Progress on De-Dollarization and infrastructure, while some contradictions, especially in Brazilian foreign policy continue.

Progress on De-Dollarization and infrastructure, while some contradictions, especially in Brazilian foreign policy continue.

By Fernando Esteche, from Buenos Aires / Argentina

The 17th BRICS Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro, marks a turning point in the reconfiguration of the global order. Beyond the headlines of notable absences and diplomatic declarations, the agreements reached reveal both the bloc’s transformative potential and its internal contradictions, especially in a context where Western hegemony faces unprecedented structural challenges.

Xi Jinping’s absence for the first time since 2012 and Putin’s virtual participation should not be interpreted as weakness, but rather as a repositioning strategy. China, focused on its strategic competition with the United States and the development of the Belt and Road Initiative, operates from a functional logic that transcends ceremonial summits. Its presence materialized in concrete agreements: the New Development Bank maintains its headquarters in Shanghai, and intra-BRICS trade flows continue to gravitate around its economy.

This apparent physical absence masks a deeper strategic presence. The Asian giant has chosen to consolidate its influence through tangible economic instruments rather than political declarations, an approach that could prove more effective in the long term.

Strengthening the New Development Bank and de-Dollarization

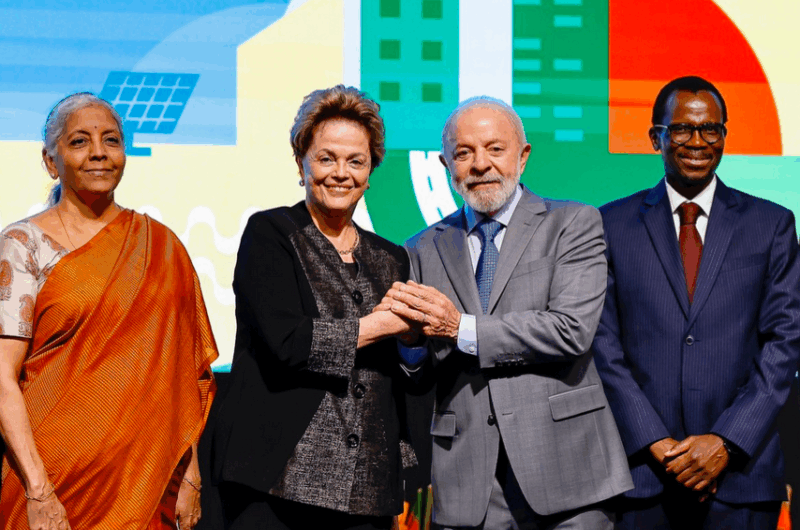

The meeting between Lula and Dilma Rousseff, president of the NDB, celebrated the progress of the “BRICS Bank,” consolidating an institution that has disbursed more than $35 billion in sustainable infrastructure projects. The NDB announces its focus on financing infrastructure projects, including water distribution systems and renewable energy, positioning itself as a real alternative to World Bank conditionalities.

The strategic importance of this institution lies in its ability to offer financing without the traditional political conditions of the Bretton Woods system. With initial capital of $100 billion, the NDB represents the most concrete embodiment of an alternative financial architecture.

The NDB has committed to allocating 40% of its disbursements to climate change-related projects.

The bloc condemned the tariff increase and expressed concerns about the disruptions to global trade caused by the tariffs, which should be read as a direct response to the Trump administration’s trade policies. This statement accompanies concrete progress in the use of national currencies for bilateral trade, especially between Russia, China, India, and Brazil.

Bilateral swap agreements have expanded significantly. Russia and China now process more than 95% of their bilateral trade in local currencies, while India has established similar mechanisms with several BRICS partners. Brazil, although more cautious, has increased its transactions in Reais with BRICS partners.

The Santos-Chancay Bi-Oceanic Railway Corridor: The Logistics Revolution of the South

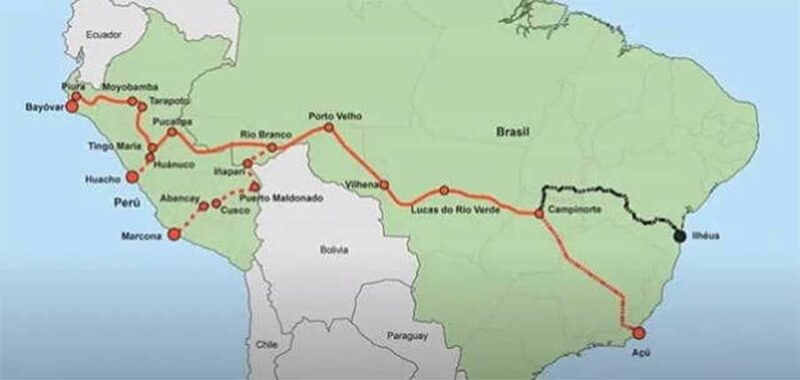

The most transformative element discussed, although not on the central agenda, was the consolidation of the Bi-oceanic Integration Railway Corridor, which will connect the port of Santos (Brazil) with the megaport of Chancay (Peru). The corridor allows western Chinese cities like Chongqing to avoid more congested traditional routes by combining rail and sea transport.

