Revolutionary Failure and Political Realignment

Revolutionary Failure and Political Realignment

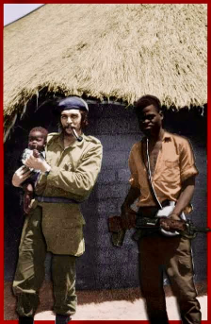

The iconic image of Che Guevara, cigar in mouth and eyes burning with revolutionary fervor, is typically associated with Latin America. However, in 1965, the Argentine revolutionary found himself deep in the jungles of Central Africa, attempting to ignite an anti-imperialist uprising in the newly independent but unstable Democratic Republic of the Congo. This little-known episode, documented in The Congo Diary, offers a unique lens through which to evaluate Guevara’s revolutionary praxis beyond the romanticism of Cuba and the tragedy of Bolivia. The Congo campaign represents the moment when the revolution was most starkly tested—and ultimately defeated—not by superior arms alone, but by internal contradictions, cultural disconnects, and unprepared leadership.

In the wake of Patrice Lumumba’s assassination in 1961, the Congo became a symbol of postcolonial betrayal and neocolonial interference. By 1964, multiple rebel groups were vying for control of the country, most notably the Simba rebellion, which attracted the attention of leftist movements globally. The Cuban government, committed to exporting revolution and countering imperialist influence, saw the Congo as a strategic front. Che Guevara, fresh from his role as Minister of Industry in Havana and restless for renewed militant engagement, volunteered to lead a contingent of Cuban advisors to assist the Simbas.

The Mission and its Objectives

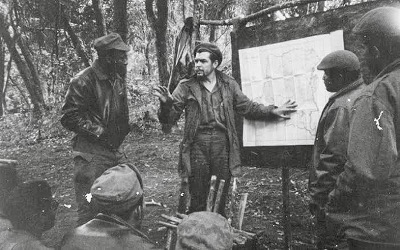

Guevara’s goals in the Congo were both ideological and practical. He aimed to provide military training and organizational structure to the Simbas; forge a Pan-African revolutionary alliance and create a model insurgency that could radiate into southern Africa, particularly Angola and Mozambique. However, from the outset, the mission was marred by logistical disarray, lack of cohesion among Congolese rebels, language barriers, and Guevara’s increasing disillusionment with local leadership. His diary entries reflect growing frustration with what he saw as undisciplined and opportunistic rebel commanders, who lacked both the ideological commitment and the military resolve that he had witnessed in Cuba.

The Congo Diary is not only a record of events but also a deeply introspective document. Guevara’s tone is often critical, not just of his allies, but of himself. He admits to strategic misjudgments and acknowledges the failure of transplanting the Cuban guerrilla warfare model onto a vastly different African terrain. Notably, he writes:

“We cannot liberate those who do not wish to fight for their own freedom.”

This quote encapsulates one of the central realizations of his Congo experience: that revolutionary change cannot be externally imposed. He also critiques the Cuban contingent’s own failings, including poor preparation, cultural insensitivity, and insufficient intelligence.

Che’s experience in the Congo also exposed him to the layered dynamics of race and identity in African liberation struggles. As a white Latin American in a Black African context, his presence was both a symbol of solidarity and a source of tension. Guevara was acutely aware of this and grappled with the limitations of his position. The campaign thus revealed not only political and logistical limits, but also the broader ideological challenge of forging transnational revolutionary alliances in postcolonial contexts.

Failure as Pedagogy

This article explores the rarely discussed African chapter of Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s revolutionary career: his 1965 mission to the Democratic Republic of Congo. Drawing primarily from his posthumously published Congo Diary (Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria: Congo), the article examines Guevara’s motivations, the operational dynamics of his failed campaign, and the ideological and strategic lessons he derived from this experience. The Congo campaign, though militarily unsuccessful, served as a crucial turning point in Guevara’s worldview, challenging his belief in the universality of the Cuban revolutionary model and confronting him with the complexities of postcolonial African politics.

Though militarily a failure, the Congo campaign became a crucible for Che Guevara’s revolutionary thought. It forced a reevaluation of strategy, ideology, and internationalism. His subsequent Bolivian campaign—while also ending in defeat—was more self-reliant and ideologically focused, partly shaped by the lessons of the Congo.

The Congo episode demonstrates that revolutionary movements cannot simply be exported; they must emerge organically from local conditions, leadership, and history. Che’s defeat in Africa was not just a military setback—it was a philosophical and pedagogical moment that challenged the universality of the Cuban revolutionary model and underscored the complexity of liberation in the Global South.

His Death and Legacy

About 30 minutes before Guevara was executed, American spy Félix Rodríguez* attempted to interrogate him regarding the whereabouts of other guerrilla fighters who were still at large, but Guevara remained silent. With the help of several Bolivian soldiers, Rodríguez assisted Guevara in standing up and led him outside the hut, parading him before the other Bolivian troops. He then informed Guevara that he would be executed. Shortly afterward, one of the Bolivian soldiers guarding Guevara asked him whether he was thinking about his own immortality. He replied, “No, I’m thinking about the immortality of the revolution.”

A few minutes later, Sergeant Terán entered the hut to shoot him. At that moment, Guevara reportedly stood up and addressed him with his final words: “I know you’ve come to kill me. Shoot, coward! You are only going to kill a man!” Terán hesitated, then pointed his semi-automatic M2 carbine at Guevara and opened fire, hitting him in the arms and legs. As Guevara writhed on the ground, apparently biting one of his wrists to keep from screaming, Terán fired again, delivering the fatal shot to Guevara’s chest. According to Rodríguez, Guevara was declared dead at 1:10 p.m. local time. In total, Guevara was shot nine times by Terán: five times in the legs, once in the right shoulder and arm, once in the chest, and once in the throat.

Months earlier, during his last public statement at the Tricontinental Conference, Guevara had figuratively written his own epitaph, saying:

“Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, if our battle cry has reached even one receptive ear and another hand stretches out to take up our arms.”

Though Che Guevara died in a small Bolivian village with few followers, his death amplified his influence far beyond what he achieved in life. For some, he remains a hero of resistance and anti-imperialist struggle. For others, a flawed revolutionary whose idealism clashed with geopolitical realities. Regardless, his impact is undeniable, making him one of the most enduring political icons of the 20th century.

References

Guevara, E. (2001). The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo (A. Wright, Trans.). Grove Press.

Anderson, J. L. (1997). Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. Grove Press.

Njoku, R. C. (2013). The History of Nigeria. Greenwood.

Gleijeses, P. (2002). Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976. University of North Carolina Press.

Vail, L. (Ed.). (1989). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press.

*Félix I. Rodríguez Mendigutia is a former CIA agent known for his involvement in the Bay of Pigs Invasion, his role in the interrogation and execution of Che Guevara, and his connections with George H. W. Bush during the Iran–Contra Affair.

Leave a Reply