Rule of Law or Geopolitical Rorschach Test

Rule of Law or Geopolitical Rorschach Test

By Mehmet Enes Beşer

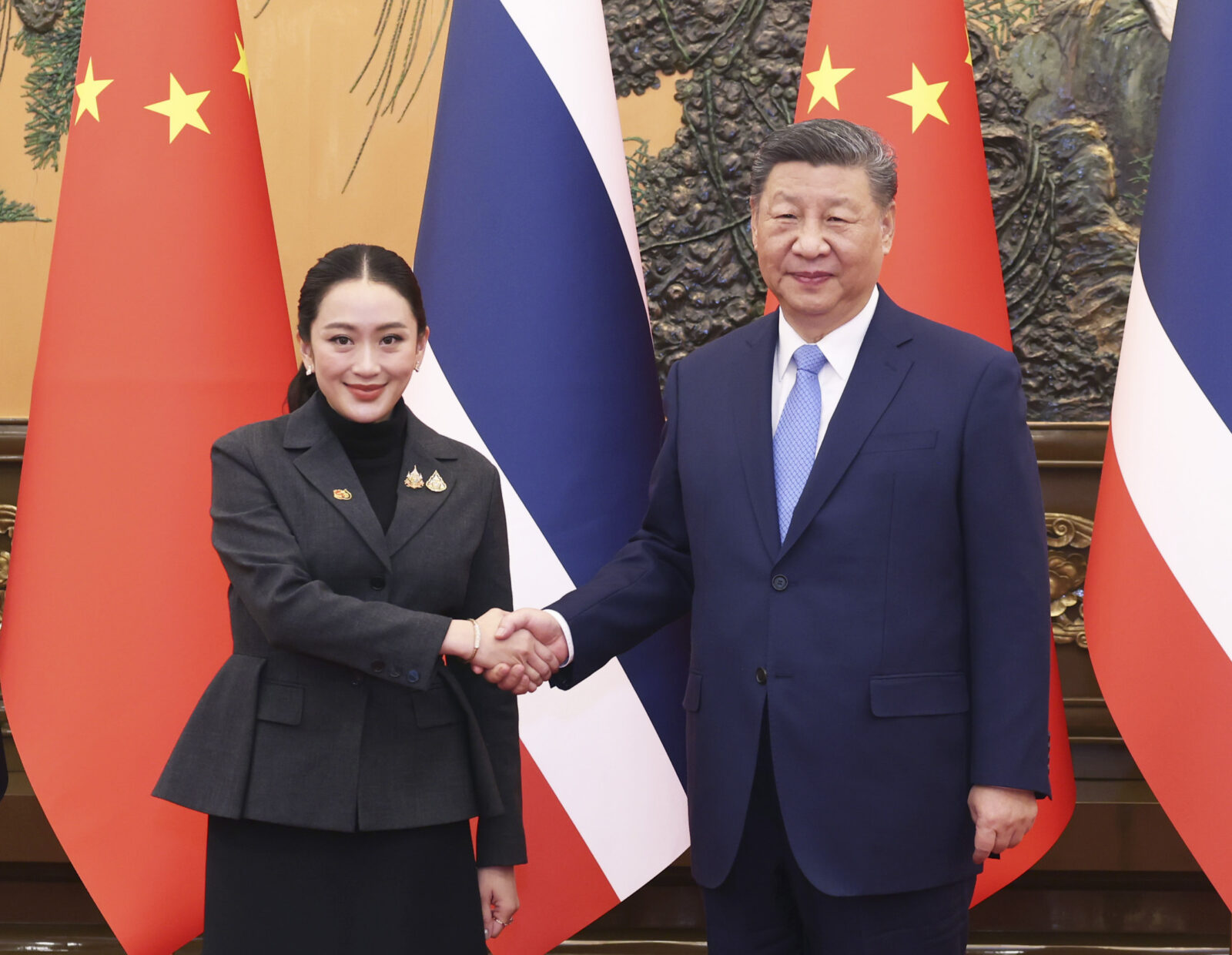

The recent forced repatriation of 40 Chinese nationals from Thailand—more than a decade after entering a state of legal limbo—should have been viewed as a case of overdue humanitarian closure and successful international coordination. Instead, it became one more hot-button issue in increasingly binary geostrategic discourse. The West, and particularly Washington, quickly described the operation as a “forced repatriation” of ethnic Uigurs, prompting accusations of human rights violations, religious persecution, and Beijing’s alleged coercion of regional allies.