This infrastructure represents much more than a trade route: it constitutes a geopolitical revolution that breaks South America’s historical dependence on Atlantic routes controlled by traditional powers. The railway would begin in the Brazilian cities of Porto Velho and Cruzeiro do Sul, extending into Peruvian territory as far as Pucallpa, ultimately connecting Santos with Chancay, thus linking Brazil’s industrial heartland with the Asia-Pacific region.

The Port of Chancay, developed with Chinese investment, is emerging as the most important logistics hub in the South American Pacific. Its capacity to handle deep-draft vessels and its direct connection to the continental rail network promise to reduce transit times between Asia and Brazil from 35 to 23 days.

This corridor constitutes a lethal wound to the foreign trade hegemony that the West imposes on the South American subregion.

Brazilian Contradictions: Between Leadership and Dependence

Brazil’s position embodies the tensions of the Global South between autonomy and subordination. While Lula presents himself as a spokesperson for emerging countries, his proposals reveal a mentality still trapped in the logic of recognition within the existing system.

The proposed reform of the UN Security Council, removing veto power but including Japan and Germany as permanent members, would paradoxically strengthen the Western majority. Far from challenging the legitimacy of the Council as a neocolonial instrument, and rather than highlighting its customary impotence, Brazil seeks to join it, revealing a diplomacy that prioritizes symbolic advancement over structural transformation.

Similarly, Brazil’s proposal for “links of articulation and dialogue” with the G7 responds more to a logic of “balancing blocks” than to a strategy of building autonomous power. This ambivalence weakens the transformative potential of the BRICS and generates internal tensions with partners who prioritize confrontation with the unipolar order. Itamaraty’s entrenched diplomatic logic seems anachronistic in a reality where the rules-based order no longer exists.

The invitation to Cuba had a symbolic value that transcends ceremonial diplomacy. It represents the recognition that building a multipolar order requires incorporating countries historically marginalized from the international system. Cuba’s presence sends a clear message: BRICS is not just a club of emerging economies, but a platform for resistance against unilateral sanctions and financial blackmail.

Potentials and Limitations: A Critical Balance

Among the emerging strengths worth highlighting are the institutionalization of a new financial aid and support scheme; the NDB, which demonstrates that it is possible to build efficient and operational alternative financial institutions; the practical de-Dollarization through trade agreements in local currencies, which are gradually eroding the dollar’s hegemony; South-South connectivity; with logistics corridors like Brazil-Chancay, which are redefining global trade flows; and the bloc’s growing legitimacy as a possible space for contention; the previous accession of countries such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates expands the bloc’s representativeness, and the different forms of association grant it flexibility and the capacity to absorb demands.

As structural limitations, we must note the heterogeneity of interests; different national strategies with multiple geopolitical alignments and tensions within the bloc itself complicate political coordination. Technological dependence, where most of the BRICS countries maintain critical dependencies in strategic technological sectors, is a factor. Geopolitical pressure resulting from the intensification of competition between China and the United States generates internal tensions. Diplomatic ambivalences, positions like Brazil’s, weaken the bloc’s coherence.

The Rio summit demonstrates that the BRICS are at a critical moment of transition. The central question is not whether the bloc can challenge the unipolar order, but whether it will be able to transcend internal contradictions and build a coherent alternative.

The Santos-Chancay corridor emerges as a symbol of this potential transformation. Its implementation would not only revolutionize continental logistics but also demonstrate the Global South’s capacity to build autonomous strategic infrastructures. In a world where whoever controls the routes controls the future, the consolidation of bi-oceanic corridors driven by the South marks a true geopolitical turning point.

However, this potential will only be realized if the BRICS countries manage to overcome the temptations of elegant subordination and embrace the construction of autonomous power. Latin America, in particular, must decide whether it will be a leading player or a passive stage in the struggle for the new world order.

The Rio summit did not resolve these tensions, but it did highlight them. In the coming years, the BRICS’ ability to contribute to effectively institutionalizing multipolarity will determine whether we are witnessing the birth of a new global order or simply the reorganization of the existing one under new forms of hegemony.

The future of the Global South depends on its ability to move from resistance to construction, from critiquing the Western order to create viable and attractive alternatives. In this transition, each summit is both an opportunity and a test of fire.

Leave a Reply