike the Constitutional Revolution era — when people actively participated in political life through local associations and various political movements — the populace was sidelined.

Consequently, while Iran during the Qajar period was in a much weaker state than at the end of Reza Shah Pahlavi’s reign, the people were able to resist colonial domination by Britain and Tsarist Russia and prevented especially the British occupation of Iranian lands — the role of Ayatollah Lari, one of the prominent clerics of southern Iran, and Rais Ali Delvari, a local fighter against the British army, is truly heroic. However, at the beginning of World War II, despite Iran being militarily much stronger than in the Qajar era, it was occupied by Britain and Russia.

The occupation of Iran by foreign forces, combined with the collapse of the oppressive dictatorship, and the infiltration of leftist revolutionary thought into the country, led to the beginning of a new phase in Iran’s intellectual and social life. During this period, anti-colonial thought and literature once again flourished through close cooperation between intellectuals and religious scholars and transformed into a nationwide discourse. The novels and stories from this period — written up until and shortly after the joint British-American coup of 1953 — are among the most important examples of anti-colonial literature in the world. Novels such as Neighbors and The Story of a City by Ahmad Mahmoud, Symphony of the Dead by Abbas Maroufi, Savushun by Simin Daneshvar, My Mother, Bibi Jan by Asghar Elahi, The Winds Announce the Change of Season by Jamal Mirsadeghi, Haji Agha by Sadegh Hedayat, as well as short stories by Sadegh Chubak, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, and others, are clear examples of anti-colonial tendencies among the Iranian masses.

During this period, the struggle to nationalize Iran’s oil industry and eliminate British economic colonialism — which had been imposed through the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company — became a central manifestation of the Iranian people’s anti-colonial movement. Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh and Ayatollah Kashani — who had previously fought against the British during World War I in Iraq — worked closely together to create one of the most brilliant chapters in Iran’s anti-colonial history, ultimately paving the way for the nationalization of Iranian oil. In this period, anti-colonial movements across the Middle East, with both Islamic and leftist tendencies, became one of the most powerful ideological and social currents. This environment laid the groundwork for revolutionary uprisings such as the Algerian people’s struggle against French colonialism and the rise of figures like Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt.

As a result of these serious and anti-colonial efforts, Britain and the United States orchestrated one of the most infamous coups in modern history — the overthrow of the legitimate government of Dr. Mossadegh in the coup known as Operation Ajax on August 19, 1953. To understand the roots of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, one must consider the severe blow suffered by the Iranian people following this coup and the return of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to power. This coup demonstrated that colonial powers were determined to suppress any popular movement and were committed to ensuring that only a puppet regime — one tasked solely with securing their interests — could govern Iran. From this point onward, particularly with the popularization of revolutionary leftist discourse among the masses and, on the other hand, with the politicization of Islamic identity — which had adopted anti-colonial and anti-despotic dimensions — the conditions for the February 1, 1979 Revolution were set.

The most important feature of this period was the formation of a global network of anti-colonial movements across the region and the world. Iran’s anti-colonial movements were influenced by global leftist movements as well as the political movements in the Arab world, which in turn helped strengthen their own position. As such, global developments had a major impact on how the Iranian people and elites perceived the actions of the Pahlavi regime. It was during this same period that, with the establishment of the Israeli regime on Palestinian land, both the leftist and Islamic currents within Iran’s anti-colonial movement turned their attention to the issue of Israel, and their activities began to extend beyond the borders of Iran.

To understand the transformations taking place in the minds of Iranian Muslim clerics during this period, attention must be paid to the book Shazrat al-Ma‘ārif (Shazrat al-Ma‘arif) by Ayatollah Shahabadi, as well as his other works. Ayatollah Shahabadi was the intellectual mentor of Ayatollah Khomeini, and he noticeably interwove discussions of Islamic knowledge (ma‘ārif) with subjects such as Western domination over Muslim lands and the role of economics in this matter.

The Historic Ashura Speech of 1963

To understand the roots of the Islamic Revolution of Iran and the perspective that the Islamic Republic later adopted toward the issue of Israel, the historic speech delivered by Ayatollah Khomeini on June 5, 1963, holds significant importance. On that day — which coincided with Ashura, the day of the martyrdom of Imam Husayn, the third Shiite Imam, at the hands of Yazid’s army in Karbala — Ayatollah Khomeini delivered a political sermon rather than the traditional Ashura speech, which typically recounts the sufferings of the Prophet’s family and the crimes of the Umayyad dynasty in distorting the true teachings of Islam.

In this speech, which is considered one of the most influential speeches in Iran’s modern history, he emphasized that he was a well-wisher of the Shah and that he hoped no situation would arise in which, if the Shah had to leave the country one day, the people would rejoice in his departure — just as they had celebrated his father’s expulsion from Iran. He then focused on the issue of national independence and the struggle against colonial powers and addressed the matter of Israel. Khomeini did not speak of Israel from a purely religious standpoint, but rather from the perspective of anti-colonial resistance and the role this regime could play in weakening Iran and the peoples of the Middle East.

Given the significance of this part of his speech, the exact words are quoted below:

“Israel does not want scholars to exist in this country. Israel does not want the Qur’an to exist in this country… At the invitation of its dark agents, Israel strikes us; it strikes the people. It seeks to seize your economy; it wants to destroy your agriculture and commerce; it wants this country to be devoid of wealth and to seize the riches through its agents. Anything that stands in its way, anything that acts as a barrier — it breaks these barriers. The Qur’an is a barrier; it must be broken… Our government, in obedience to Israel, insults us.”

