The Brahmaputra and Indus no longer simply carry glacial melt and monsoon rain. They carry contested power, unresolved histories, and national ambitions in liquid form.

The Brahmaputra and Indus no longer simply carry glacial melt and monsoon rain. They carry contested power, unresolved histories, and national ambitions in liquid form.

By Dure Akram, from Lahore / Pakistan

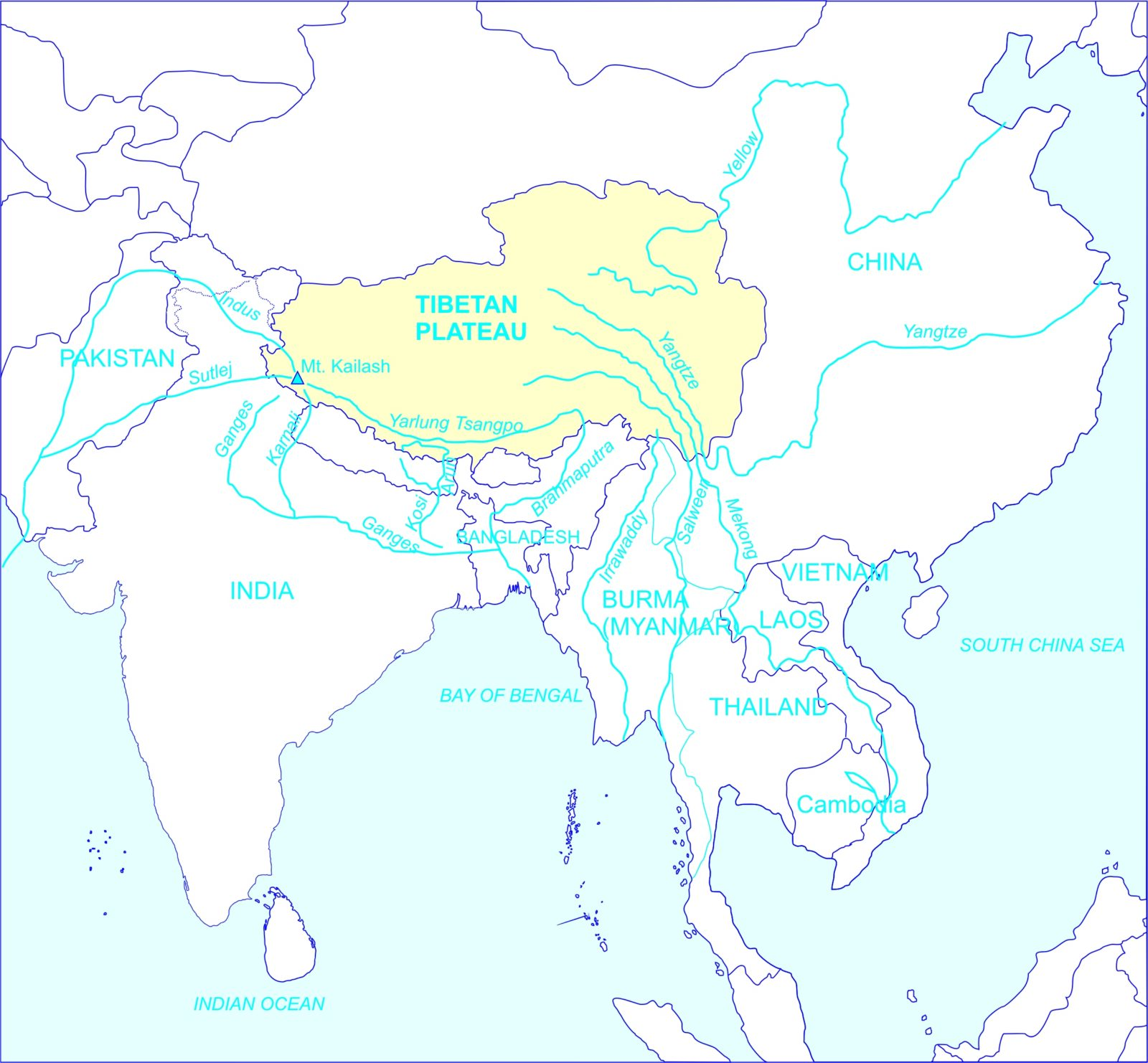

The Brahmaputra is no longer just a marvel of nature. It has become a fulcrum of geopolitical power. From its origin in the highlands of Tibet to the crowded deltas of Bangladesh, the river now moves not just water, but strategy, pressure, and consequence.

China has begun constructing the Medog (Motuo) hydropower project in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Premier Li Qiang has called it the “project of the century.” The facility is expected to produce close to 300 billion kilowatt-hours annually—nearly three times the output of the Three Gorges Dam. The project’s estimated cost exceeds 1.2 trillion yuan, and commercial operations are expected by the early 2030s.

Beijing describes the dam as an environmental solution, crucial to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. Chinese officials insist the project won’t affect downstream states and falls squarely within national borders. Its public aims include power generation and flood prevention. However, the true impact lies in its scale and strategic placement. Located at a dramatic bend in the river where it drops 2,000 meters in under 50 kilometers, the Medog project gives China unprecedented control over the flow into India and Bangladesh. Even without creating a massive reservoir, the structure can influence seasonal flow, turbidity, and sudden releases.