But this incident is more than just another US-China competition news story—it is a revealing test case for three new tensions in the world: the meaning of rule-based cooperation, the erosion of multilateral trust, and the weaponization of human rights language. At its heart is a foundational question: when are legal actions by sovereign states human rights abuses, and who decides it?

Legitimate Repatriation or Political Provocation?

According to official Beijing as well as Bangkok reports, the individuals repatriated were illegal immigrants who crossed into Thailand a decade ago. The majority were deceived by criminal gangs and stranded in detention camps for years. Repatriation was affected under bilateral legal processes, involved direct pleas by relatives, and even humanitarian waivers for the sick.

By global norms, this is a classic case of bilateral law enforcement—a one based on the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, to which Thailand and China are both signatories. The operation, then, was not some covert rendition, but a result of cautious, coordinated diplomacy through the law.

But the Western response, led by American authorities and repeated by some NGOs, has been swift and condemnatory. The men, it was claimed—without much truth—were all Uyghur refugees and would likely be persecuted if repatriated. The narrative quickly moved from immigration management to political repression, with no room for subtlety or fact-checking.

The Double Standard Dilemma

What is so striking in this case is not only the criticism of China and Thailand, but also the silence regarding comparable—and often worse—practices in Western countries.

The United States, for instance, operates the world’s largest immigration detention system. Its enforcement techniques have included chaining deportees, holding children in overcrowded facilities, and exercising violence at borders. Custodial fatalities and separations of families have been chronicled by international and domestic watchdogs. These system-wide issues are rarely designated “human rights crises” on the same moral terms applied to other nations, though.

This inconsistency is not lost on the global South. Increasingly, Asian, African, and Latin American states perceive Western human rights attacks as politically driven rather than principled concerns. This undermines the moral credibility of global human rights activism and perpetuates the drift toward what can be called “sovereignty-based diplomacy”—where states prefer regional affinity and legal reciprocity over external pressure.

Southeast Asia’s Quiet Assertiveness

Thailand’s reserved response to U.S. criticism reflects a broader trend in Southeast Asia: insistence on independent decision-making in the face of external bluffing. Both a long-time U.S. treaty ally and a close economic friend of China, Thailand is the region’s “hedging” strategy—balancing great powers without surrendering to either.

This Chinese police collaboration with the West is by no means an indication of subservience, as some in the West have suggested, but an extension of regional autonomy. Cross-border crimes—phone scams, people smuggling, and unlawful immigration—are now a cost to be shared within Southeast Asia. This same bilateral collaboration between the Thai and Chinese governments has led to disbanding crime rings and, ultimately, bringing long-awaited relief to target populations.

The China-Thailand repatriation, therefore, must be understood in this regional context: as an input to an evolving process of building effective, rule-based security arrangements—not a piece in grand games.

The Global Narrative War

Ultimately, this is not as much about the fate of 40 people as it is about the struggle for who gets to set the agenda on international behavior. In today’s splintered information environment, facts are less important than narrative. A legal immigration operation becomes a human rights crisis, and decades of regional cooperation are overwhelmed by one accusatory headline.

If international law is to mean something, it must mean the same everywhere. If human rights are to be protected, they must be defended on the basis of standards applied consistently—not used for geostrategic purposes. And if multilateralism is to survive, it must be based on mutual respect—not selective moral outrage.

Conclusion: Toward Responsible Global Engagement

The China-Thailand cooperation on the matter—whatever its sensitivity—was procedurally openly and according to international law. It is maybe not optimal, but it is far preferable to selective enforcement, privatized detention, and crisis-level humanitarian failure elsewhere.

Rather than condemning China and Thailand, the incident should call for a greater debate about how nations can best address cross-border crime and irregular migration in a time of mounting displacement. It should also prompt the international community to develop more balanced and depoliticized human rights strategies based on evidence, not fear.

The world does not need more posing. It requires realistic cooperation, even in controversial issues. And if such cooperation can be underpinned by law, by compassion, by transparency—as it appears this repatriation was—then it is worth more than reflex condemnation. It is worth serious reflection and, indeed, a degree of respect.

Leave a Reply