Following this speech by Ayatollah Khomeini, the city of Qom and the religious seminary of Feyziyeh were attacked, effectively igniting the initial sparks of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Ayatollah Khomeini was arrested and faced the threat of execution. He was ultimately released as a result of simultaneous pressure from both religious scholars and various political groups.

However, sometime later, when the Iranian government accepted the Capitulation Law — which granted judicial immunity to American citizens in Iran — Ayatollah Khomeini regarded this development as a violation of Iran’s national sovereignty and inaugurated a new chapter in the anti-colonial struggle of the Iranian people. In a historic speech delivered on October 26, 1964, he launched his first direct attacks against the United States. This speech must be considered one of the most profoundly anti-colonial speeches in the history of the Middle East — one that led to a world-shaping uprising.

Stating that after the approval of the law granting judicial immunity to Americans in Iran, he experienced grief and cardiac distress, Khomeini explained the matter as follows:

“Our dignity was trampled; the greatness of Iran was destroyed; the greatness of the Iranian army was crushed. A law was passed in parliament granting all American military advisers — along with their families, technical staff, administrative employees, servants, and anyone associated with them — full immunity from any crimes they may commit in Iran! If an American servant, if an American cook, assassinates the highest-ranking religious scholar of yours in the middle of the marketplace, crushes him underfoot, the Iranian police are not allowed to intervene! Iranian courts are not permitted to prosecute or interrogate; the case must go to America! There in America, the masters will decide what is to be done!

This law was passed in parliament with the utmost shamelessness, and the government, likewise with shamelessness, supported this disgraceful act! They deemed the Iranian people inferior to American dogs. If someone were to run over an American dog, they would be prosecuted; but if the Shah of Iran were to run over an American dog, he would be held accountable. And if an American cook were to run over the Shah of Iran, or trample underfoot the highest religious authority in Iran — no one would have the right to object!”

In the continuation of his speech, he named Britain, the United States, and Israel as the principal agents of colonialism in Iran, emphasizing that their goal was to seize control of Iran’s economy and, subsequently, to destroy its independence. This speech by Ayatollah Khomeini had such a profound historical impact that it led to his second arrest and ultimately to his 15-year exile outside of Iran.

It was during this same period that anti-colonial thought in Iran entered a new phase with the emergence of the concept of Gharbzadegi (“Westoxification”) introduced by the prominent Iranian writer and intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad, which went on to influence the future course of the Iranian people’s political trajectory.

Contrary to what might initially come to mind, the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran did not emerge primarily in response to religious restrictions, the Pahlavi regime’s opposition to Islam, or the prohibition of religious practices. Rather, its true roots lay in the broader anti-colonial and anti-despotic struggles that had begun with the Constitutional Revolution and entered a new phase after the 1953 coup. This revolution was not a reactionary movement against modern Western civilization as a whole — whether as a cultural construct or a geographic reality — but a progressive revolution aimed at resisting colonial domination and the imperialist posture of the West, particularly as it manifested in Iran and across the Global South.

The Iranian Revolution represented a nation’s collective effort to secure its independence from the economic and political chains of American imperialism. This is why the central slogan of the 1979 Revolution was: “Independence, Freedom, Islamic Republic.” Aligned with this vision, shortly after the revolution’s success, international conferences were convened in Iran that brought together revolutionary and anti-colonial movements from Latin America to Africa and the Arab world. In essence, Iranian revolutionaries sought to present their revolution as a model for global liberation from colonial powers and to actively support other anti-colonial movements across the world.

The clearest expression of this ideal can be found in Ayatollah Khomeini’s speech on June 5, 1979, delivered on the anniversary of his pivotal June 5, 1963, speech — a moment that had catalyzed the revolutionary process. Having returned from 15 years of exile and led a largely nonviolent mass uprising, Khomeini declared:

“O Westoxicated ones! O foreign-worshippers! O hollow men! O people devoid of content! Wake up! Do not westernize everything you possess. Observe what exists in the West — the good things. Observe the human rights organizations in the West and ask yourselves: who are these people and what are their true objectives? Are they really concerned with human rights or with the rights of superpowers? They are servants of the superpowers and seek to safeguard their interests. You — our legal scholars and human rights advocates — do not follow in their path. Instead, look to the people, to the hardworking classes, and uphold justice yourselves. These laborers, these farmers — they are the real human rights advocates. They act, while you merely talk. None of you work to truly secure people’s rights. Those who act are the very ones who rose up today, just as they did sixteen years ago. They are the ones who truly care for humanity.”

Although the Islamic Revolution and the state that emerged from it — the Islamic Republic — have undergone many ups and downs, and though it failed to fully realize some of its ideals and in some cases even strayed from its founding principles, it undoubtedly succeeded in achieving its central aim: breaking the chains of colonial domination imposed on the Iranian nation. This is precisely why, just months after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Iran was attacked by Saddam Hussein’s regime — an assault widely understood as having been supported by the full force of Western powers. Following the eight-year war, Iran became subject to one of the harshest and most sustained economic, political, and media wars of the modern era. This included wide-ranging international sanctions that, in many cases, banned even the most basic forms of trade, prohibited the transfer of modern technology to Iran, restricted Iranian students’ access to top global universities, blocked Iranian radio and television networks from international satellites, and even included embargoes on essential medicine.

Despite some internal dissatisfaction — often the result of deviations from the original ideals of the revolution — the Iranian people have, for over 45 years, remained proud of the revolution’s core achievement: national independence. This sense of sovereign dignity remains the key to the endurance and resistance of the Iranian people amid the most extensive and aggressive Western sanctions regime in modern history.

Leave a Reply