India has taken notice. Pema Khandu, Chief Minister of the northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, warned that the dam poses an “existential threat” and called it a “ticking water bomb.”

These concerns aren’t speculative. On the Mekong, independent monitors documented how Chinese dams restricted almost the entire wet-season flow in 2019, even though the upstream region had normal to above-average rainfall. This contributed to the drought in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. Beijing dismissed the findings, but the regional impact was undeniable. The pattern is now familiar: upstream engineering met with downstream hardship.

India’s conduct undermines its complaints. In April 2025, following a deadly attack in Kashmir, New Delhi suspended the Indus Waters Treaty (a pact signed with Pakistan in 1960) that had weathered wars and decades of hostility. Speaking after the decision, Home Minister Amit Shah was direct: “No, it will never be restored,” he said. “We will take water that was flowing to Pakistan to Rajasthan by constructing a canal. Pakistan will be starved of water that it has been getting unjustifiably.”

This was not diplomatic language. It was the open politicization of a shared natural resource.

Islamabad responded with clarity. Pakistan’s National Security Committee stated that any move to obstruct the flow of Indus water would be treated as an act of war. Senior officials echoed this message in every international forum available. Their concern is grounded in national survival: nearly 80% of Pakistan’s agriculture depends on the Indus River system. When control is concentrated upstream, alarm is inevitable.

Meanwhile, India rejected international arbitration on the Indus dispute and declared the treaty suspended. At the same time, it advanced its counter-project, the Siang Upper Multipurpose Dam in Arunachal Pradesh, marketed as a safeguard against Chinese water releases. Communities in the region have resisted. Indian geologists have warned that large dams in the eastern Himalayas could trigger seismic risks. But the plan is moving forward. The contradiction is stark: India criticizes unilateralism by others while building its own arsenal of hydraulic control.

Pakistan, in contrast, has turned to structured resilience. While India walked away from legal commitments, China fast-tracked the Mohmand Dam in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. That project will provide 800 megawatts of power, 300 million gallons of clean water daily for the city of Peshawar, and vital flood protection. Larger efforts like the Diamer-Bhasha Dam are also underway, addressing Pakistan’s dangerously low storage capacity. Going beyond symbolism and with each additional cubic meter stored, Pakistan intends to reduce its vulnerability to India’s manipulation.

Further downstream, Bangladesh faces a different kind of fragility. The Brahmaputra—known locally as the Jamuna—sustains more than half of the country’s agriculture. Its Foreign Affairs Adviser, Md Touhid Hossain, accepted China’s explanation that the Medog dam would not reduce water flow. But he acknowledged the deeper imbalance: “Our rivers do not originate in our territory. Structures have already been built upstream, and more will follow. We cannot stop them.” In a basin with no binding agreement, Bangladesh must rely on cooperation, data sharing, and goodwill—all of which can collapse under the weight of regional tensions.

The legal disparity across the region is sharp. The Indus basin had a comprehensive treaty, World Bank mediation, and a permanent bilateral commission. That still didn’t prevent India from unilaterally halting it. The Brahmaputra, on the other hand, has no formal agreement among riparian states. China is not party to the UN Watercourses Convention. There is no court, no mechanism, no arbiter. In this vacuum, control passes to those who can build, store, and release.

India’s suspension of the Indus treaty has removed its moral standing in the regional debate. Once the loudest voice demanding transparency from upstream states, it now operates with the same opacity it once condemned. Its position has shifted from defender of rules to agent of disruption. What it sees in China’s Brahmaputra strategy is now a mirror to its own.

China, meanwhile, holds the upstream advantage on the Brahmaputra. Its projects pose a direct challenge to India’s water security. India, in turn, occupies the upper hand on the Indus, holding Pakistan hostage to seasonal flows and timing. These two axes (Brahmaputra and Indus) are now locked in a new regional geometry of pressure and reprisal.

Pakistan’s response has been consistent. Rather than grandstanding, it has moved to build capacity, working with Chinese capital, Chinese engineers, and Chinese deadlines to restore control over its own future. At the same time, it has escalated its campaign to frame India’s suspension of the Indus treaty as a violation of international peace.

The stakes have already been spelt out in the words of leaders. “Any attempt to divert or stop water meant for Pakistan … will be considered an act of war,” Islamabad stated. “No, it will never be restored,” said Amit Shah, when asked about the future of the treaty. “Project of the century,” Li Qiang declared. “A ticking water bomb,” warned Pema Khandu.

All of these are positions. And they are being executed in a climate-stressed, flood-prone region that holds three nuclear powers.

The Brahmaputra and Indus no longer simply carry glacial melt and monsoon rain. They carry contested power, unresolved histories, and national ambitions in liquid form.

Pakistan now has a strategic imperative: to treat every new dam as a national security asset, every megawatt of hydropower as leverage, every additional day of storage as insurance against coercion. The diplomacy must be backed by engineering. The rhetoric must be underwritten by readiness.

In this region, sovereignty is measured by how much water a state can control and how little it can afford to lose.

Leave a Reply