This is the global motto for the 21st century.

This is the global motto for the 21st century.

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

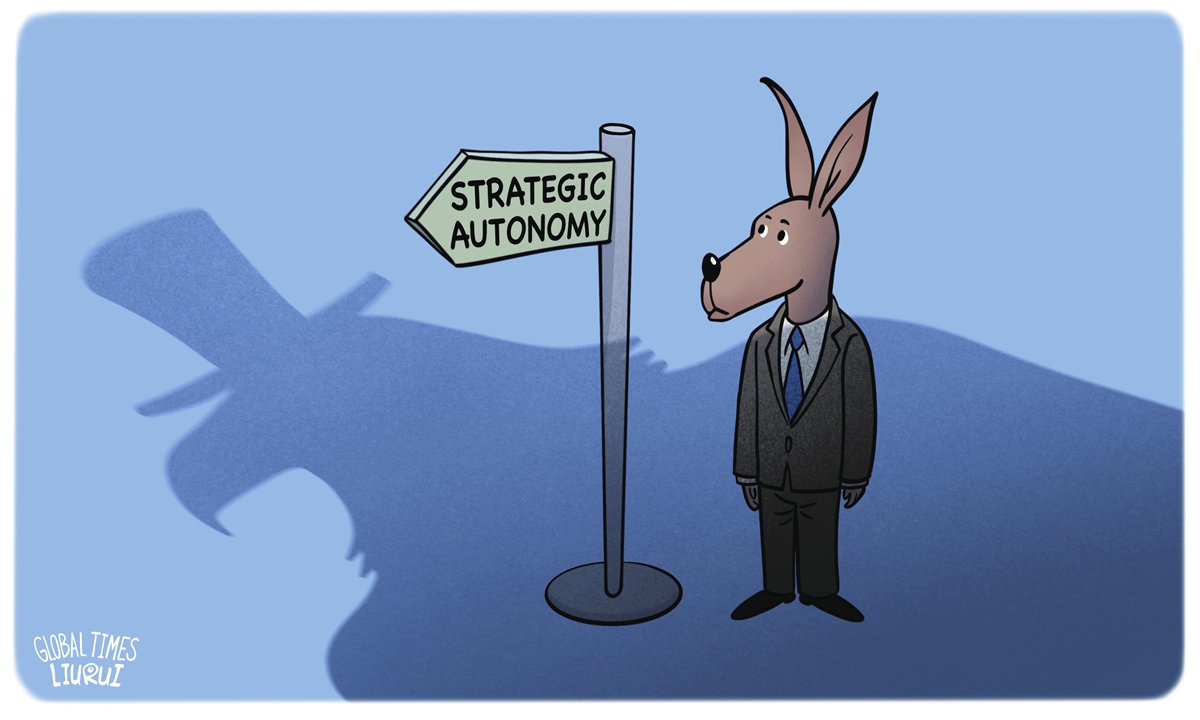

Australia has always cast its defense strategy in the mold of the alliance model. Canberra has worked under the assumption since the ANZUS Treaty signing in 1951 that its security interests are best aligned closely with the United States. This has shaped its procurement decisions, military training, intelligence cooperation, and diplomatic stance for over seventy years. But as the geopolitical order changes rapidly and uncomfortably, the question is more urgent than ever: can Australia indefinitely bank on American power, or is it time to chart a path towards genuine strategic autonomy?

The answer is not merely academic. As U.S.-Chinese competition escalates, American politics becomes more unpredictable, and regional dangers mutate, Australia’s security calculus has to mutate as well. The idea of “strategic autonomy” has been dismissed in Canberra for years as a European vanity or unrealistic indulgence. But increasingly, it’s apparent that autonomy—not isolationism, but capacity and freedom to decide—are a necessity, not an indulgence.

The risks of over-reliance on the United States are no longer hypothetical. The Trump presidency and indeed the possibility of a new administration with similar inclinations has cast long shadows on America’s credibility as a partner. Washington’s strategic priorities can shift abruptly on the basis of domestic political cycles, internal polarization, or global overextension. The assumption of American security guarantees, once taken for granted, now needs to be revisited—not because the alliance is flawed, but because the world that made it possible no longer exists. Australia needs to ready itself for the possibility that the U.S. will be a less committed or less dependable ally in the coming years.

More specifically is the danger that Australia’s default synchronization with U.S. war planning may draw it into wars not within its national interest. The AUKUS agreement, offering the promise of high-end submarine capability and defense technologies, also binds Australia more firmly to American strategic interests—particularly in relation to China. This alignment threatens to limit Australia’s diplomatic space in the Indo-Pacific, where every nation wishes to hedge, not bet, between Beijing and Washington. Strategic autonomy in this case is more about not pushing the U.S. away but ensuring that Canberra has the sovereign capacity to make its own threat assessments and responses.

What would independence in these terms look like in practice? It would have to be invested in beforehand in local defense industry capability. Australia can no longer rely so heavily on foreign procurement of major platforms, ammunition, and surveillance systems. Local development of particular technologies—cyber defense, missile production, and sea protection—would reduce dependence and enhance national resilience. This is not a case for self-sufficiency in all things, but selective self-reliance in the most vulnerable to disruption or political coercion.

Second, Australia must build a more diverse range of regional defense partnerships. The alliance with the U.S. will remain a foundation, but deeper cooperation with Japan, India, Indonesia, South Korea, and Pacific Island nations would increase Australia’s strategic depth. The partnerships must extend beyond joint military exercises to intelligence sharing, joint innovation, and defense co-production. A security network embedded within the region—multilateral, inclusive, and multipolar—would complement, not substitute for, traditional alliances.

Third, Australia should develop a defense doctrine clearly attached to national and regional, rather than international ideological, interests. Strategic independence is not a rejection of liberal democratic values—but the ability to secure such values through independent power. An independent Australia would be best positioned to be of use for regional stability, to contribute to humanitarian intervention, and to resist coercion without over-enforcement in distant power contestation.

This shift in attitude would also add to the diplomatic heft of Australia. A country that is seen to be capable of looking after itself—and is willing to stand on its own principles—elicits more respect in Washington and Beijing. Independence is credible; it shows that alliance is a choice, not a dependence. It allows Australia to be a stakeholder in Indo-Pacific security, not merely a reactor to the actions of others.

Of course, this change would not come cost-free. Strategic autonomy will demand long-term investment, political consensus, and cultural transformation in the defense bureaucracy. It will involve uncomfortable discussion of trade-offs, such as the limitations of alliance loyalty and the price of sovereign capability. But avoiding such investments would be far more costly in the long run—both in strategic flexibility and national prestige.

Conclusion

Australia’s security strategy must move beyond inherited assumptions. The 20th-century approach—based on distance, alliance, and deference—will not suit a 21st-century world of proximity, competition, and uncertainty. The time has come for Canberra to place strategic autonomy at the heart of its defense strategy—not as a repudiation of the U.S. alliance, but as a recognition of its limits.

Genuine autonomy is not a one-sided action. It is the power, wisdom, and ability to decide when, how, and why to act. It is planning for the contingency that alliance support may collapse or change. Furthermore, it is being able to say “yes” or “no” on the basis of strength, not coercion. And above all, it is establishing a defense posture on the basis of national interest, regional responsibility, and sovereign dignity.

Should Australia go down this path, it can emerge as not just a better ally, but an independent leader, one capable of influencing from within a stable, resilient Indo-Pacific order, one that is no longer underpinned by America’s power but by this region’s internal dynamics and stability. Strategic autonomy is not a gamble. In this age, it is the surest wager on durable security and sensible statecraft.

Cover graph by Global Times.

Leave a Reply